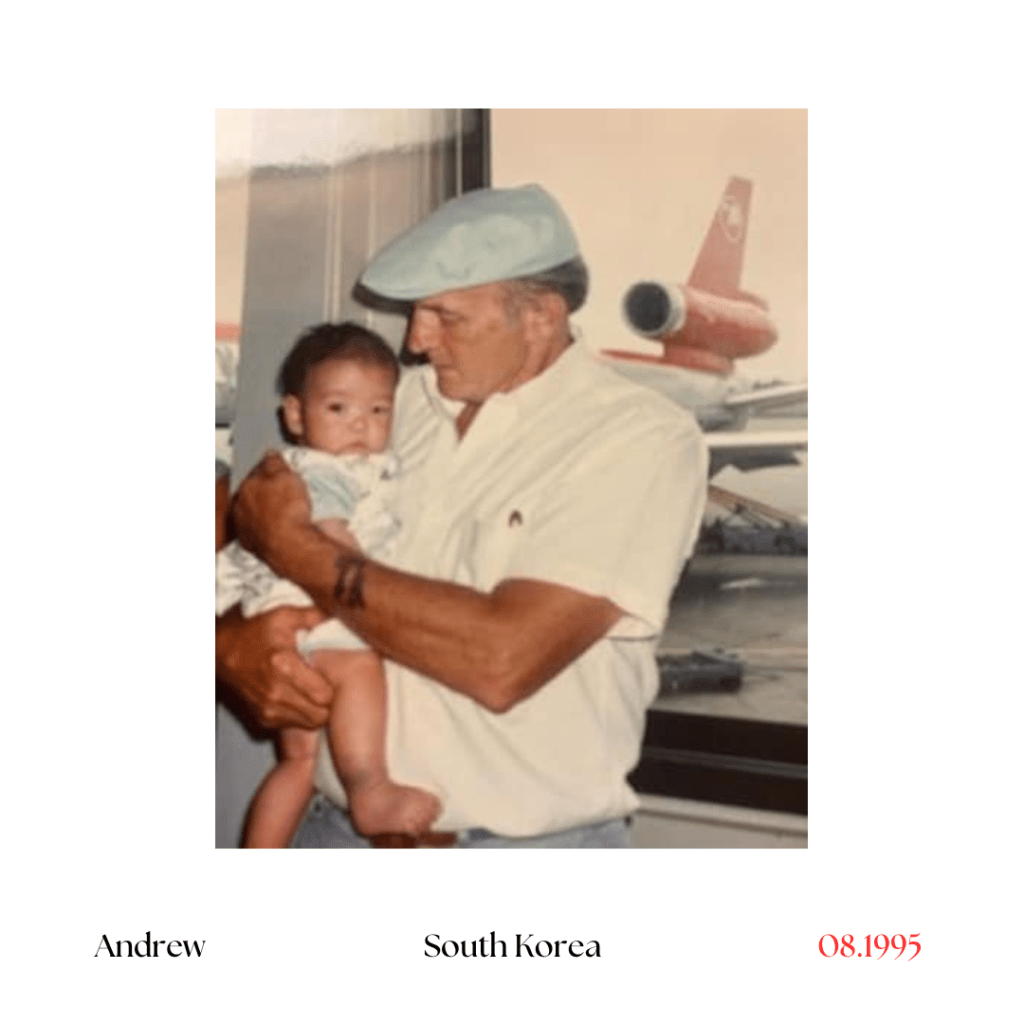

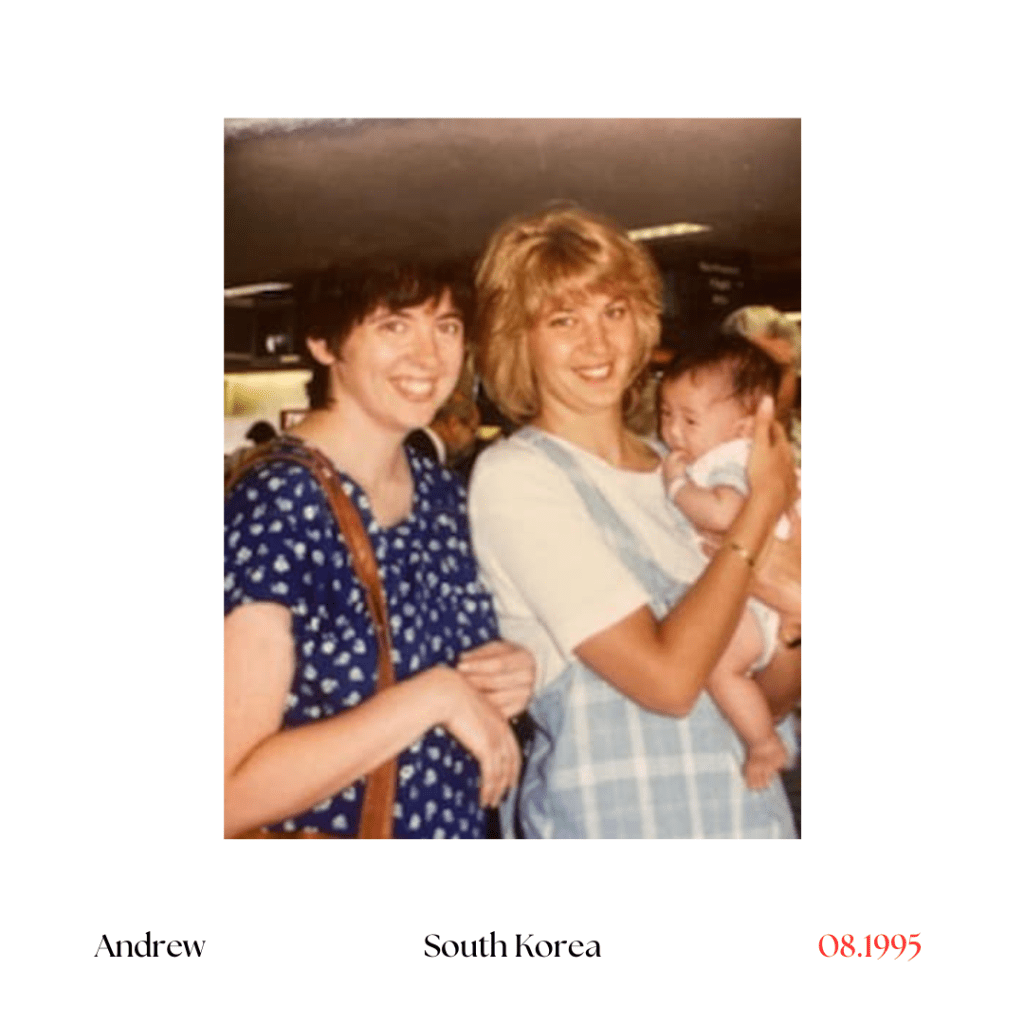

My name is Andrew. Biologically, I was Chan Lee for the first six months of my life. I grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota and I’ve spent most of my life here. I was six months old when I was adopted. The one pager that I have of my adoption is that the hospital says that I was born in Busan at a small hospital called Koo Hoo Hospital to parents who weren’t married. My mother was supposedly a barista and my dad was a traveling businessman of some kind. And as far as I know, I was left at the doorstep of an orphanage in Busan and adopted by Polish and German parents when I was about six months old.

I think adoption, and my view and how the chaos of the universe has ended up with me getting to live this life has changed a lot with my maturation as a human person.

When I was younger, it wasn’t something that I thought about a lot, but I went to Catholic school growing up and I was often one of the few people of color, and it didn’t really bother me until I was a teenager and I started to have more identity problems.

