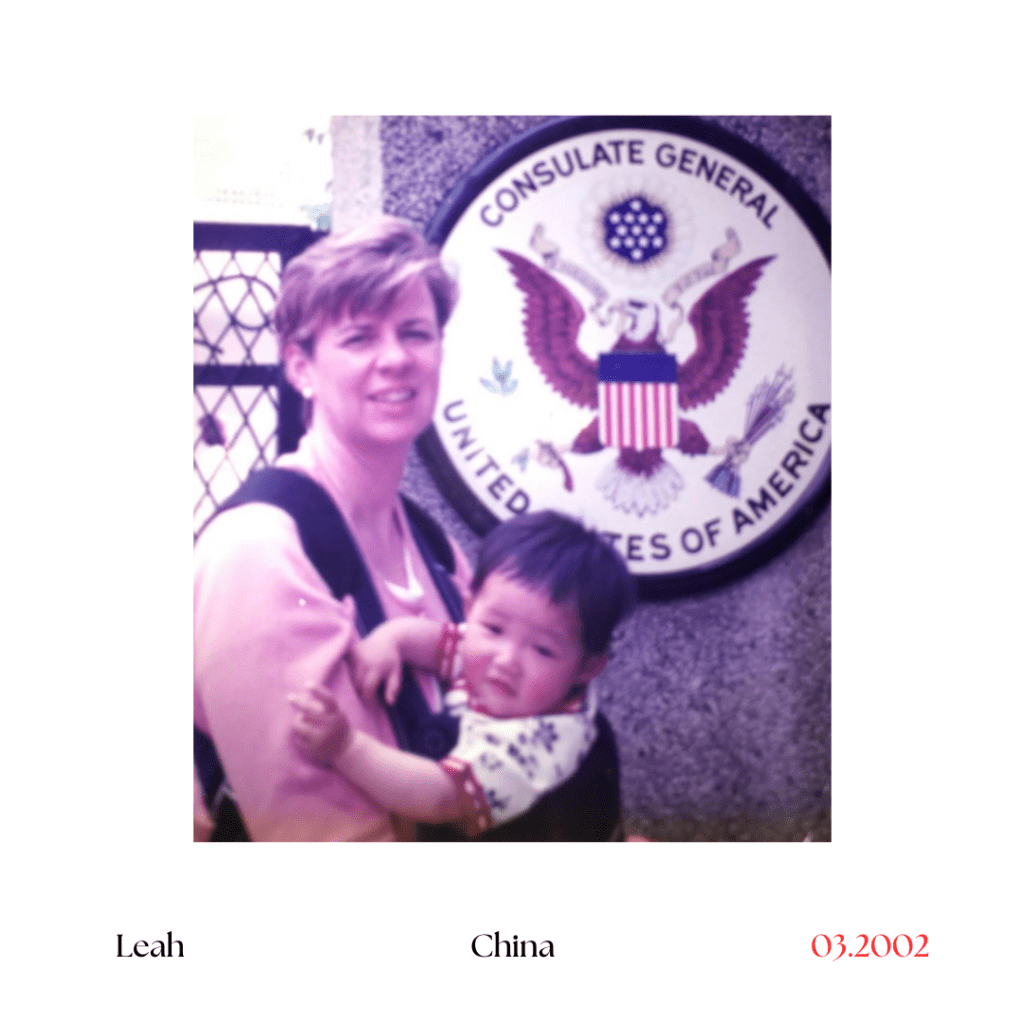

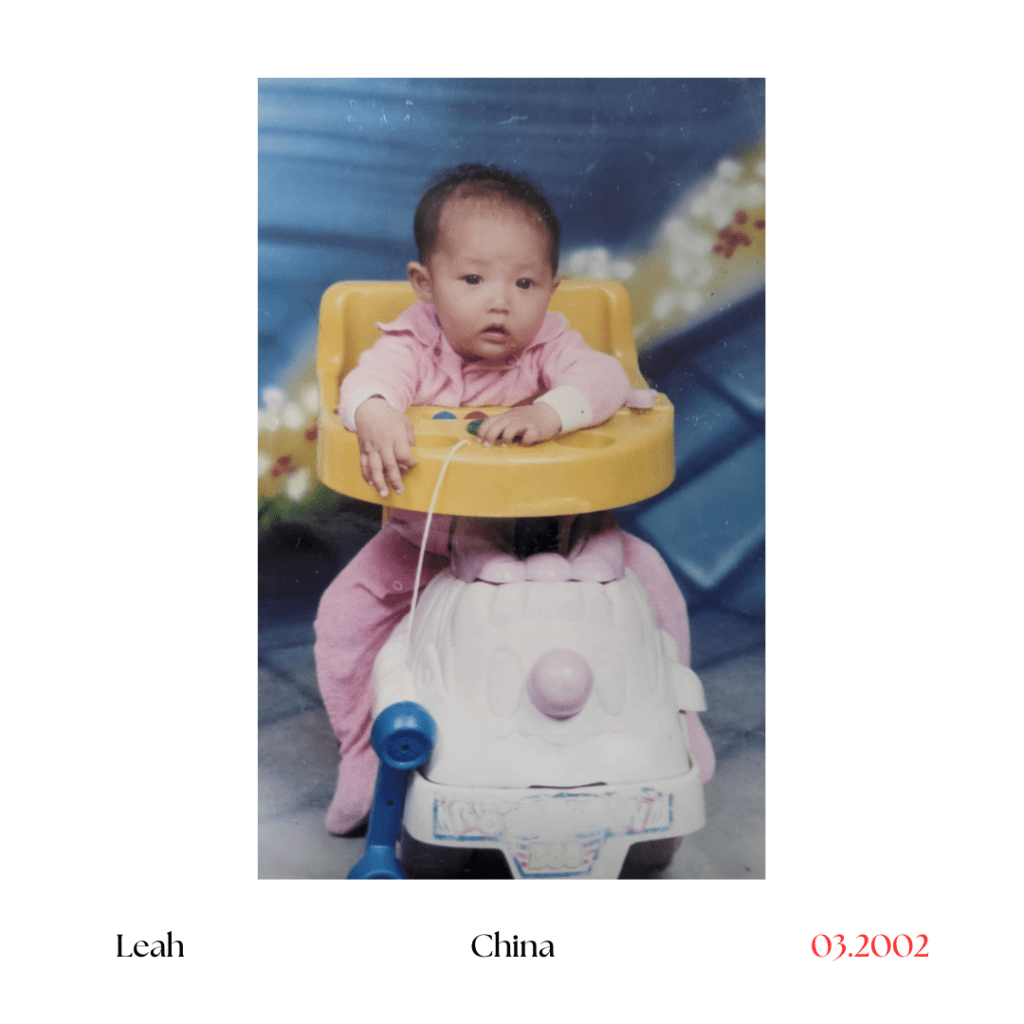

I’m Leah, and I grew up in a small town in Rhode Island. I was 11 months old when I was adopted, and I was born in Guangchang County, a small county in the Southeast part of China

