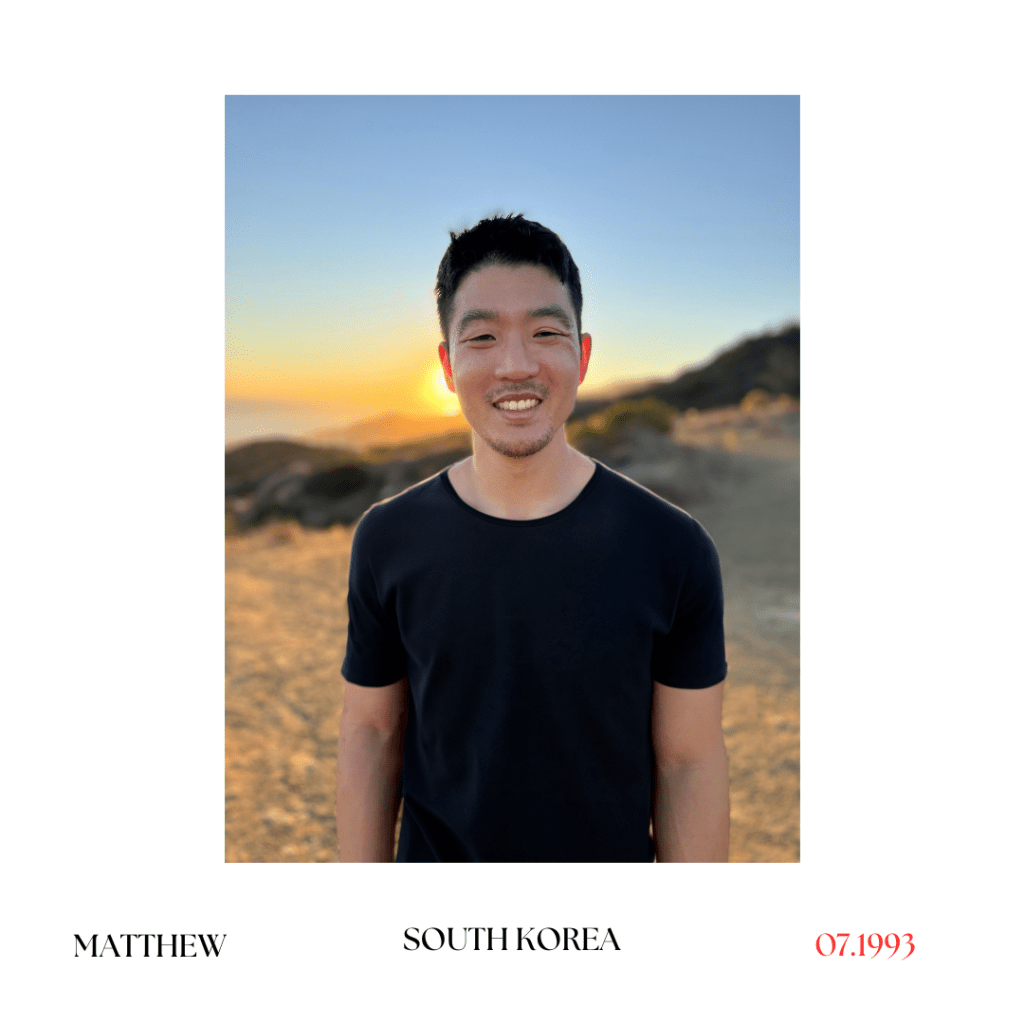

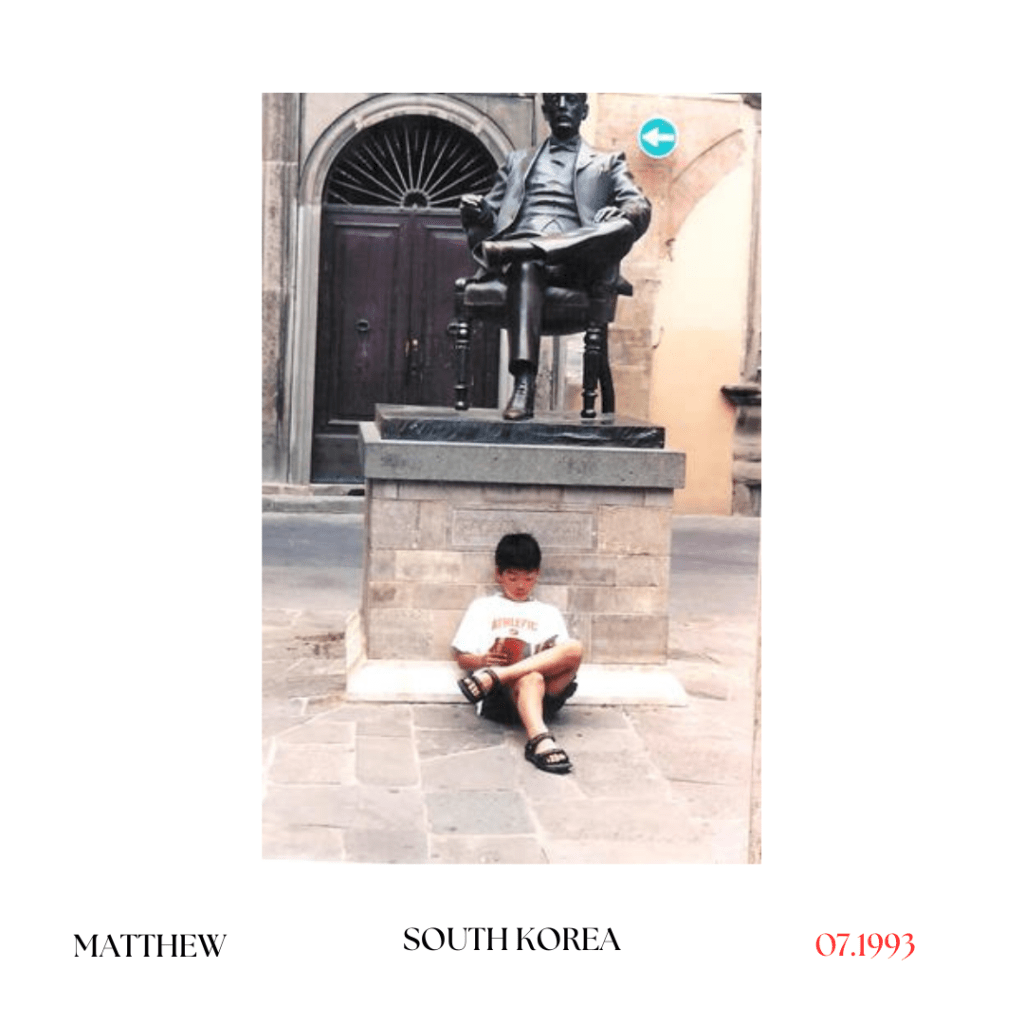

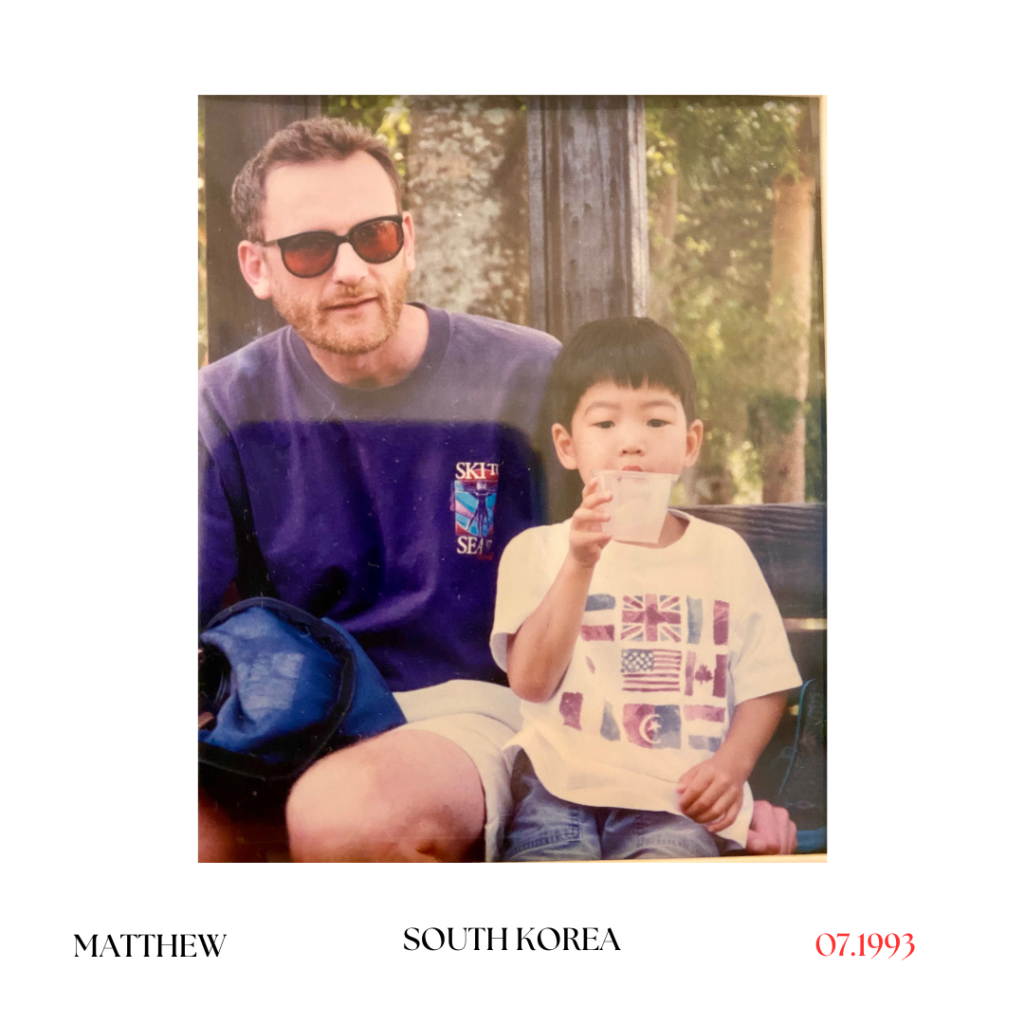

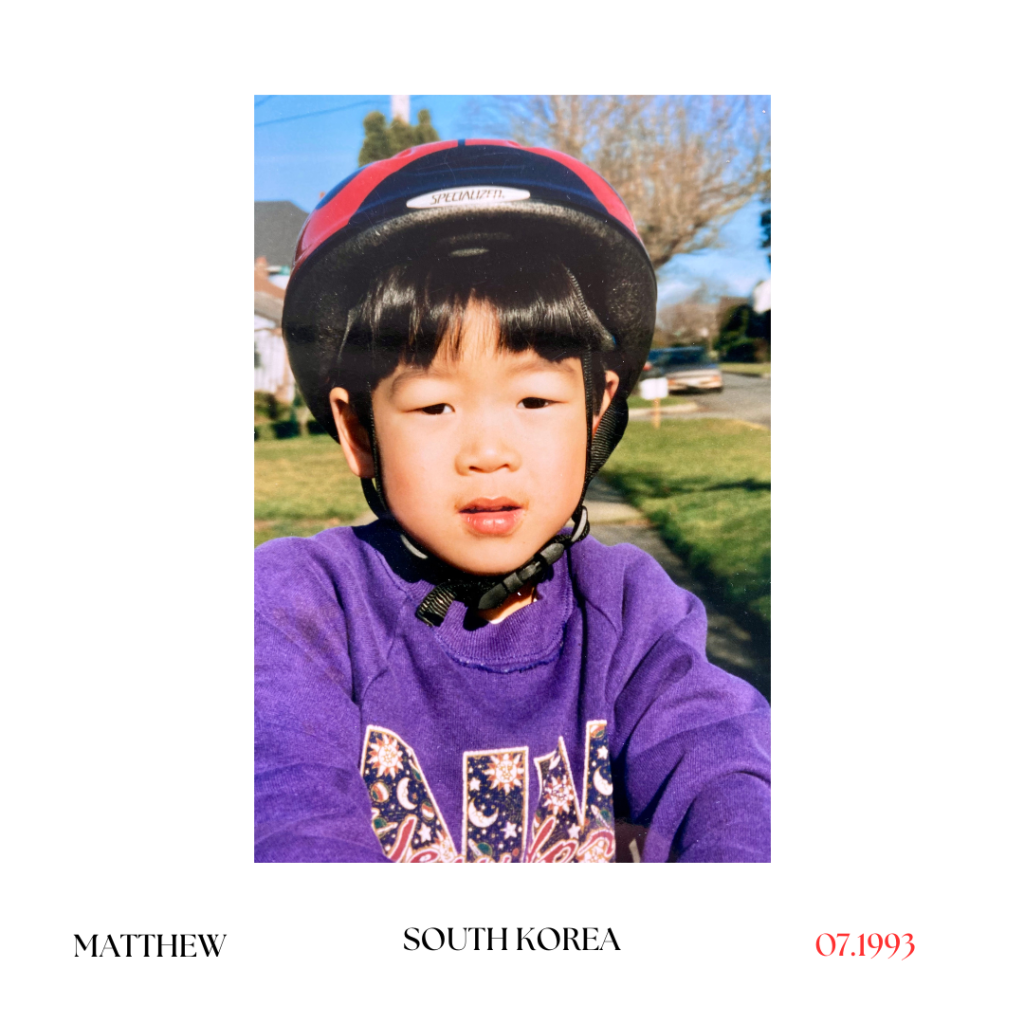

My name is Matthew, and I grew up north of Seattle in a city called Bellingham in the Pacific Northwest. I was adopted from Korea when I was six months old, but I was born in Seoul.