Thankfully, when I was young I had the experience of going to a summer camp called Korean culture camp to feel somewhat represented, but I didn’t really know what that meant. Even as a kid it felt important, just knowing there’s other Asian people around me who aren’t Vietnamese or Hmong, which make up most of the Asian population in the Twin Cities.

But then as I got into high school and started having just general questions about my own identity as a person, my identity as an adoptee started to come a little bit more to the forefront. Who am I? I’ve had so many situations where I’m maybe a little too white or American for the Asian kids or a little too Asian for the white kids. When I was growing up, my mom would make Korean food, she would make bulgogi and mandu to try to help me and my sister. It was symbolic of kind of reaching towards what our identity meant to us.

At the same time, I grew up playing hockey because I had an uncle who was an accomplished hockey player, and I thought that was important. I didn’t get the Polish and German genes, unfortunately, I’m a 5 ‘7 Asian man. I’m not a six foot four Polish man. So, I was kind of in between things for a long time. And through some of those identity issues to which at one point in my later high school years was really bothering me and was the cause of some anxiety I discovered a deep love for music and now that’s what I work in full time.

So I’ve had a good place to funnel a lot of those emotions and funnel a lot of the negative and the positive feelings about adoption and what it means to me.

I think the Asian American adoption story is very different from the Black American experience or other immigrant stories to where ours is really nuanced and doesn’t necessarily have a lot of representation in media and doesn’t just have a lot of representation just around. Even going to Korean restaurants usually in most major cities is going to get Korean BBQ. But, where can you go to get traditional Korean food or find traditional Korean items at markets? It’s really hard to find that.

There’s a market on Snelling Ave in Saint Paul called Kim’s Convenience Store, and I’ll go there to get groceries half the time because it’s cheap and convenient, but also, it’s a Korean grocery store. And sometimes when I go there and most recently, I had the experience where there were multiple Korean people there who I believe immigrated from Korea and now live in Minnesota, who were speaking Korean in the store. And as I was walking around, I kind of had this moment where I was like, I look like you, blood wise we share the same blood. Who knows maybe we even have relatives in common, but I have no metric for relating to you on that level other than by the shallow physical version of myself.

When it comes to who you are, your identity as a Korean, ours is completely, completely different, and one that I’ve tried to make sense of but still don’t have a full understanding of, but that’s more exciting to me than depressing. Like an opportunity maybe to find out more about who the hell I am? Rather than something that has to make me feel bad about myself and my upbringing.

I feel like I’ve been very lucky in that my life I’ve lived a very blessed life. But to understand and learn more about my Korean heritage is something that I think would offer me a lot of closure foundationally.

Nicole: Have you ever been back to Korea?

Andrew: I haven’t, but next year my sister and I, who is also a Korean adoptee. She graduated from school two years ago, and my graduation present to her is a plane ticket to Korea for the both of us. So next year, 2025, we’re planning on going at some point for the first time, both of us back to the motherland. I cannot wait.