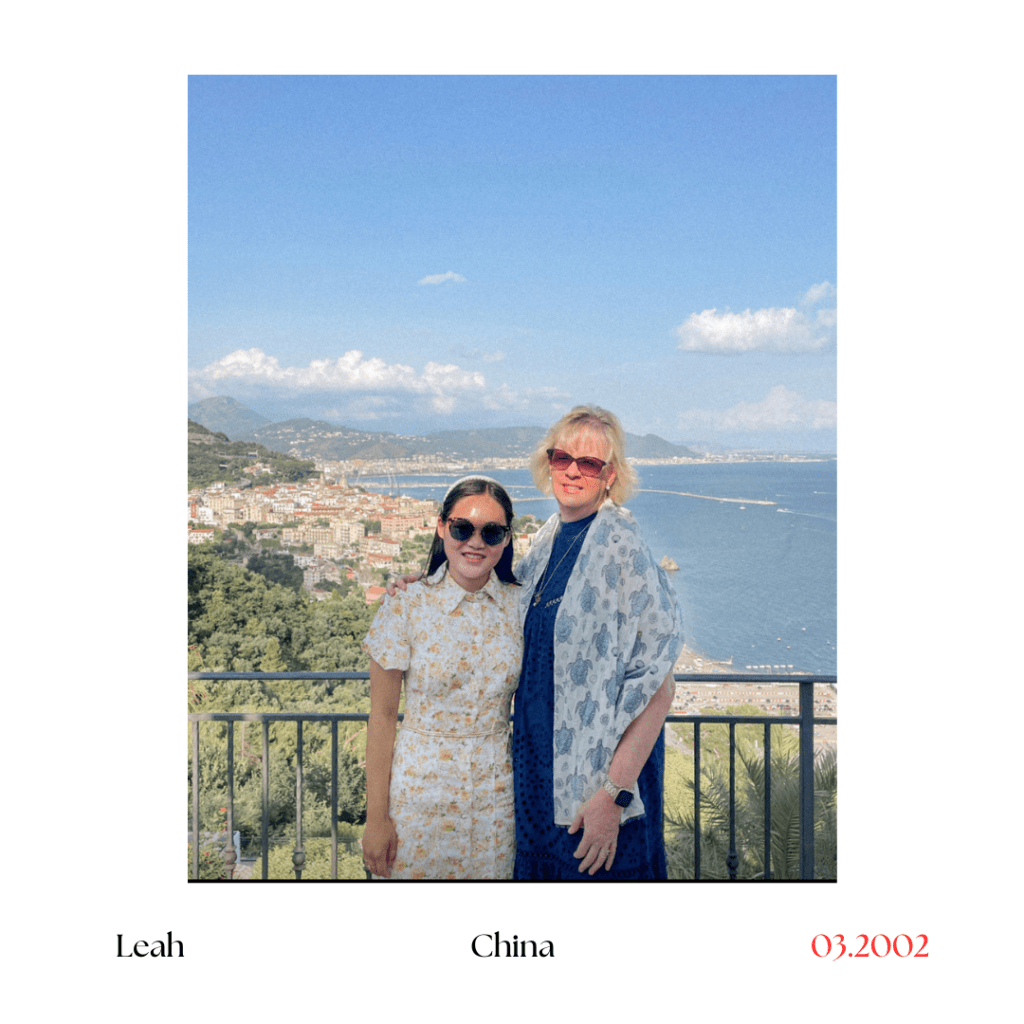

I was adopted by a single mother when I was 11 months old. My family is Caucasian, so being adopted was always very obvious, and I was never under any illusions that I resembled my family. From a young age, my mom read me children’s stories about adoption and Chinese culture. I remember we had a book about adoption at the White Swan Hotel, where many families adopting children from China stayed. My mom never shied away from conversations about my adoption. She worked hard to encourage a positive outlook on my adoption and Chinese culture, so this attitude was always in the background of my childhood.

I was born during China’s one-child policy and adopted during one of the peak years of international adoption from China. Although very small, Rhode Island had a strong community of adoptees from China at this time. Many families from New England used the same adoption agency. When I was younger, the agency would host different events throughout the year for families with adopted children from China or parents waiting to adopt. Adoption seemed very normal to me as a child because I knew so many people who were adopted. Of course, there were these events with all the Chinese adoptees, but I also went to daycare with other children adopted from various countries. About a year after my adoption, my mom went to one of these agency events and met another prospective mother from Rhode Island. It just so happened that her soon-to-be adopted daughter was from the same orphanage as me. The family turned into lifelong friends, and we grew up together. This relationship always felt special; what are the chances that two babies from a rural orphanage in China end up in the same state a year apart?