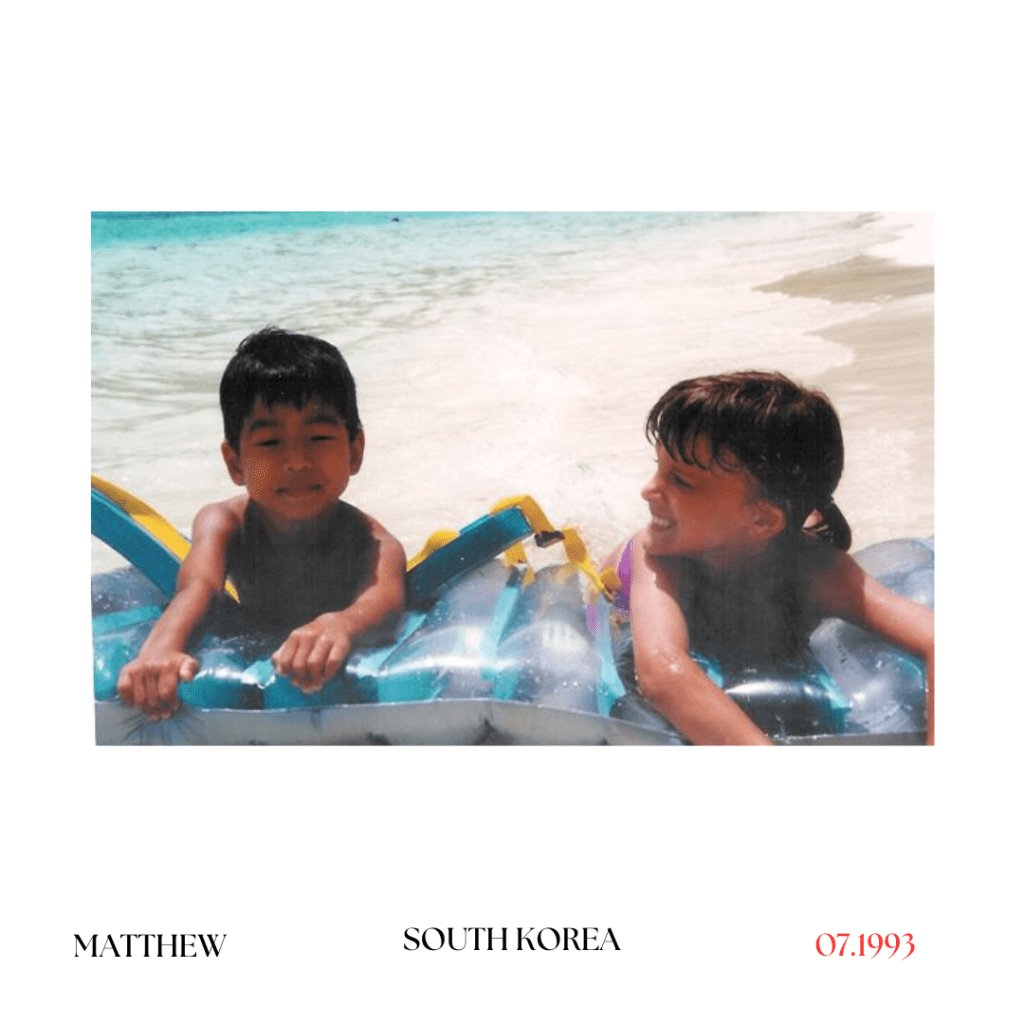

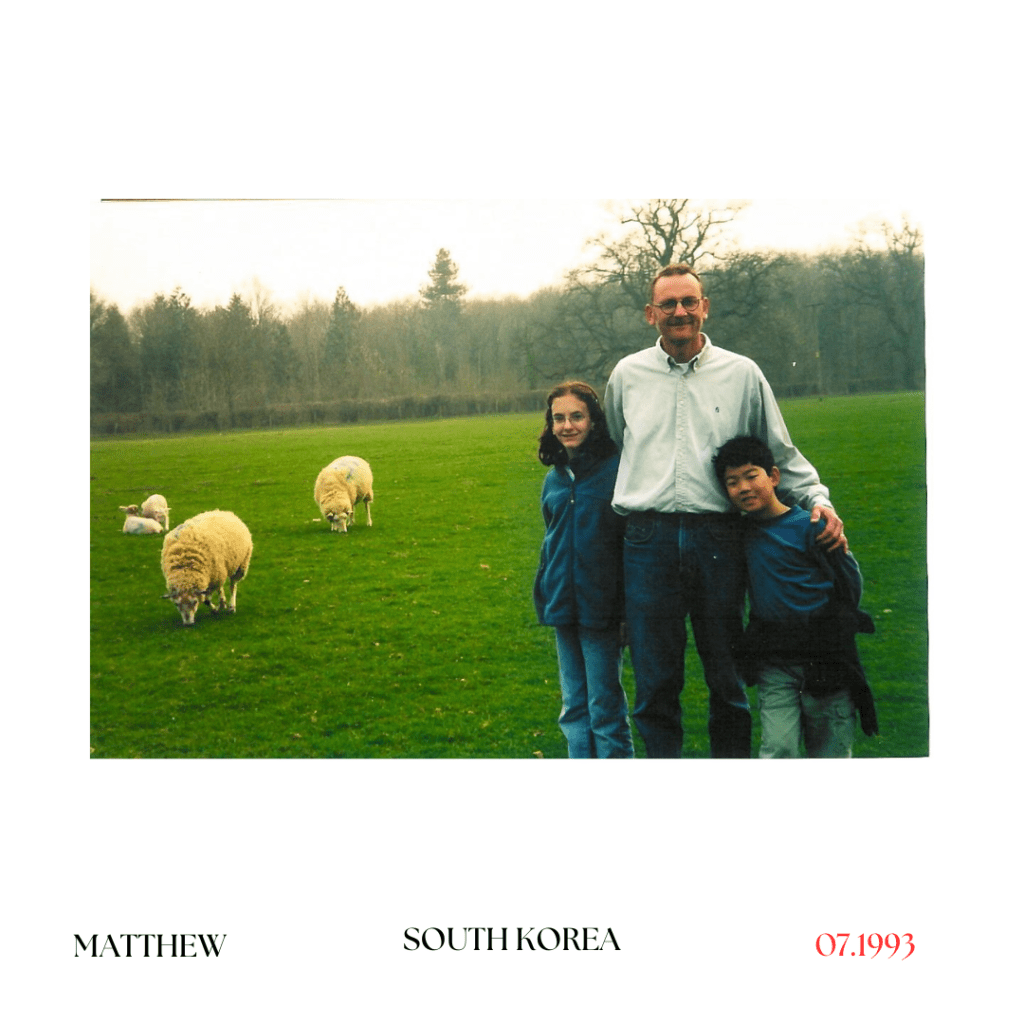

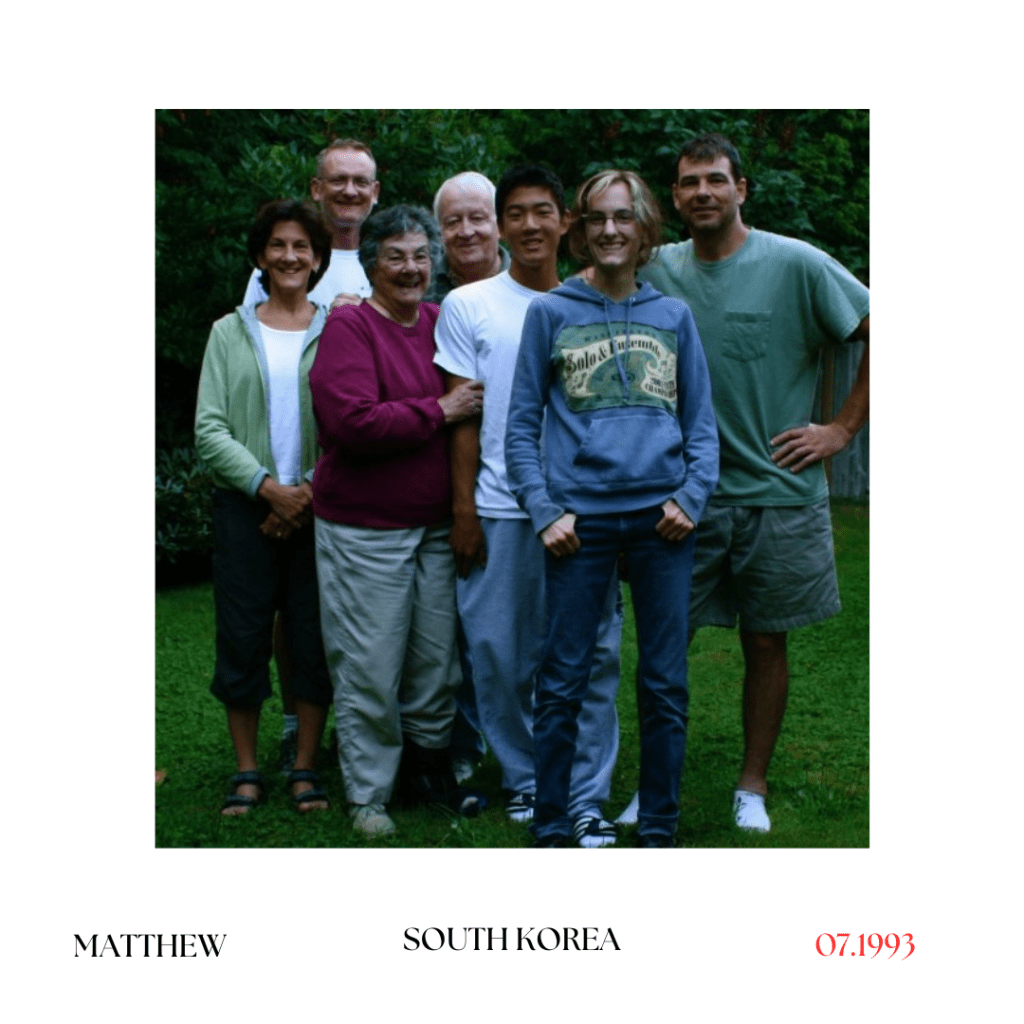

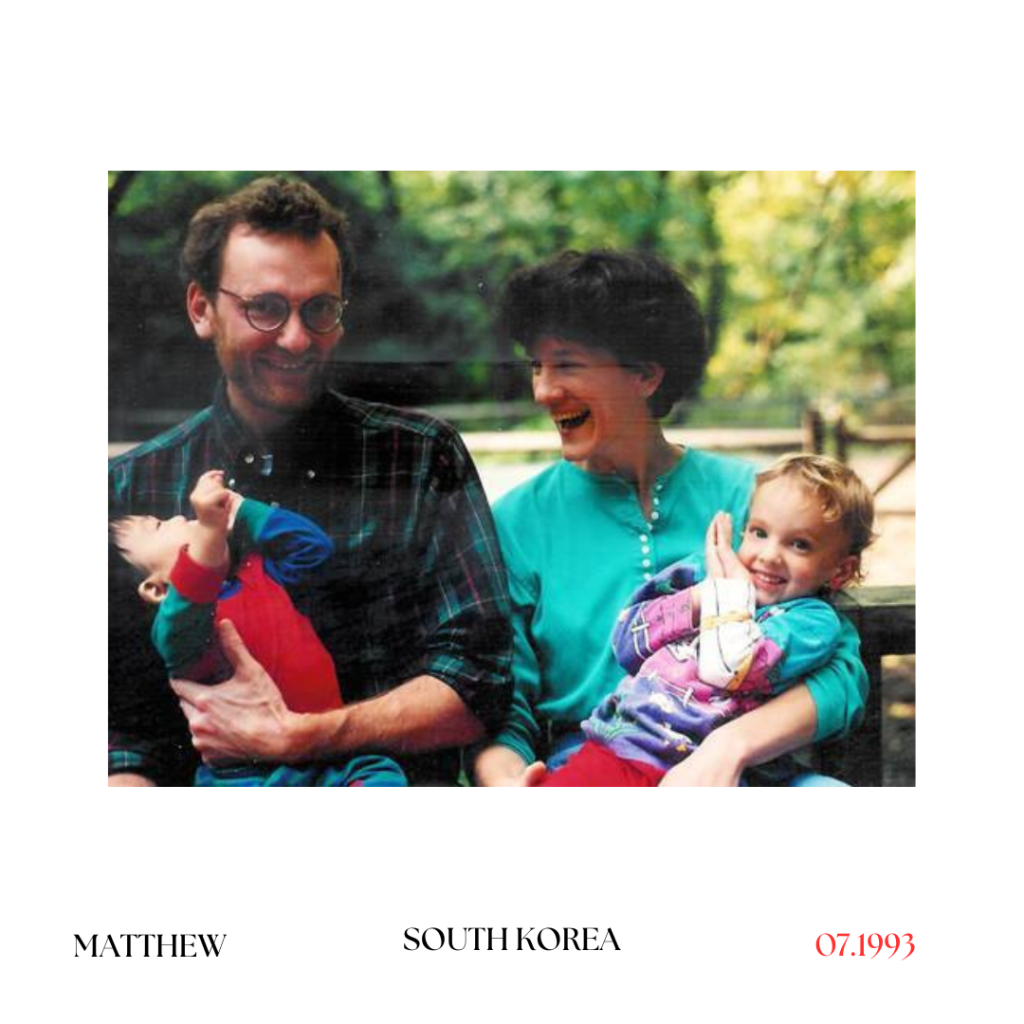

I grew up in a white family, and my sister is biologically related to my parents and is 3 1/2 years older than me. I was raised in Bellingham which is like a fairly homogeneous white town. But as such, I never really thought too much about my identity or who I was. I’m sure you hear about this from other adoptees, but it’s kind of like, you look at yourself in the mirror and you don’t really recognize that you’re Asian or Korean, that you look differently than other people.

It was like that through most of my childhood. I had a really good upbringing, I felt very loved, and I had a core group of friends. But most everybody I knew was white through high school and there were maybe a couple of non-white kids in my class, but I did not feel like I connected with them and didn’t gravitate towards them at all.

It wasn’t until around high school that I even noticed the occasional offhand comment or things that would make me realize that other people in society saw me differently than just being one of the other kids at my high school. And I remember when I was maybe 16 years old was the first time that I asked my parents ‘do you have any sort of information about my adoption or about my biological parents?’

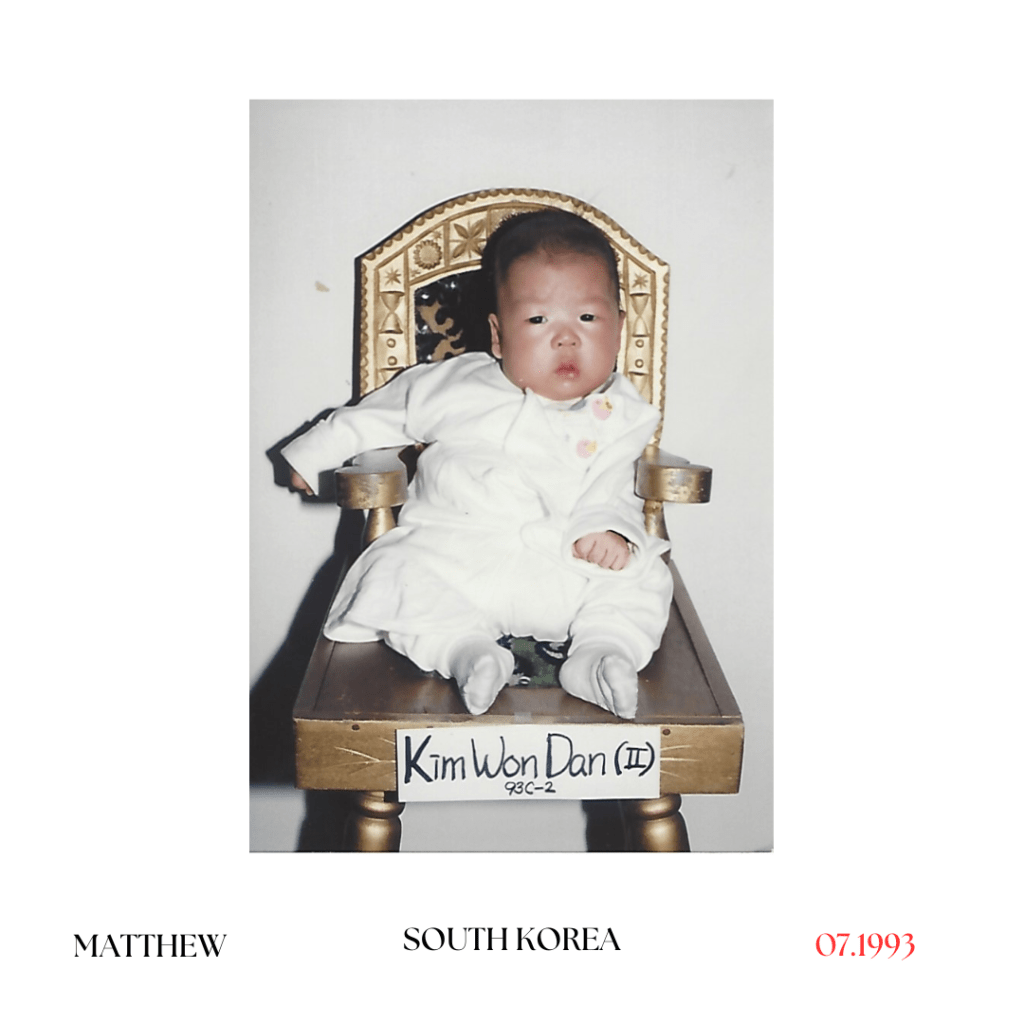

I didn’t really expect them to have anything, but they said, ‘oh yeah we have paperwork, we’ve just been waiting for you to ask about it’. And they gave me a bunch of documents, for the most part info about how I behaved on the flight and my intake forms and all the stuff that parents had to do to adopt me. But hidden amongst all of that was this one-page single sided sheet of paper that had a little bit of information about my biological parents.

And I think it had been pieced together by a social worker and if I remember correctly, it didn’t even have my biological father’s whole name, just Mr. and then his last name. It had three adjectives about each of them and it’s like, okay, did they really know or are they just making stuff up? Like they’re not going to pick anything that sounds bad, right?

It’s like when I adopted some cats and this is a bad analogy, but whenever you see a little write ups on cats at the shelter it will say social, loves hanging out with people, etc—because no one’s going to adopt a cat where the description says it’s poorly behaved and maladjusted.

But anyway, seeing the papers, it struck a chord with me and made me then become really interested in knowing more about my past and it’s something that I didn’t really pursue in high school because I just didn’t know where to begin. I went to a liberal arts school in Southern California and day one, someone knocked on my door and said ‘we’re with the Asian American Mentor Program, you’re in by default because you checked some box when you applied, do you want to join? And I decided to, so I think that was a somewhat formative experience for me because it taught me a lot about the ways I was both similar and different from the rest of the Asian American community. You know similar in some ways about, like social perception and stereotypes and discrimination, but different in just hearing, more about second or first generation Asian Americans and cultural norms and family life.