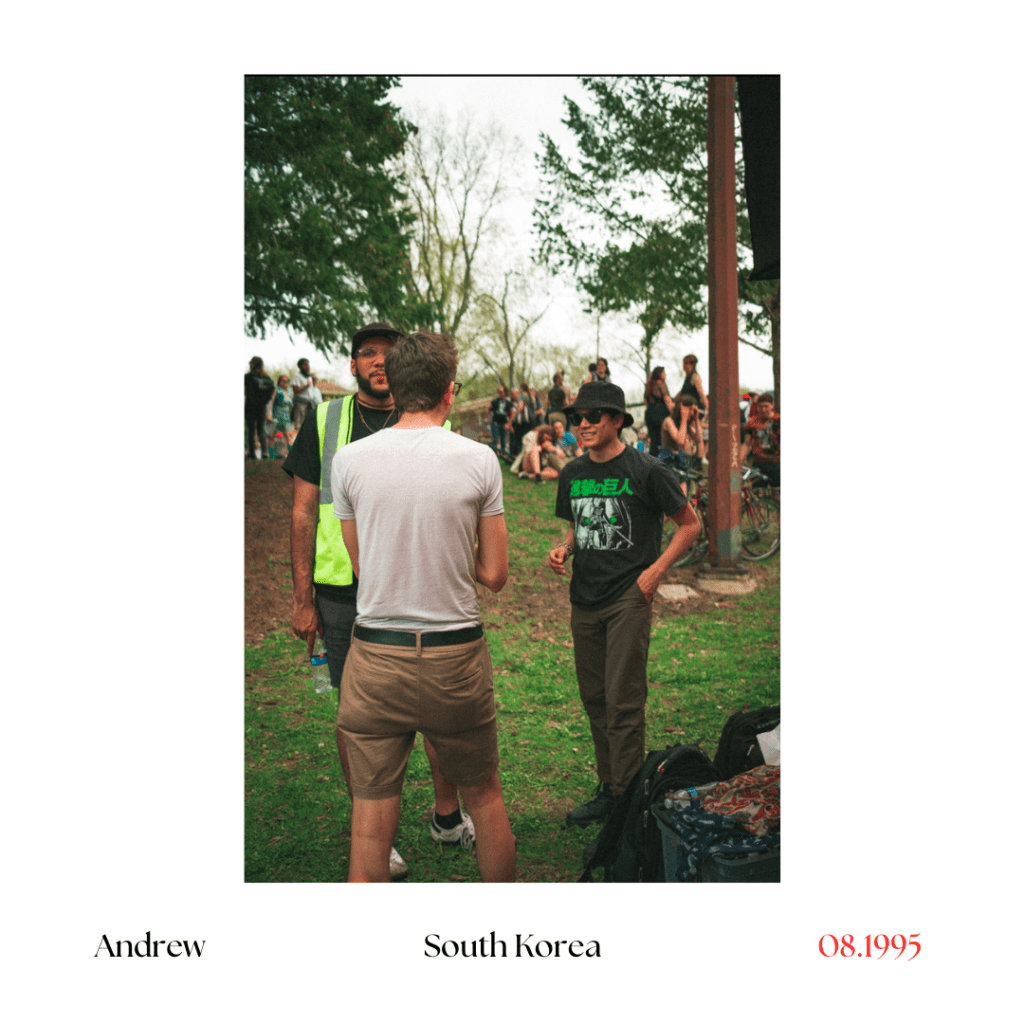

It should be really exciting, and I’ve been on a journey of trying to make contact with a biological relative over the past few years. I’ve been unsuccessful so far. I went through the Eastern Social Welfare Service, and it felt like more or less hiring like a glorified private investigator. I wasn’t able to get a ton of information through them, so there’s an Adoptee Network here in Minnesota that I’ve been going through to try to understand how people have made contact through social media and through other avenues. I forget what it’s called, it’s like the Korean adoptee friends and fam group or something. But it’s like a Midwest Group on Facebook.

But I made some connections there. One of the guys who runs this group hosts events around Saint Paul/Minneapolis. I haven’t been to one yet, but I would like to at some point. So, there’s those resources.

Nicole: Have you ever done 23andMe or ancestry or have any interest?

Yeah, that’s the other angle. I’ve done both of them and it’s funny, the first thing they tell you is your genetic makeup, and when I received that back, it said you’re 100% Korean and I was like, okay, now I know for sure, good.

I’ve done both 23andMe and ancestry. I found that between the platforms I have like 25 plus DNA relatives on both. But I share less than .5% DNA with them, so the closest relative that I’ve encountered is like 4 generations ago our grandparents are the same people, or something like that. Our grandparents from around the 1850s or probably older than that were the same people. So, we have some family tree lineage, but other than that I’ve never made contact with a serious close relative like a brother, sister, mom or dad.