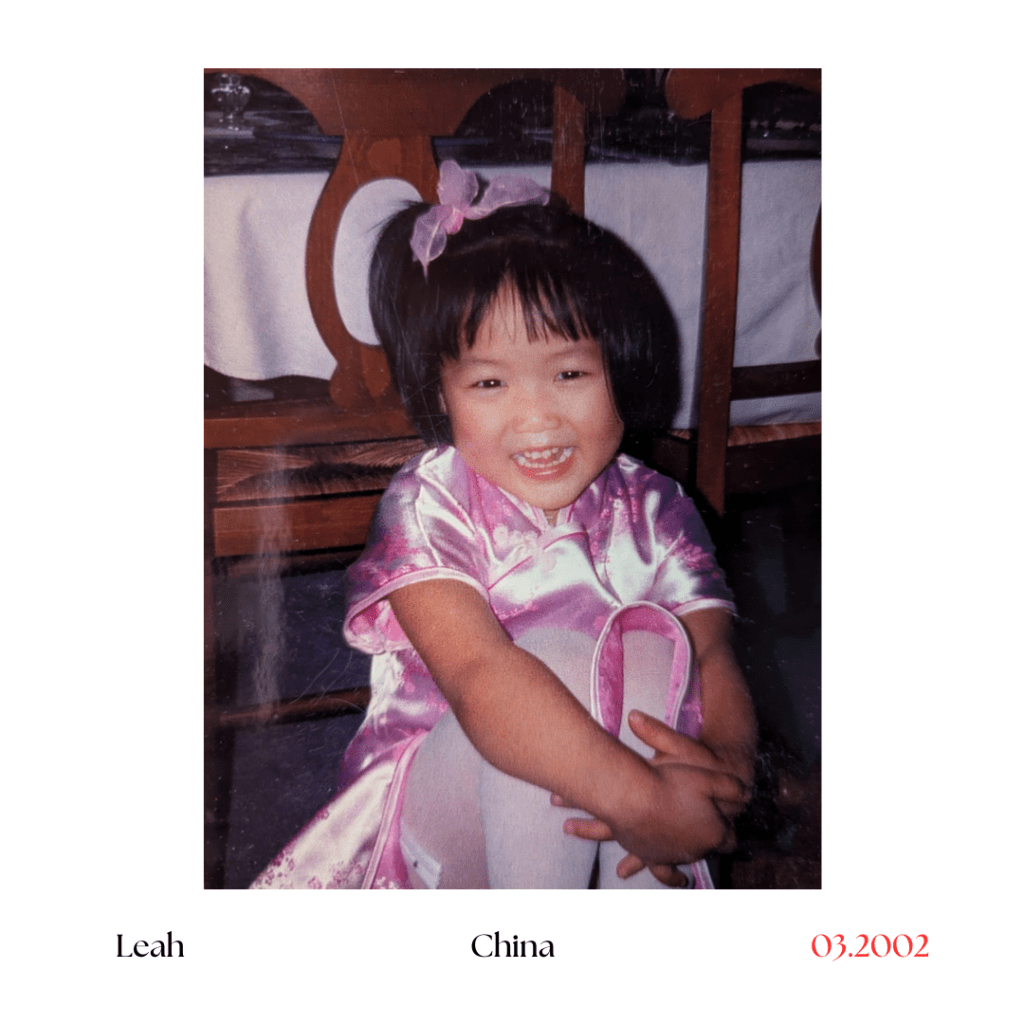

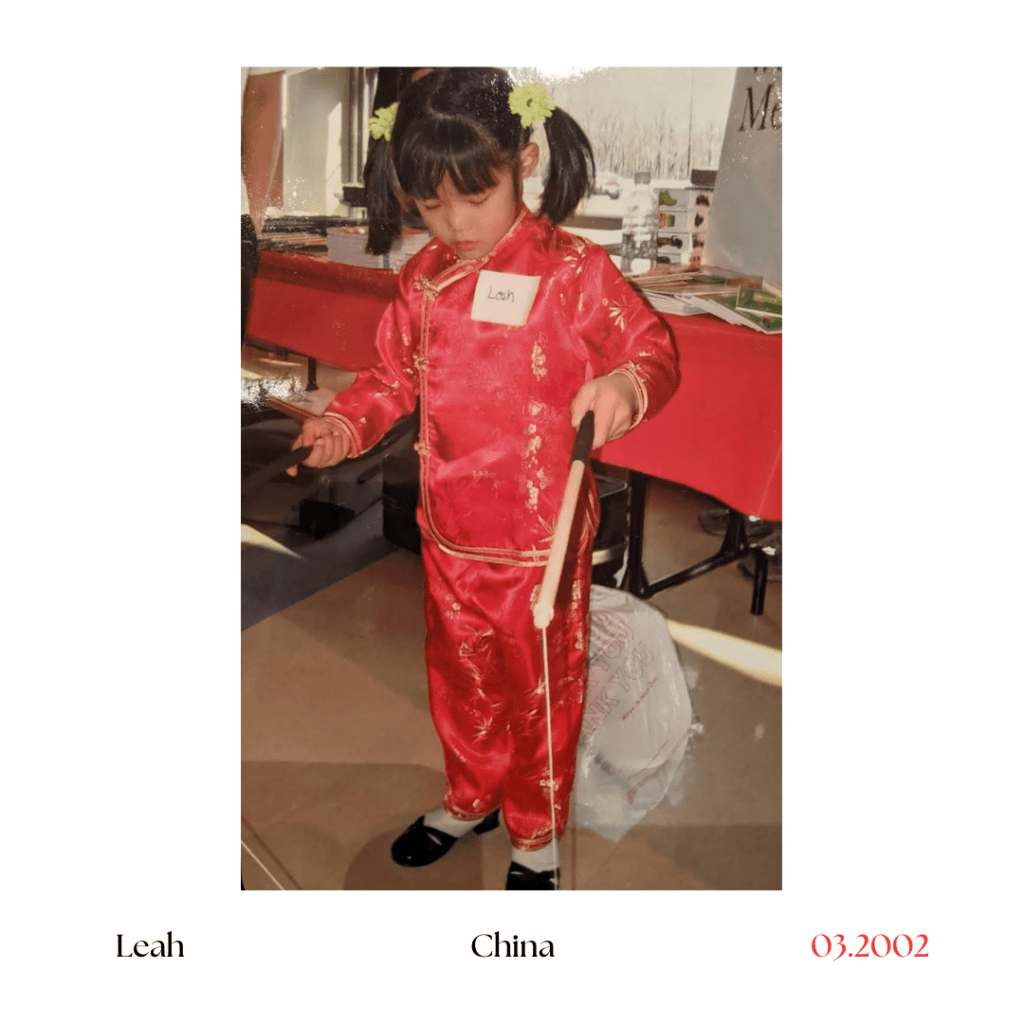

When I was going into kindergarten, my mom decided that she was going to sign me up for Chinese language and culture lessons with a woman, originally from China, who made a business out of teaching the Chinese language to children in Rhode Island. I took these classes about every other week from kindergarten to 7th grade. The class was basically just adopted children from China. As part of this class, every year during Chinese New Year, we would perform at various Chinese New Year events around the state. It was a tiring January and February, but also a lot of fun. I got to wear my Chinese clothes, put on makeup, dance with my friends on stage, and at the end of it, I would receive a red envelope with money. It wasn’t something I consciously thought about at the moment, but looking back, these were the few months in a year when I felt special to be Chinese and not just different.

Once I got to elementary school, my relationship with being Chinese changed. Suddenly, I wasn’t in an environment with other adopted children, and I was one of the few people of color in the school in general. I was often teased, and I struggled with feeling different. So, having this moment every year where I wasn’t teased in any way for being Chinese because I was constantly at events with many other Chinese people, Chinese adoptees, and their families, and people just wanting to celebrate the culture, was such a defining aspect of my growing up. I didn’t know this until recently, but one of the reasons my mom enrolled me in this class, specifically, was because she wanted me to have a Chinese female role model to look up to. She knew she couldn’t fulfill that role herself.

At the time, there weren’t many Asian women in the media either, so she wanted to give me someone I could recognize myself in and who was successful in what they wanted to do. There were many times when I resented having to go to these language classes because it made me different from my classmates at school, and just emphasized the fact that I was Chinese. Now that I’m older, I appreciate what my mom was trying to do. I’m very grateful to have a mom who made it a priority to surround me with people and give me environments where being Chinese was normal and celebrated.

I’ve always had a very positive outlook on adoption. Of course, many aspects are challenging, and there’s always the lingering, often unanswered, question of identity. This opinion of adoption is a product of my upbringing, though. My mom has always said that I’m the best thing that ever happened to her, and she never made it seem like adoption was second-best to the more traditional way of having children. I’m her daughter, and that’s that.

While I didn’t struggle with the concept of adoption internally, I was vulnerable to other people’s perceptions. Kids (and sometimes adults) don’t always understand the adopted family dynamic. When I was younger, kids would say things like, ‘You’re not really a part of your family’, ‘That’s not your real mom’, etc. Perhaps they weren’t meant to be malicious, but they certainly felt that way. Sometimes, the comments weren’t even directed at me, but felt very personal anyway. I often overheard children use adoption as a way to insult one another. There are all these deeply ingrained misconceptions that blood signifies familial strength and love. I’m grateful that I grew up with a mom who was proactive in teaching me otherwise.

Being part of an interracial adoption, I struggled a lot with my racial identity. I was rarely proud to be Chinese; if anything, it made me uncomfortable. Outside of the community of Chinese adoptees, I grew up in an environment that lacked diversity of any kind.

My entire family was white, and I just saw myself as part of that family unit. Even though I knew I was Chinese and that I looked different, I don’t think I saw myself in the same way others perceived me daily. I was just Leah and could have just as easily looked like anyone else in my family.

The moments when I had to confront my race caused a sense of dread. In elementary school, there were always comments about the way I looked and the ‘weirdness’ of my distinctly Chinese features. As I got older, it was less about physical appearance. In the U.S., China is always in the news, and oftentimes, there’s a negative perception of the country and Chinese people. I didn’t feel Chinese, and I didn’t want to be associated with something that was so negatively talked about, because if something was said about China within earshot, I was typically the person people looked at afterward. It truly made me want to crawl out of my skin. Honestly, it wasn’t until the pandemic that I decided it was time for me to reconcile with the very basic fact that I am Chinese and will never not be Chinese or perceived as a Chinese person at any point.

It took a while, nearly two full years, for me to finally be at peace with my race.

Nicole: How did you do that?

Leah: The pandemic was my turning point; it was the first time I really felt in danger. Not that I hadn’t received racist comments before, but the microaggressions were all things I could internalize and pretend didn’t happen. During COVID-19, I was constantly seeing videos of Chinese and East Asians being physically targeted, and it was scary. I remember being terrified to go to the grocery store out of fear that I would cough and just be attacked. I’d always mentally run away from being Chinese, but at this moment, I just wanted to completely hide from the world.

I think the pandemic and the heightened anti-Asian sentiments put everything into perspective. I realized that no matter what I did or where I went, I would always be perceived and treated according to my race. It sounds strange, but accepting that I was Chinese was my first hurdle. Even being able to say ‘I’m Chinese’ and not feel any sort of discomfort is a huge accomplishment for me.