And just all of these things that go on beneath the surface and spoken languages at home.

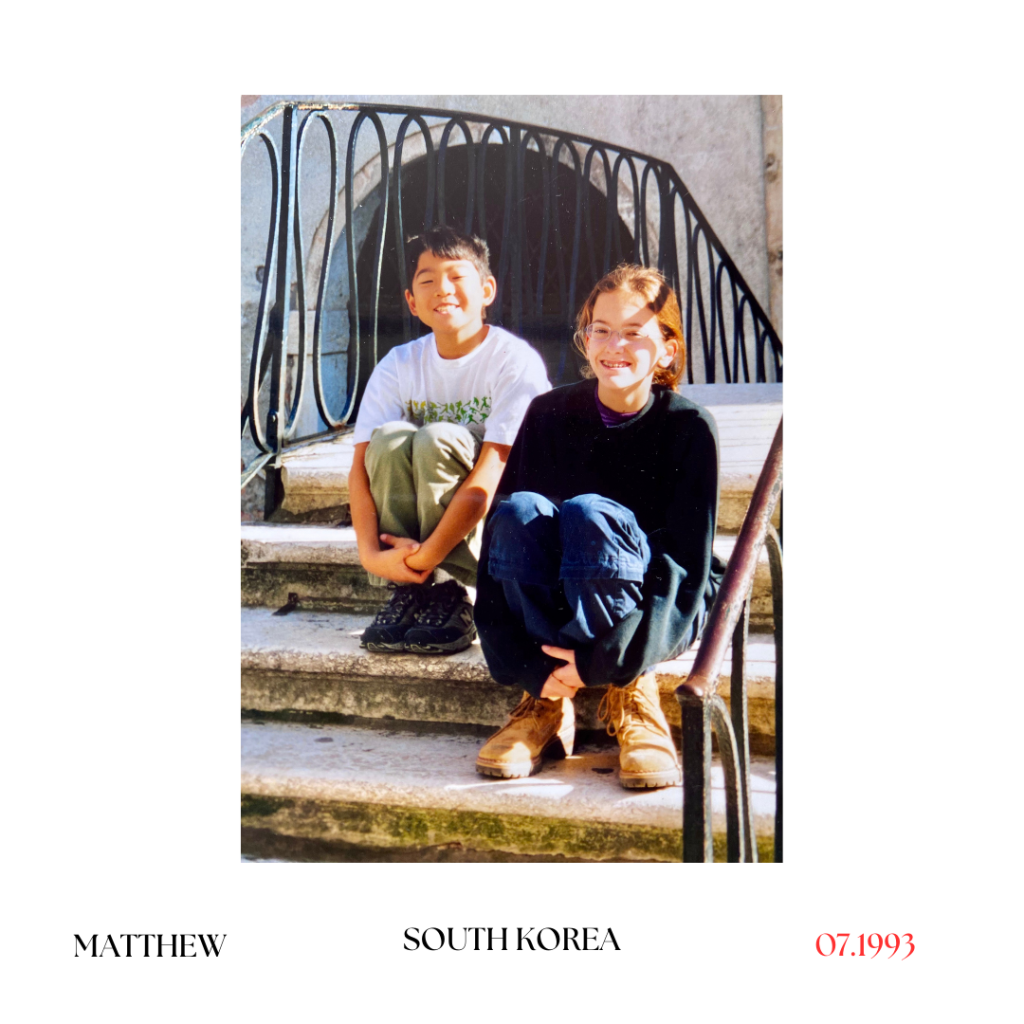

I had none of that growing up, my parents didn’t take me to Korean Camp or Korean school; I had no cultural affiliation to Korea whatsoever. But I ended up finally starting to, like, make some connections with other Asian people. I met someone in my Korean class who was also adopted, and it was my first time meeting another adoptee and that was really cool. I think it made me really want to try and get some answers.

I think I’d come in as an intended philosophy major, although I didn’t end up majoring in philosophy. And so, they assigned me to this English and Gender Studies advisor and she was great but we didn’t meet too frequently because at that point, my academic interests were sort of starting to diverge. But she knew that I was adopted and knew I was taking Korean. She happened to know another professor in the department, an English professor, who was writing a book about Korea and at the time she insinuated that he needed help writing the book and I could go do this summer research project for him and could apply and it would be paid for by the school.

In retrospect, I think they probably just made the whole thing up because, bless their hearts, I think both of them were invested in my situation and wanted to try and help and so, did he really need help? Probably not. Did I actually help? Minimally maybe. I ended up sort of meeting with this professor and he got me on board and took me under his wing. He was Korean American himself and had been to Seoul many times. But basically, I applied for and got the position and officially my role was to investigate the impact of globalization on the counterculture movement in Korea. This was during the peak of the Hallyu Wave and so K-Pop was really big maybe around 2012. But he was doing research on the underground counterculture movement, and punk rock was really popular in Korea as a sort of counter influence to K-Pop. There was this whole scene in Hongdae, and he wanted me to investigate the impact of globalization on that counterculture movement.

In theory, my role was to go to these underground bars and listen to music and investigate, kind of like a journalist. Now I had taken one year of Korean at this point, so I could barely do anything except for ordering at the restaurant and asking where the nearest bathroom was. I was totally unqualified. But anyway, it seemed really cool.

So, it got granted, so I flew off to Korea and I was there for like 2.5 months and I stayed at Ko-Root the entire time. It was a long time to be at a hostel for adoptees having only met like 1 adopted person before in my entire life.

And thinking back it totally changed my life trajectory. In a nutshell I would say it expedited certain feelings inside of me and certain explorations that I probably would have had to do at some point in my life but ended up doing it at a time when I was probably not emotionally prepared. I was 19 years old and had just finished my first year of college and ended up going through some really challenging things. I think it was really hard at the time and hard to process in the years following, but it made me feel much more centered in the long run.

So going in I knew that this was going to be a really challenging time of my life and I didn’t want it to just be this blur and not remember it so I decided to keep a journal while I was over there. I like to write, but I’m not a writer and I’d never kept a diary or journal before.

And I ended up writing the entire time. I was writing like pretty much every single day and wrote like hundreds of pages way more and then I thought I ever would. In preparation for this interview, I wanted to make sure that I’m not talking about this as someone who went through all this and completely forgot everything but the highlights. So, I read it again for the first time in years last night and this morning and it’s very fresh in my head again. It’s just funny how it becomes so much easier for me to talk about this over the years, but it gets consolidated down to just the parts that are easier to talk about while there are parts that I had completely forgotten about.

It’s just so interesting to me because if I hadn’t written it down, I probably would never remember it. And it’s important to me that these memories are preserved as objectively as possible from my very subjective narrations.

Nicole: Did you make friends with the other adoptees staying at Ko-Root?

Matthew: I think everyone that I met is chronicled in the journal. I met people from all over the world: from France, Australia and Germany and South America. It didn’t even cross my mind that people had been adopted all around the world (outside of America) to my naive 19-year-old self.

The biggest thing that I learned and that stuck out to me from the get-go was that a lot of the adoptees I met had serious life events that caused them to be in Korea, driving forces behind being Korea, that were not positive. Either their adoptive family had kicked them out when they turned 18, or they had rifts with their parents, or they felt like they were to go, or they were searching for a sense of belonging somewhere and thought they might get it in Korea. That was the first thing that shattered my very sheltered perspective. I grew up totally fine and I had never even thought about this stuff and then here are all these other people who were struggling and looking for something.

It hits home because if you flip the coin, then it landed differently, and at random I could have been adopted into another family. That was the first big thing that I had to struggle with was, why did I deserve to have this happy childhood when some of the stories I heard were not just unhappy upbringings, but abuse and legitimate trauma. And adoptees are pretty open, right and everyone’s got this shared struggle, everyone’s very comfortable with each other and so you get to hear a lot very quickly.

Of all the people that I met, very few were like me in positions where they were just going just for the excitement or the adventure versus the not-so-great reasons or not having a place to call home.

So the professor was writing a part of his book on unconscious trauma and who’s a better poster child for unconscious trauma than an adopted person. And at the time, sheltered me, I thought this was ridiculous. All of these people are keeping themselves down by blaming all of their problems on something that happened before at the time they were born. Now if you ask me about this now, years later, I would for sure say that there is some truth to it now.

But at the time when I was reading all these Facebook posts and stuff, I was just like, why is no one taking accountability? Why is no one willing to try and raise themselves up? But ultimately, it’s so hard and especially hard when I did have a happy childhood and loving parents, and I had such a strong foundation growing up. It’s an immensely privileged place to come from and to be thinking from.

And all of the adopted people that I’ve met in Korea, like 90% of them, had either first- or second-hand traumatic experiences. There’s a guy who had been adopted by a family that hated Korean people or something like that and so they basically just abused him his entire life because they wanted to exterminate the Korean race or something horrible like that. And another woman who had severe mental disorders because she had been abused by her parents sexually. And one that got kicked out when they literally turned 18, their parents had their bags packed. And the one guy in the news from Oregon who got deported because his parents didn’t complete the naturalization paperwork properly or something like that.

It was so hard for me to comprehend how that could happen to these people. And when they would move to Korea, they had no knowledge of the Korean language or anything, they were just totally alone and had been living in Korea ever since.

That was the first big realization that all these people are here because they’re missing something in their life and not just fantasizing about finding their biological family, but, missing a sense of community altogether.

Nicole: I have a bit of a different experience than you because you went, funded by your university. I went with an adoption return trip, which is a whole other discussion. But I would say it takes a bit of privilege to go on those trips because typically they’re done with the family and I went with my family and other adoptees went with their families, meaning they had to get along at least a bit, you know.

And then the places we were taken to the best places to see in Korea, and you’re shaking the hands of these people who own these adoption agencies. And they’re like, you’re so welcome here. It’s so specific and it’s a form of tourism that a lot of people don’t even realize exists.

But I could write a whole thesis on just adoption return trips. But that being said, I met other adoptees on a different trip that had more diverse experiences, like the ones that you were sharing, but it’s a different view of Korea in some ways, because the adoption return trips are very controlled, super specified. It’s almost like they’re holding your head and they’re like, look here, look here, look here and don’t look to the side. I know it’s not that evil or intentional, but it kind of feels like that.

I would say only like 10% of my time was spent on the research, because anything I needed to do, I needed a translator anyway. I had to get a volunteer from Ko-Root or someone who is bilingual to come with me and frankly, the only thing I was really good at was going to the bars and taking pictures and videos. I would just go in and record things on my phone.

When it came to interviewing them, I was totally at the mercy of whatever volunteer I was able to convince to come with me, so that was a lot more rare. I did some research. I went to the Korean Film Archive and a few other libraries and sort of places that had English research materials. But as far as my on-the-ground contributions, I couldn’t really ask probing questions to the bar owner because I just didn’t have the skill. He was so invested in me, just like having space to just do some self-discovery and I’m incredibly grateful for that.

And the only thing that made me feel better about it was that I felt like he was getting something out of being able to accompany me along the journey and sort of check in and hear how things were going. I think he felt like that was meaningful somehow. And so, I didn’t feel like I was just hitching a free trip to Korea and abandoning him.

So the abbreviated timeline would be, I show up and meet all these adoptees from the world, we exchange stories. I hear all of these terrible stories about birth family searches which again I hadn’t even really thought of. The first person who opened up to me explained that they tracked down their biological mother, but she didn’t want to meet with him and so he’s here in Korea just waiting for her to change her mind. And I’m like, okay, that sounds terrible. And that immediately made me think about starting the birth search. There were 2 parts to me. One was that almost every story I’ve heard has ended badly and been devastating for the person. But on the other hand, I didn’t know when I would be back in Korea, this is a once in a lifetime opportunity. I’m in this space with all these people going through similar journeys, hearing all of them, having gone through the journey made me want to start mine.

Going in, if you were to ask me if I would have pursued this, I would have said, maybe not, but as soon as I got there and started connecting with other adoptees, that’s when the urge really struck me. So, two weeks into the trip, I ended up going to Eastern Social Welfare Society, where I was adopted from, with no appointment, I just walked in. I had sent a couple of emails to them before I left for Korea and when I got there, and no one had responded. So, I didn’t even know if it existed anymore at this point. I just went there and walked in.

The reason this is so fresh is because I just reread all of my writing. I walked in and the woman working asked me to write my name down in English and in Korean. And I wrote it down and she said, ‘oh, it’s you, I’ve been meaning to email you back, but we’re just so busy’.

The woman ended up being incredibly kind and took this interest in my case and helped me throughout the rest of the time I was there and even after she kept in touch with me and still wishes me Happy Birthday every year. I’m really grateful to have had her assistance.

But basically, she finds the same file that I did, but it was not translated to English. It was the Korean version, and so it turns out that the file in Korean had much more detail than the English version.

I learned instantly all of these things about my biological family that blew my mind. I’ll give you some examples. I’m left-handed, and my biological mother is also left-handed.

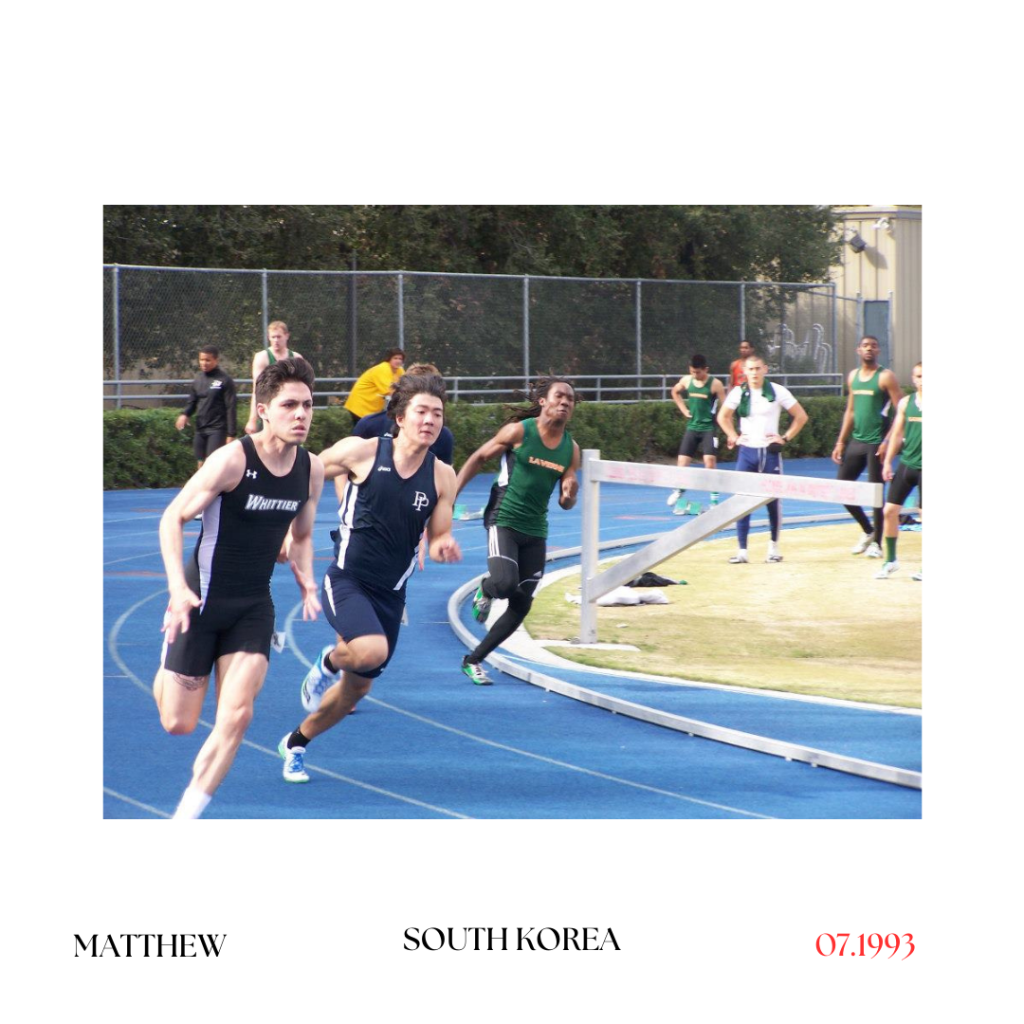

They grew up extremely poor, but both my biological mother and her and my biological grandmother were runners, they were sprinters, and I ran track in college. I was a sprinter. She also studied philosophy and I minored in philosophy. Just tons of crazy coincidences like that just blew my mind how I could be raised on the other side of the world and where everything is totally different, the language and the environment and the resources available to me, and still end up in a somewhat similar place.