Getting to that point was purely a matter of self-reflection. The world was in quarantine, so I had time. I thought about all the ways being Chinese affected my life. I completely just unearthed every buried memory I had of times when people treated me differently and all the emotions I had internalized. In my day-to-day, I always felt very similar to my family, and close friends would joke that I was basically white. When I looked back at my life, I realized how deeply being Chinese shaped my identity, purely based on how I was treated.

I’ve had other struggles in life. The more I reflected, the more I was able to see that my discomfort with my race was the root of lots of other problems. It was shocking. Simply reflecting and acknowledging the microaggressions for what they were gave me such a different perspective on how my life had gone.

Nicole: For sure. I relate to what you’re saying, and when you’re talking about like, even acknowledging the microaggressions, for me I had some pop into my head that I completely had forgotten about. And then I had to un-gaslight myself and be like no, Nicole. That really happened. That really happened.

Leah: Yeah. It was such an emotional time because I think I built up an identity based on the person I aspired to be. Of course, that person was missing essential elements of my actual DNA, so taking that step back and looking at the reality of the situation was very difficult.

During my self-reflection, I realized I held a lot of anger for the times I felt like my mom wouldn’t take my side when a microaggression occurred or a racially charged comment was made. I realize now that it was because she didn’t understand how offensive the small ‘harmless’ comments were. She’s never experienced racism, and certain rhetoric is so normalized that she couldn’t identify a microaggression. I think it’s hard to teach your child how to deal with the emotions stemming from receiving such comments if you yourself have never felt it.

It was a lot of that sort of healing work, and once I got to a place where I was more honest with myself about the different things that had transpired throughout my life, and why I acted and thought the things that I did, I was more willing to have conversations with my mom.

And those were really healing.

Nicole: It takes a lot of strength though, so props to you. That’s a lot of emotional work that, like a lot of people, won’t have to deal with.

Leah: No, and I’m happy for the people who don’t have to deal with them because it’s really tough. I think being Asian in the U.S. added another layer to it. Asian American history was not part of my education, and racism towards Asians certainly wasn’t covered. In general, I didn’t grow up hearing a lot about racism towards Asians either. I think that is why I gaslighted myself for so long. It seemed like no one else was acknowledging that it existed, so I felt like, ‘Oh, I’m just too sensitive’. Now I look back and can just objectively say that racism was prevalent in my life. My only Asian role model in the media was a fictional character, you know? All these things shape you.

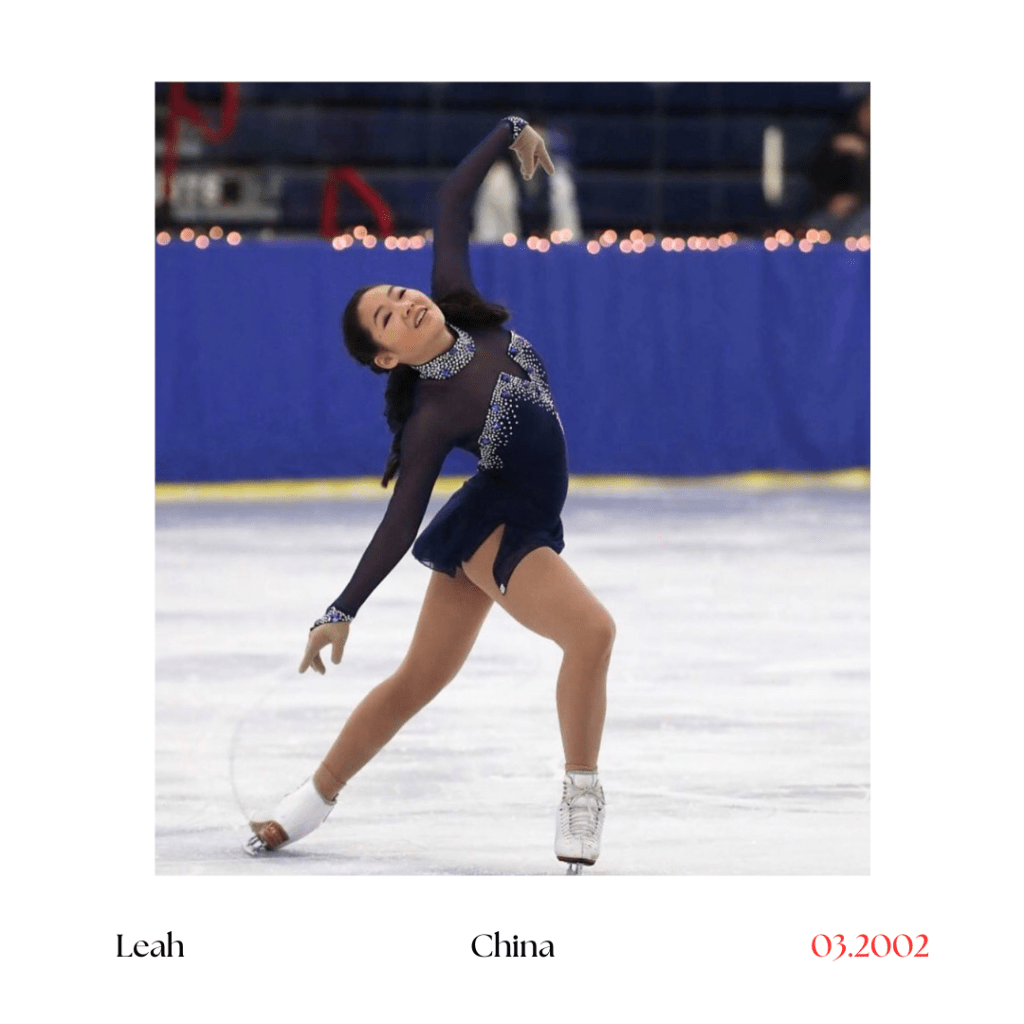

I was reading the posts of someone else you interviewed who talked about how the beauty standard affected them. That was a huge thing for me, especially since I was interested in fashion and all the aesthetic-driven industries. The way it affected me was so subconscious as well. It never occurred to me that adding more Asian representation was the solution. I just thought ‘No one’s ever going to think I’m beautiful’, ‘I can do nothing about this face’, and ‘Everyone who’s telling me I’m beautiful is a liar’. It was completely disheartening.

Nicole: I hear you. I remember middle school putting on mascara needing an eyelash curler so my eyelashes could look longer and having mono-lids and wanting to do 2010s smoky eye or something like that. I couldn’t do that because I didn’t have the same eyes or I didn’t have the same eye shape or brow shape and these things really affected me, so I really relate to that too. I like how you said disheartening. It was completely disheartening.

All of the subtle things hurt the most because when it’s happening, you don’t realize it’s part of a bigger problem. You’re just like, ‘Oh, it’s a me thing. ‘ I really internalized so much of it, and I didn’t even realize how mean I was to myself. I remember a few years ago, I was watching a Vogue Beauty Secrets. In one episode, they featured an Asian woman, Greta Lee. She was one of the first Asian people I’d seen featured on the channel. I remember going through the comments, fully expecting people to be hateful because I simply was not used to seeing Asian women portrayed in Vogue. Instead, all these people were saying how beautiful she was and that she was the most gorgeous woman they’d ever seen. That, for me, was a shock.

That was a very defining moment in my healing process, to be honest, because I was like ‘Oh my gosh, it’s possible’. Being Chinese doesn’t have to be this ugly thing. You can still be beautiful, and maybe you are beautiful already.

Nicole: I hear you. I remember that same idea burst only a couple years ago too, and it’s like, so I’ve really been living like 23 years of my life thinking that I’ve been ugly this whole time. How horrible. What awful messaging I was giving myself. But then that translates to the rest of the media, and how the representation of Asian people is just not there. I mean again, like you’re saying, it’s getting way better. Thank God, but when it mattered for us like middle school era, high school era, that wasn’t there. And typically, if you’re growing up in a Chinese or Korean or Asian household, you could look to your elders to know how to do makeup for an Asian face or to or for Asian eyes. Or how to accentuate our features instead but I felt like I needed to make sure my eyes look big and I was just talking about like the Nix jumbo eye pencil. Do you remember that? Hahaha and like tight lining your bottom lash line with white to make your eyes bigger.

Surely tried it all. That was the hardest part for me growing up, and it affected me in ways I didn’t anticipate. The beauty aspect impacted the way I approached a lot of my first relationships. It’s surface-level, but I genuinely thought very few people in life would find me attractive, and because of that, I didn’t value myself enough in relationships.

When I was doing all this reflecting, everything boiled down to the fact that I felt like being Chinese was a burden. I tried running from it for so many years, and it’s so exhausting because you’re always reminded that you are Chinese. The way I explain it to people is that when I look in a mirror, I see my facial features. I don’t consciously register that I am Chinese. This is how I look. Then, at the most random moment, someone will make a racially-charged comment. Maybe it’s like getting a rude comment when you’re wearing a costume, but you’ve forgotten you’re wearing a costume, so it takes a second to register.

Nicole: I agree. And not having the vocabulary to defend myself, I didn’t know how. I didn’t know how to explain the nuances of being adopted when I was like 8 years old getting harassed? Having little comments from my peers about being Asian. I mean it’s horrible.

A lot of the racist comments I would get, people would always assume and they didn’t know any other Asian country, so they always would just generalize and say Chinese and how they would use it in a really rude way, and not being able to defend ourselves was really hard.

And it’s really difficult when we’re seen externally to the world as Asian and then our family, though, sees us as we are. We just are what we are, but the racist implications start when we leave the comfort and familiarity of our families. And to not have the people who are closest to you understand that we were just children. How are we supposed to articulate these things?

That was a lot of my individual, personal work to get to that point because it was exactly, like, how do I reconcile being mentally 100% something and physically 100% something else? I just didn’t know how to navigate that for so long.

Having conversations with my mom helped. Now, I can be grateful that she gave me the opportunity to connect with the Chinese culture and made sure I always had a Chinese role model and a community of Chinese adoptees. When I was growing up, I didn’t see it like that. For instance, I did not want to take Chinese lessons. I wasn’t someone who longed to go back to China or felt like there was a part of me missing. I felt pretty complete in that regard. If anything, I thought it was unfair that I was being forced to acquire a language or culture I didn’t want to recognize as mine.

Talking about everything years later helped me understand her motivations, but it also gave me the opportunity to be honest with my mom about how everything made me feel. It was uncomfortable at first because I didn’t want her to feel like she had been a bad mother. I felt guilty that I was just telling her years’ worth of repressed emotions on a random day. I didn’t want her to feel bad for her decisions because there were just certain things I don’t think she could have anticipated. Before we had this conversation, I tried to imagine what it would feel like to be in her situation: be a first-time mother with a baby of a different race. I realized that I also didn’t have all the answers or perfect solutions to the questions I grew up wanting answers to. Also, I was the oldest amongst our close adoptee friends, so there weren’t a lot of people she could look to for advice.

Nicole: Yeah, she was paving the way.

Leah: Exactly. And she had a community around her, people who were similar in age in terms of adoption, but it did very much feel like paving the way.

There was a very short period in 2021 when there was a three-day Stop Asian Hate movement. At the time, I had a blog, and I had been doing all of this mental work, so I decided to dedicate a blog post to the movement. I was terrified because most of my followers were people I knew personally, and while they were friends, I knew they wouldn’t be able to relate. Since I also had never spoken about these issues with any of my friends, I wasn’t sure what reaction I would get. Anyway, I shared a draft with my mom, and when she sent it back, all she said was ‘It’s time for you to tell your truth’. I sobbed instantly. It was all the validation I needed at that moment. It meant so much to me knowing that my mom had read everything I had to say, tried to understand all my emotions, and was empathetic. I think this is one of my favorite mom moments.

My mom and some of my friends shared my blog post with people they knew or just more generally on social media. I got some feedback that my post resonated with people and encouraged others to talk to their families about their experiences for the first time. It was heartwarming to know that my moment of vulnerability was worth something and made others feel less alone.

On the other hand, the reactions weren’t all supportive or positive. Unfortunately, there are political associations with topics of race. Some of my friends weren’t able to see past the politics of it. They could separate the Stop Anti-Asian Hate movement from me being Asian. Emotionally, I had to figure out how I felt about the people in my life who had the mentality of wanting to support me as an individual but didn’t want to support the cause or didn’t believe the problem existed in the first place. It was very difficult to have to confront where those lines were drawn for people.

So, it took almost two years of mental work to be completely at peace with being Chinese. It took me some time to figure out what the end goal really was. I was trying different things. I knew someone who wasn’t adopted but was very proud to be Chinese. He was eager to share the culture with me. At some point, I realized that wasn’t really what I wanted. It felt too forced. I couldn’t spend 20 years building one identity, then at 22, submerge myself in a culture and identity I had spent just as long trying to run away from. It got to the point where I realized pride was not my end goal.

Being at peace is enough for me.

It’s such a personal thing, though. I have adopted friends who are fascinated by the Chinese culture and want that connection, and I have others who are even less interested than I am. I think you have to find where you fit in and be okay with whatever place you choose. I don’t think it’s anybody else’s right to tell you that you need to be more or less of something. It’s an emotional journey, regardless, and I think you have to do what’s best for yourself.