I never had any experience remotely similar to that. And so just to see all the genetic similarities was crazy. My biological mother was really young when she had me, maybe 20 or 21 and my father was in his mid-late 20s and he was a construction worker.

When she found that she was pregnant, he left and with all the stigma she decided to give me up. But it wasn’t a family situation, it was more of an out of wedlock, probably unplanned baby situation.

That was a lot to take in. Then she asked me, ‘do you want to start the birth search?

If so, you’ll need to sign your name and the government has this process and we can try’. And I said yes and signed it and left. I didn’t hear anything back from them for weeks. So, in the meantime I met all of these adoptees and there’s like this whole, very interesting, community of adoptees who know each other. And everyone meets up and goes to bars and I was 19 so I couldn’t even legally drink in America, but here I was bar hopping and meeting with up with all these people around the world.

I got a call a month later and they said that the government got back to us and gave us your biological mother’s information. They tried to call her, but the phone was disconnected and so immediately I thought to myself that she’s dead. Like why would the phone not be connected anymore unless like she doesn’t exist. That was just my first reaction. The social worker and the pastor, the guy that ran Ko-Root, very kind and very supportive said she’s probably changed her phone or started a new life or whatever.

Two weeks later, I got another message. So, this was about halfway through my stay and it’s a social worker and she said they had sent a telegram to your mom. And what that means is literally like a postal worker handed a piece of paper to her and confirmed that we found her at a residence, and she received the piece of paper.

I asked what was on the piece of paper and they said it was basically ‘hi I’m a social worker with Eastern’, trying to keep it vague but it should have been very clear to her that it has to do with me. And the paper asked her to contact them.

A few more weeks ago by and nothing and so at that point, I was kind of devastated. I felt like, okay, if she received the telegram in person, why has she not reached out to me. She knows I’m here in Korea or if she wanted to see me, she would have. Pastor Kim and some other people said that maybe she’s scared or maybe she has a new family. And they were all telling me I should be much more assertive in this situation and really try to dig my feet in and make it happen.

Whereas I wasn’t even sure what the right thing to do was, could I be disrupting her life? What if she doesn’t want to see me? What if I end up like the guy who’s just waiting to see if his birth mother changes her mind?

I felt very uncomfortable about the whole thing. Fortunately, I never actually had to do anything because another week later, the woman from Eastern and the social worker reached out again and said that in parallel we had tried to reach out to your biological grandmother because we also got her information from the government, and she wants to meet with you.

And I was like, ‘oh that’s crazy’. And they explained that they didn’t tell me earlier because originally, she refused, saying that she didn’t deserve to meet me and felt guilty. But ended up calling back saying that she had changed her mind. So, they

set up a meeting with me and the social worker who would be the translator and my biological grandmother, and apparently also my biological aunt, my mother’s sister.

So, the story goes, when the social worker called my grandmother, my aunt picked up and didn’t know anything about my existence or the adoption, or the fact that her sister had a kid, but pieced it together from the phone call and then my biological grandmother confessed the whole thing. And then once they both knew, they decided they wanted to meet me.

So, I went down to Eastern and walked in and they’re sitting there. I didn’t know how I was going to feel, but here are two strangers in the room who are unfamiliar to me, who are beside themselves, like sobbing, like throwing themselves at my feet, apologizing over and over with this intense emotion.

And I just remember feeling so numb to all of it and feeling surprised that I didn’t have any emotion really. And I mean, I did, maybe I was in shock, I don’t know. There was clearly something suppressed inside of them for many, many years.

And for me, I didn’t even think about the idea of having a biological grandmother and so I was in shock. We got to talking and I found out that my biological grandmother was the one that convinced my mother to give me up for adoption in the first place. And so, I guess that’s part of why she felt like she carried the extra guilt, because she was the one who forced the decision.

They took me out to eat and they’re both still very poor, and didn’t know any English, but they took me out to one of the nicest Korean BBQ restaurants and fed me until I literally could not eat another bite. I’m sure it was an expression of love or affection. But that whole concept was very foreign to me. I remember being so uncomfortably full and also uncomfortable because they wouldn’t let me pay for it and I knew that it was very hard for them financially.

I was obviously very glad that I got to meet them. They showed me a picture of my biological mother which was the first picture I’ve ever seen which was cool. I still have that photo. And then they also showed me a picture of, I guess I have two half siblings, which I also had never thought about before because they ended up marrying and having kids, two kids. But like she never told the kids about me, obviously. And in fact, they showed me pictures of my half siblings, but asked that I not take any pictures of what they were showing me, and I chose to respect that.

So, I only have one picture of my biological mother. The other thing that asked is that I don’t contact my biological mother. What they told me was that she had recently had back surgery and that it had gone poorly, and she was in the hospital receiving treatment and going through a really rough time in her life.

And they didn’t want to compound the issue. That was really hard for me because I both felt like I should respect their wishes and I’m sure it would have been more stressful.

But here I was actually physically there, able to and eager to try and connect and so I spent a lot of time deliberating over what’s the right thing to do and should I respect their wishes. Should I go against them and try to contact her? Would she want me to contact her? If she had already received the telegram and not reached out, does that mean that she didn’t want to see me or was it not clear from the telegram that she knew I was actually in Korea? I don’t know if that was implied and maybe she would feel differently if she knew that I was essentially at her doorstep.

Ultimately, I decided not to reach out. And I’ve never reached out since, it’s been 12 years.

I ended up meeting my biological grandma and aunt one more time. And it’s kind of an interesting story, so I got really drunk on the last night I was in Korea and overslept and I would have missed my flight home, but someone from Ko-Root came and knocked on my door and woke me up. I was supposed to be out the door already. And she said your biological aunt and grandma want to see you one more time.

She said, they really want to see you. What if we just take the subway to the airport and they can meet you halfway to the airport? So, I packed up as quickly as possible and the social worker met me on her day off and with all of my luggage, got off at a random stop in the middle of downtown Seoul. My biological grandma and aunt were there waiting for me, and they brought a gift for me which was kind of funny. They brought me three very basic nike t-shirts, and it was just a nice gesture. I’m sure I could buy them in America. But it ended up working out and we met and got to exchange gifts. But I almost certainly would have missed my flight if they hadn’t called to spontaneously arrange one last meeting.

I’m super grateful for the social worker that did so much to make all of it happen. And I know that if I hadn’t started the search, I would have eventually felt the need and it might have been a lot harder later in life. Anyway, so I leave Korea and I’m certain that my life has forever been changed and I’m going to start this relationship with my biological aunt and grandmother and eventually convince them to reach out to my biological mother. And then I never did. I never contacted them ever again.

So that’s kind of where it all ended. I went back to Korea with my girlfriend last year just as a tourist visit, that’s it. But that’s the only time I have gone back since. And if you would have asked me, I would say I’m going back every year for the rest of my life, this is life changing, and it just didn’t work out that way. And there are a lot of contributing factors. If it did one thing, it definitely got me more involved with my identity as an Asian American and adoptee and all these other interesting factors. For example, I had really never seen Asian people as attractive in my life. Either western beauty standards but also, I just never felt I had that strong of a connection to other Asian people. And I think that has changed very much as I made other friends in college and met more people.

From an empowerment perspective, going as a young Asian male in college and Korea is very vain society. And I had random people complimenting me and saying nice things. And it felt very validating, and it felt good to “fit in” that definitely changed my perspective for sure.

The other thing I wanted to touch on is my relationship with my adoptive parents, which has always been really special. When I was in Korea I sort of pulled away a little bit from them and I don’t know if they noticed that, but in what was probably one of the hardest times in their life, I don’t even know if I talked to them, I’ve barely, I probably sent them some emails. But like, we barely talked for like 3 months and I’m sure that was incredibly hard for them.