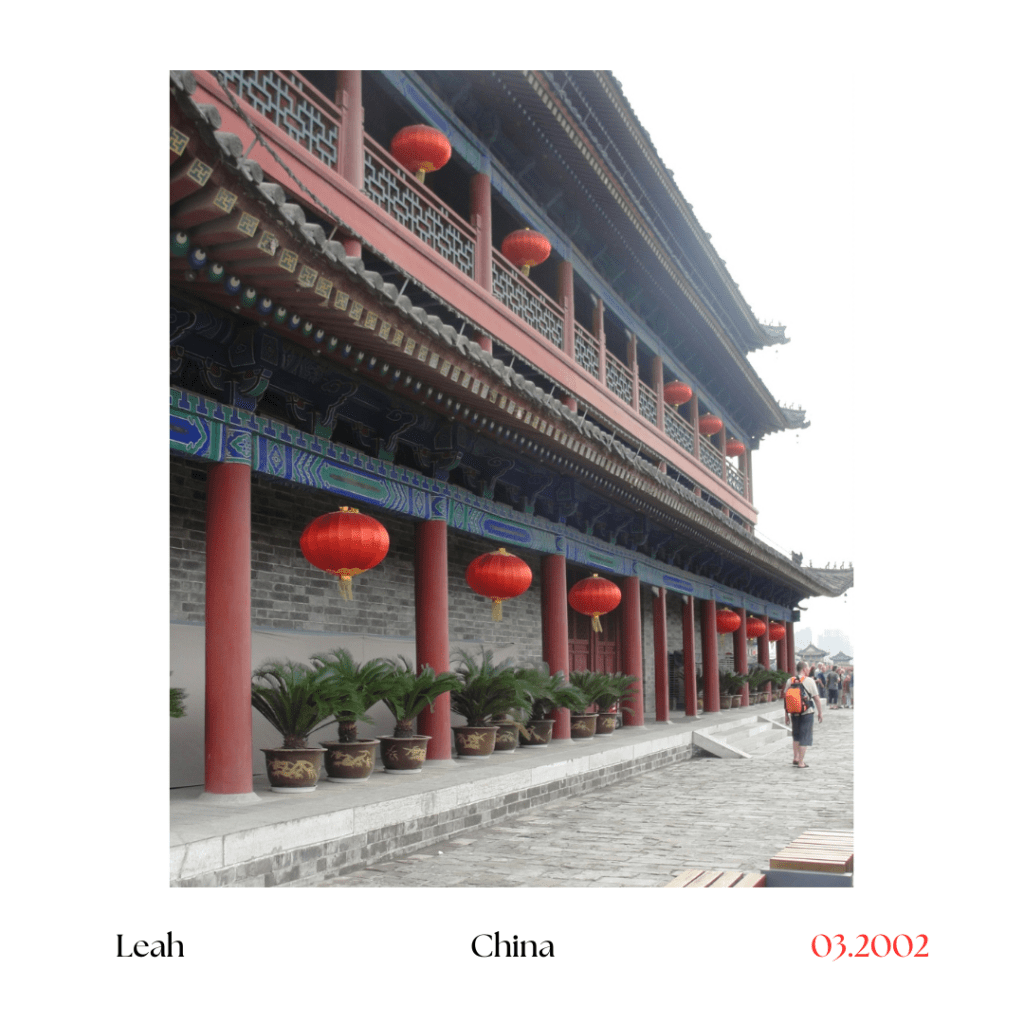

I should also mention that I returned to China with a few other families from the adoption group for a ten-year adoption reunion. It was a two-week trip that took us all over the country, including the city where my mom adopted me. Two of the girls who were traveling with us were from the city, but I was in an orphanage about six hours away. Those girls had the opportunity to visit the orphanage where they were as babies and meet their foster mothers.

I remember when we went to the orphanage, they had made a welcome banner, and their foster mothers shared stories of when they were babies. It was the only time I felt a strong desire to reconnect with my past. Emotionally, I don’t know what that experience was like for the two girls, but it made me feel like I was missing out on something. I was at an age where I had started writing essays in school about being adopted, all centering around the mystery of my birth family and having a part of me that may never be solved. Being in that mindset, it bothered me not being able to have an answer in the same way the other girls could. Even if they weren’t meeting their birth parents, at least they had something.

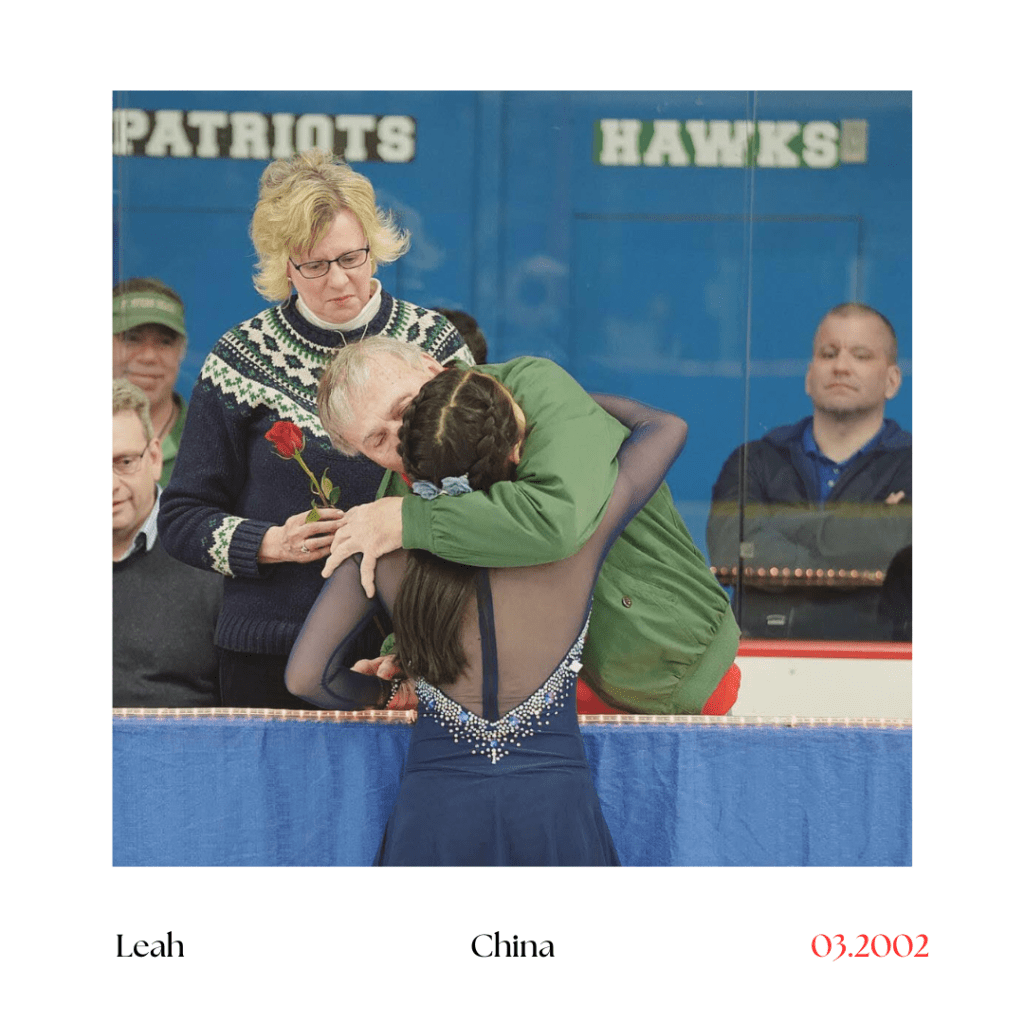

Growing up, and still to this day, my mom has always given a very special place to my foster mother. On my Gotcha Day, I always get three roses to represent the three mothers of my life: my adoptive mom, my foster mom, and my birth mom. My foster mom was always part of the story and someone my mom was thankful to for taking such great care of me before she adopted me. It would have been nice to meet her.

Nicole: It’s really cool. But I understand it’s challenging to see people have emotional experiences with biological parents or foster parents because it is quite a dreamed of scenario for an adopted child.

And especially going back with other adopted kids, I went back with an adoption agency program, and it was challenging to see other people have those experiences, but it was also really beautiful because it was like, Oh my goodness. Again, as such a dreamed of experience, lived out in front of you. But it’s hard not to have that curiosity or that flame ignite inside of you because it’s something I’ve always wondered about.

Leah: Definitely. Seeing the orphanage in China was an experience that really shaped my perspective. In 2012, orphanages were less crowded and perhaps better maintained than they would have been in 2001 when I was born. Again, I’m from a more rural part of China, so I can only imagine what my orphanage looked like.

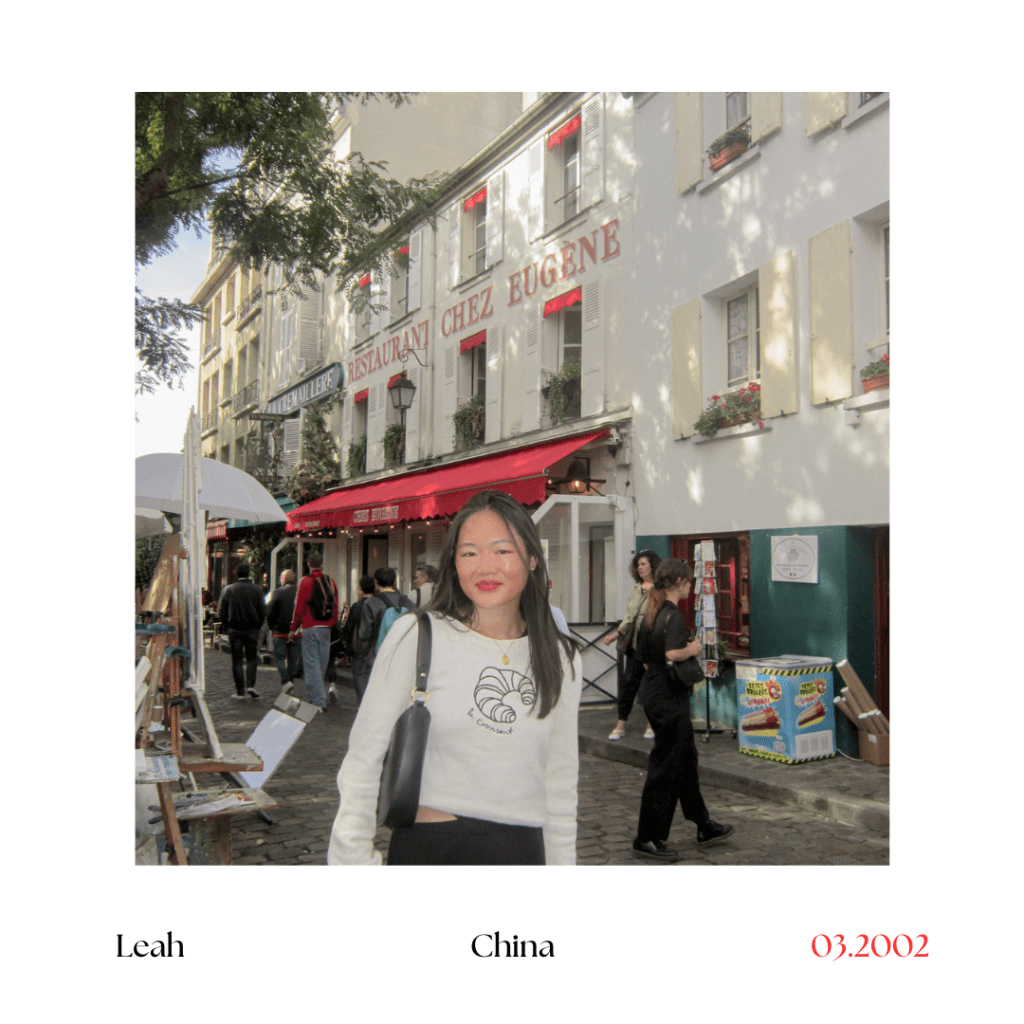

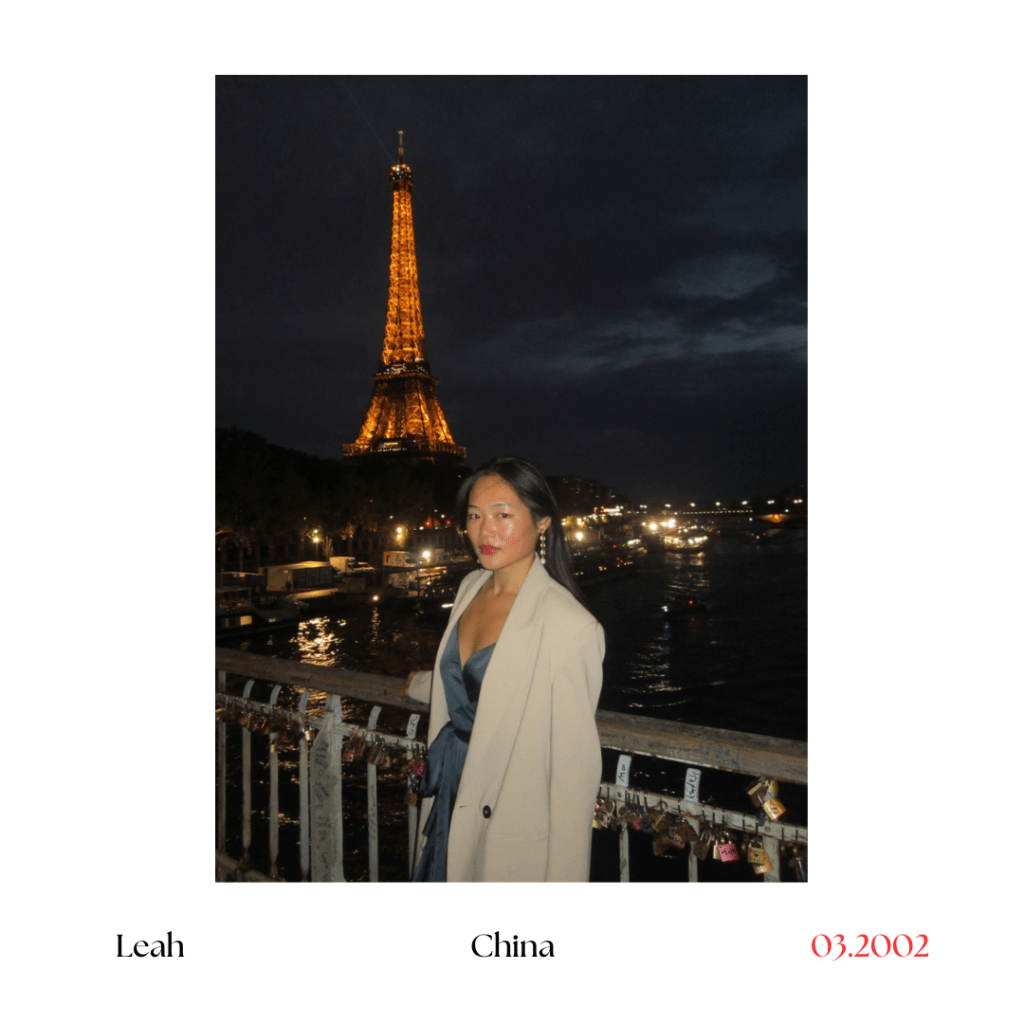

I am extremely grateful for whatever fate there is in the world. I’ve been so lucky in life. I have a loving family and a wonderful mother, and now I’m living in Paris. It’s really a dream life. Having that visual of the orphanage, and knowing that I spent my first year somewhere even more rural, it presents a very clear picture of what my life could have looked like versus what it is now. I truly believe I would have been a completely different person had I not been put up for adoption.

Nicole: Yeah, it’s quite a clear image too. I mean since you and I have been able to visit. It’s wild to think of even being adopted into another family because that could have been very possible or having not been adopted at all and having to stay in the orphanage for longer, it’s quite an intense thought.

How do you feel about adoption as an adult and has your perspective changed over the years?

It’s interesting because last week, there was an announcement that China has closed all international adoptions. So it very much feels like the end of an era.

I’ve always had a very positive outlook on adoption. I grew up with so many international adoptees. From my perspective, all the adopted children I knew seemed very loved by their parents and families, so I never had a reason to think of it negatively. As an adult, my perspective hasn’t changed much. In theory, adoption is a good thing; there are children in need of loving homes and people who want children. Of course, people don’t always do things for the right reasons, and adopted relationships can be dysfunctional in the same way that biologically related families can be dysfunctional. To me, problems seem more related to the individuals and less to the institution of adoption.

I’ve become more aware of people’s misguided perceptions of adoption. As a child, you become accustomed to receiving uninformed comments from other children. Being an adult and seeing comments from other adults who are not part of the adoption community makes me think that a lot of external negativity comes from a place of ignorance.

For example, I have a Barbie that was given to my mom by the White Swan Hotel. They specially-made Barbies that had Chinese babies. The typical Barbie is purposefully childless, but this was a nontraditional portrayal of families and motherhood. After the Barbie movie came out, I went online to see how much it was worth, and I came across a comment from someone criticizing this Barbie for representing a white savior complex. It was so shocking to me that someone had that view of adoption. I don’t understand the assumption that parents can’t love children they didn’t create, and there has to be some ulterior motive. Of course, there are certain specific challenges related to being adopted, but I think people can be too narrow-minded when it comes to the way families are created. I was adopted by a single mom and have a pseudo-dad who is not biologically or legally related to me by any means. Regardless of this nontraditional dynamic, there is so much love, and as long as there is love, what else matters?