I think they thought that they might push me away if they tried too hard to stay in touch, and they gave me that space which I really appreciated. I remember when I came back, we sat in the front room and talked about everything that happened and ultimately, I think it brought us closer together. From then on out I really felt a change in my relationship with my parents. I think it provided some closure and some understanding of what family means, and it was something that I would say was hard for both of us, but necessary to help us get to a new level of our relationship.

Ever since then, I’ve just felt so close to them. Even people like me who were raised in very loving families and all of that, they’re adoptive parents, have had some sort of issues with getting defensive if they try to look at their files or contact their families. And it comes from a place of love, you don’t want to lose the person that you care about.

I just feel like my parents did a lot without putting any of it on me. That sort of mutual understanding of how hard it was for them, but that they wanted me to do that sort of exploration is what brought us closer together.

Nicole: How did you emotionally recover from that trip?

Matthew: It definitely took a while. For a while it was hard to talk about with people and I couldn’t even begin to talk about it without, even to the people I was willing to share without going way overboard on the details.

Because I felt like I couldn’t just consolidate it down into something without taking away from what it meant to me. So, I would say maybe through collegeish to early mid 20s. I continued taking Korean throughout college. I think in terms of me feeling like I’d be in touch with my Korean side I felt like that would be a constant throughout my life and that’s definitely not how things played out.

And so, for a while I dove deeper into adoptee issues, and the things I’d see on Facebook groups, and the mental health of adoptees, really trying to educate myself on the people I had met and other people that had other experiences. And I wanted to do something to help.

So, I moved to San Francisco after college and there was this guy who was on the board of AKASF (Association of Korean Adoptees in San Francisco) and he reached out to me randomly on LinkedIn-I have no idea how he found me. But I had just moved to the city, and he messaged me and said, ‘you’re adopted, let’s meet up’, but he seemed like a nice guy, so we got food together and he set me up with a few other adoptees who were my age in the Bay area and we instantly clicked.

We were all from upper-middle class backgrounds, went to good colleges, and now had well-paying jobs. And we connected because of our adoptee background, but also a shared social upbringing. One of them moved, but the other became one of my closest friends. But in terms of the adoptee community, that’s pretty much where it all ended. Like here I went through this big thing, where I feel like I really empathized with the plight of all of these people and then I ended up just connecting with people who were like me and didn’t have to struggle as much and then I stopped thinking about it. So, it doesn’t feel great, but I think it’s human nature to connect with the people that you relate to. And some of those people that I met; we have an instant connection because we have so many shared experiences.

But since then, for the rest of my adult life, it’s been around 8 years or so, either I’m not thinking about my adoption side at all or I’m wishing I could be involved, but never actually stepping up.

Nicole: What are some ways now that you feel connected to your Korean self?

Matthew: I think with some of the friendships I have with other adopted people, that’s definitely part of it. My relationship with Korean food and culture and cinema and having been back more recently. Just things here and there.

Another example is with my best friend in college during my senior year, and we would go out to dive bars in a heavily Korean community near my school. We got KBBQ and we were eating, and he made some comment about how I was good at chopsticks, and I looked at him and it was like my fifth time using chopsticks ever. And it sticks with me because of all people he should know that I would not know how to use them. It might have been a subconscious slip up, just with societal perception.

Nicole: I understand what you’re saying because the minute you leave your familial structure, the people that know you best, everyone else sees you first as Asian. Whether they mean to or not, so then the cultural expectations that come with being Asian and of us knowing everything about Korea or having the same cultural upbringing, there’s a huge disconnect. Even within the family structure, I feel like I’ve experienced times where even the closest people in my life expect me to know something about Korea when all that I have learned is external to my family and is 100% intentional.

Matthew: Yeah, that’s one way that I’m reminded whether I like it and not that I am adopted. And there are those times I think all adoptees share, when I’m out with my sister and they just assume we are dating or married or whatever. Or if I’m at a restaurant and I’m not talking to my family, they’ll assume I’m not affiliated. Little things like that.

My desire to be involved in the community has waxed and waned over the years, for example, when INKAS (International Korean Adoption Services) held their event, I was very close to going, but then I ended up not doing anything.

••How do you feel about adoption as an adult? Do you think that your perspective about adoption has changed over the years?••

It’s definitely changed. Naive me, as a kid was like ‘ohh adoption is great. Look at this life that I’ve got here in America. I was probably destined for lower class, and I’ve had objectively a much better life in the US, than I would have had’.

After really meeting other adoptees, I stayed in many cycles of other people coming and going and from all over the world, really the only other archetypes of people that were coming were usually like, young expecting mothers. I think there is something about having a kid that makes people want to come back and resolve their own story before starting their own families.

But most everyone else I met was there because they were struggling or didn’t have a sense of belonging. And I think that immediately made me think that transnational international adoption was unhealthy because of such the disproportionate incidence of mental health issues and abuse and not adjusting well or not feeling loved and all of that that like I think in part is because of the inevitable cultural gap and a system issue of not doing a good enough job of ensuring that these children are going to have good homes. But at the same time, anyone can be a parent, right? There are no qualifications and people are raised in bad environments all the time. So what makes adopted people special?

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking and wishing that domestic adoption was the preferred method, but then digging into how the Korean Government like commoditized adoption after the Korean War and from an industry perspective thinking about how fucked up it is and how they’re basically subsidizing shipping off these kids to different countries, hundreds of thousands of kids and when you incentivize it and you continue the stigma and you’re perpetuating the system where orphans in Korea are going to go through the system because it’s been set up to exist and it’s profitable for the country.

So, I think all of that rubbed me the wrong way and made me really think that international adoption is not a good thing. Since then my position has softened a little bit, but probably more to the fact that I just haven’t been as connected. I don’t doom scroll on Facebook and listen to all of the horrible stories so right now I don’t have as much of an opinion. I think that international adoption should be a last resort, not a primary plan for what to do with an extra kid lying around.

Nicole: The meeting of different people and listening to people’s stories when they experience horrible things in their families that adopted them, that changes things so fast, and a lot of the times, if not all the time, international adoption is marketed by, marketed as kind of a disgusting word to use, but it’s not not true. It’s marketed by churches because all of these adoption agencies are usually religiously affiliated and it’s perpetuated.

••Do you have any advice for other adoptees who have gone through similar experiences?••

I think the single biggest one is just connecting with all of these people from different walks of life who are adopted and hearing their stories. That is the biggest thing that expedited my story and made me feel like I really had a genuine understanding of the situation that wasn’t colored by my own upbringing or sheltered life.

I guess what I’m saying is advocating for is connecting with other adoptees. But having also tried to do that virtually in the past it can be challenging and it’s not easy to do in a healthy way. And maybe doing it through a sanctioned organization will help your safety.

I definitely think everyone should spend time dwelling on it because I think even though it’s uncomfortable it hopes to further your sense of self, and helps you better understand who you are as a person. I think part of the reason that I don’t actively dive into identity now is because things are a little more settled and if I were to stir the pot and think about tracking down my biological mother again and just open up this whole can of worms. It’s a lot and so it’s easier just to let it rest.

For me personally it would be a lot harder to let it rest if I hadn’t done sort of not feeling that burning desire to go. I also think that this is for adoptees, but also parents. I don’t wish I had gone to culture camp or whatever, but I do wish I had learned Korean at a younger age.

Because it unlocks so many doors, if you do decide that you want to do something with it later in life, it’s sort of too late at that point. My Korean is not good, and it will never be great. And I’m also saying this now, had my parents tried to enroll me in Korean language? So, who knows if it would have worked? But also, I probably wouldn’t have wanted to learn Korean anyway, so they probably couldn’t have forced me to. But I think that if you get them a young age before they can start to put up a fight, it would have been nice.

I don’t wish that I had the exposed culture because I think ultimately wouldn’t have changed too much about it, I still have been raised with the same values and norms that I was. And so, my parents, who adopted me to adopt me, but they don’t have any sort of vested affiliation with Korea, they don’t know, they have never even been to Korea, they don’t know anything about Korea and it’s not a big part of their life.

I prefer that way; I don’t want that. I wouldn’t have wanted them to adopt me because I was Korean because they had some sort of fixation with Korean culture just because that feels unhealthy to me too. And I know people who were adopted into those situations. So, my advice to other adoptees is talk to other adoptees but be careful.