Nicole: So, you’ve spoken a lot about your mom and how she supported you over the years. And you mentioned that while you were growing up, she was going to an adoption group. How do you think she, and of course no one is perfect, and she’s tried her best, but how do you think she was able to support you so well?

A lot of parents aren’t as informed as your mom was. And I don’t know if that has to do with location or timing or what it could be, but I haven’t heard a lot of stories where a parent is so open to the conversation, willing to handle that criticism. How do you think she was able to do such an intentional job?

Leah: My mom has always wanted to be a mother, and she reached a point in her life where she didn’t want to wait around for anybody. She was going to make it happen for herself. I think that determination to be a mother is the main reason why she’s such a great one. Of course, some people in her life were skeptical at first, but I think my mom just believed this adoption journey was going to be something special.

From start to finish, the adoption process took 18 months. Knowing my mom, she spent a lot of time planning and researching to ensure she would be the best mother she could be, given the circumstances. It’s just her nature to be intentional, caring, and empathetic.

My mom knew someone who had adopted children from another country, maybe Guatemala. She had asked for advice on interracial/intercultural adoption, and the woman told her the only thing you could do was give them the opportunity to connect with their birth country and expose them to the culture, language, etc. The woman told her that you can’t predict or control how the children will react. You can just give them that opportunity and let them decide how much they want to be connected.

She took that woman’s advice because I definitely had lots of opportunities to connect with Chinese culture over the years. Beyond that, she just has a genuine appreciation for aspects of Chinese culture. The decor in my childhood home is full of Chinese art. Even my grandparents have a room that is Chinese-inspired. So, I always had these environments where I could see the beauty of China on display. My mom was very intentional about making sure Chinese culture had some presence in my life and that it was celebrated. In elementary school, she would come in every year for Chinese New Year and give a class where we would practice Chinese characters, use chopsticks, read stories, etc. I think that was her way of encouraging the people around me to appreciate the culture and maybe make it easier for me.

Once I got to middle school, I started pushing back more on the Chinese lessons and everything else. At that point, she did take a step back and let me decide how much I wanted the culture to be part of my life. I didn’t talk a lot about my complicated feelings toward my race because it was uncomfortable. For the few times I did, I always felt like my mom listened. She wasn’t defensive, which is the most important. She had the ability to distance herself from previous decisions and emotions, and just let me explain why I felt a certain way about things. I appreciate that a lot more now that I’m older and know that not everybody can have that dynamic with their parents.

Do you have any advice for adoptees who have gone through similar experiences to you?

I would say just do things at your own pace. There are so many expectations and perceptions associated with adoption. The way people talk about adoption or the way it’s portrayed in documentaries is so selective. There’s always this story about an adoptee finding their birth parents and having this magical moment.

Unfortunately, it’s not the reality for most people, and it’s also ok if you don’t want it. For a long time, I felt like it was something every adoptee had to do because it was portrayed as the ultimate dream. Then I realized that I am very comfortable with the fantasy story I’ve grown up with of having a loving birth mother who made the ultimate sacrifice because she wanted a better life for me. I know some of the darker truths of Chinese adoption under the one-child policy, and I’d rather be blissfully ignorant about my origin story.

I have this idea that when I die, that’s when I’ll meet my birth mom. I don’t need more than that, and that’s completely okay; it’s in my own right to feel that way, and, you know, not want that biological connection that’s put on a pedestal. I have an amazing adoptive mom, and she is my mother. That’s how I want to live my life.

I think people should do some deep self-reflection and find what is right for themselves. Not just in terms of adoption, but also racial identity, or any other questions or discomforts they may have. Do everything at your own pace and try to find peace. You don’t need to embrace every aspect of your birth country or jump into anything. Simply learning to reconcile with things that have felt like a burden has made a tremendous difference in my life.

If you had asked me to do this interview three years ago, I would not have done it. It would have been way too difficult. Having peace of mind is so important. It’s not an easy place to get to mentally. At the end of the day, you have to be able to live with yourself. Running from aspects of your identity that simply cannot be changed is impossible, and it’s worth it to try to get through it.

Do you have any last thoughts to add?

I don’t know where this fits into the conversation, but talking about adoption has been a rewarding experience. Even though I had adoptee friends growing up, we rarely talked about it. I just wanted our friendship to be based on more than just this commonality. Now, as an adult, I’ve had some great conversations with other adoptees. Even if they don’t end up being friends, that initial conversation can be valuable. It made me feel less alone in my feelings and validated. I think, being older too, we’ve all had time to process how adoption has shaped us. In my experience, people are open to talking about their adoption experience. It’s not something that comes up in everyday conversation, even if certain emotions or burdens associated with being adopted affect you every day. To have an outlet and someone who understands the intricacies can be very mutually beneficial. So great work to you, Nicole, for creating this network for everyone.

Nicole: Thank you. I’m so happy to do it as I reflect on the project I just feel really grateful for the people that I keep getting to meet and the fact that, we just go to this school, that happens to be in Paris and the intention of coming to the school for me has been this project and then presenting and having you share that you’re adopted later with me, that was even, it’s just really wonderful. There are pockets of such lovely connections that have been unveiled to me from this project and I didn’t really expect that. I’m really, really grateful.

Leah: I’ve been in these situations before where I’ve felt very alone, but then I opened myself up in a very public way, and all of a sudden, I had all these people around me saying they’ve been through the exact same thing. It’s crazy what can happen if you allow yourself to be vulnerable and open up. There are communities and connections everywhere. I’m so glad I went up to you after class. I’m such an introvert, so it was very out of character for me, but I was so touched by your project. I love the name so much.

Nicole: Thank you so much. This is all just coming from my brain, so it’s really reassuring and validating to hear other people be receptive towards it and not think it’s way out of correlation to the project. So I’m happy that you like it.

I do! It’s important too. I had children’s books that my mom read to normalize certain aspects of my life. Other than that, there weren’t many people speaking out about adoption or the Asian American experience, etc. More recently, I’m seeing more Asians in the media and more adoptees speaking about their experiences. I wish I had these when I was younger to help me work through some of the challenges instead of feeling like this little genetic island.

Nicole: I think that’s my new favorite phrase, genetic island. I really relate to that too. Like my motivation in my life, at least at this period of time, is to be the person I needed when I was younger.

I know this is a super niche region to be on Instagram, but if somehow, and I more mean like middle school. Nicole. I know Instagram didn’t even exist. Whatever. If I somehow stumbled on someone’s story and I heard that they were adopted and they weren’t just talking about meeting their birth families, but more like, and obviously some of this would have gone right over my head, as a 12 year old. But I would have been so refreshed to know that there’s another side of even the conversation of birth mother birth father searching that felt like the crux or the pinnacle of adoption to me. That felt like the ultimate reason I’m alive is to figure that out. And that was just really difficult because when I would think about it, I was like, well, what if she says no and even that thought just sends like, a huge vibration through your body? Like, oh my God. I didn’t know that was possible, especially when I was a child. Yeah, if I would have stumbled on something like this, I just know a part of someone’s story would have touched me, like in some way, I just know it. I know it.

Leah: Yeah, I agree. I love that you focus on the real everyday issues that adoptees face. Even just speaking to you, I’ve learned about so many different experiences and possibilities I wasn’t even aware of. To be quite honest with you, it’s made me more grateful for my mom and how I was raised. Demystifying this fantasy of how the adoption cycle is supposed to go and what your story should look like is very powerful.

Nicole: Thank you! Story by story.