I would like to, but it’s not something I’m banking on because there’s such a scope in people’s mindset about meeting biological relatives, but also their experiences. I know people who have gotten in contact, gone to Korea and then been stood up by the family member that they were going to meet, probably because of a lot of guilt and shame on their end.

Nicole: Exactly and you have to have patience for that. That’s part of the nuance of being an adoptee: we have to be the ones to make sense of the unknown, and that can be a really tough place to be. To find comfort, and to potentially never have those questions answered is hard.

I’ve never met my biological family either, and I went through Children’s Home to go through Eastern Social Welfare Society, but never have found anything super concrete and all I want is a picture. So, finding peace with not knowing is probably one of the most challenging parts.

Andrew: That’s a good point and I think in a way it is that way for me too, because ultimately getting closure on something is work that’s twofold and requires a two-way street of communication to bridge the gap of whatever problem you’re going through.

And for this, which is a lifelong plight, is the wrong word. Quest! Quest, that adds a little bit of excitement to it, but a lifelong quest of self-actualization.

Many people, I think will not, and I don’t know what the statistics are of how many people have actually met a biological relative, but I assume most will never get that full closure of being able to do that. So, you do the work yourself.

And for me, I did the failed athlete to musician pipeline to a tee but that’s been a way for me to funnel my creative and emotional energy. And dealing with my identity of being a person of color around mostly Caucasian people growing up and I’ve probably gotten good at small talk and being friendly to everybody through that just so I could feel like I’m relating to people. So it’s all of those things and I feel very blessed that I’ve had good friends around me and a family who has been very supportive of my journey with it so that I don’t feel alone because it’s even worse to feel alone.

Thankfully, I haven’t felt very alone throughout most of this journey, which I think has been a blessing for me. You gotta do a lot of the healing on your own when it comes to closure.

Nicole: Yeah, right? And I guess if you look at any personal problem, it’s a human issue not knowing something about your life and not just an adoptee issue, it’s just a part of life. But I think with adoptees, and I can’t speak for everyone, and I don’t want to, but I would say predominantly from the conversations that I’ve had, it’s on us to deal with it. We have to confront that fact earlier than other people. Like I remember having questions when I was younger, those are some of my first memories. You know what I mean? But when I would bring those questions up, it must be hard on our parents too to not to have the answers, you know?

Andrew: Yeah, absolutely. I mean because I don’t know how much research my parents actually did into Korean culture or whatever, but I grew up a Midwestern kid. I didn’t grow up a Korean kid at all. Other than my mom making bulgogi on my birthday or my gotcha day or something.

Nicole: Do you celebrate it?

Andrew: Yeah, I do. It’s August 7th.

Nicole: Mines, August 8th!

Andrew: Ohh my gosh. So many webs connecting the two of us today, that’s really funny. We still celebrate it.

But I grew up a Midwest kid. I’m lucky to have a Korean adoptee sister too. We’re not biologically related, but I think in a way that makes us even stronger that we have a bond in a different way that goes beyond blood.

I’m lucky to have had her, but at the same time, most of me finding out the Korean part of my identity has been in my 20s when I’m a little more of a self-actualized person, wanting to understand and can put aside maybe some emotional parts of that journey that I didn’t understand that I can now funnel into research or just a more full wider scope, 30,000 foot view rather than just making it about me. Maybe my greater place in the place of all the people I’ve met who have a journey similar to this and finding out just what it means, not making it about myself, but also learning about myself through it, I guess.

Nicole: Yeah, it’s zooming out to zoom in.

Andrew: Exactly zooming out to zooming in.

Nicole: That’s like my favorite thing to say because it doesn’t feel so personal. Even conversations like these, it’s so helpful to know that you’re not the only one who’s gone through it and you’re not alone in that. It’s so nice. I think that’s why Korean Culture Camp felt so natural because we didn’t even talk about the issues of being adopted.

Nicole: So, you’ve talked a little bit about music and how your creative pursuits have helped you express some of your emotions. Can you talk a bit more about your music?

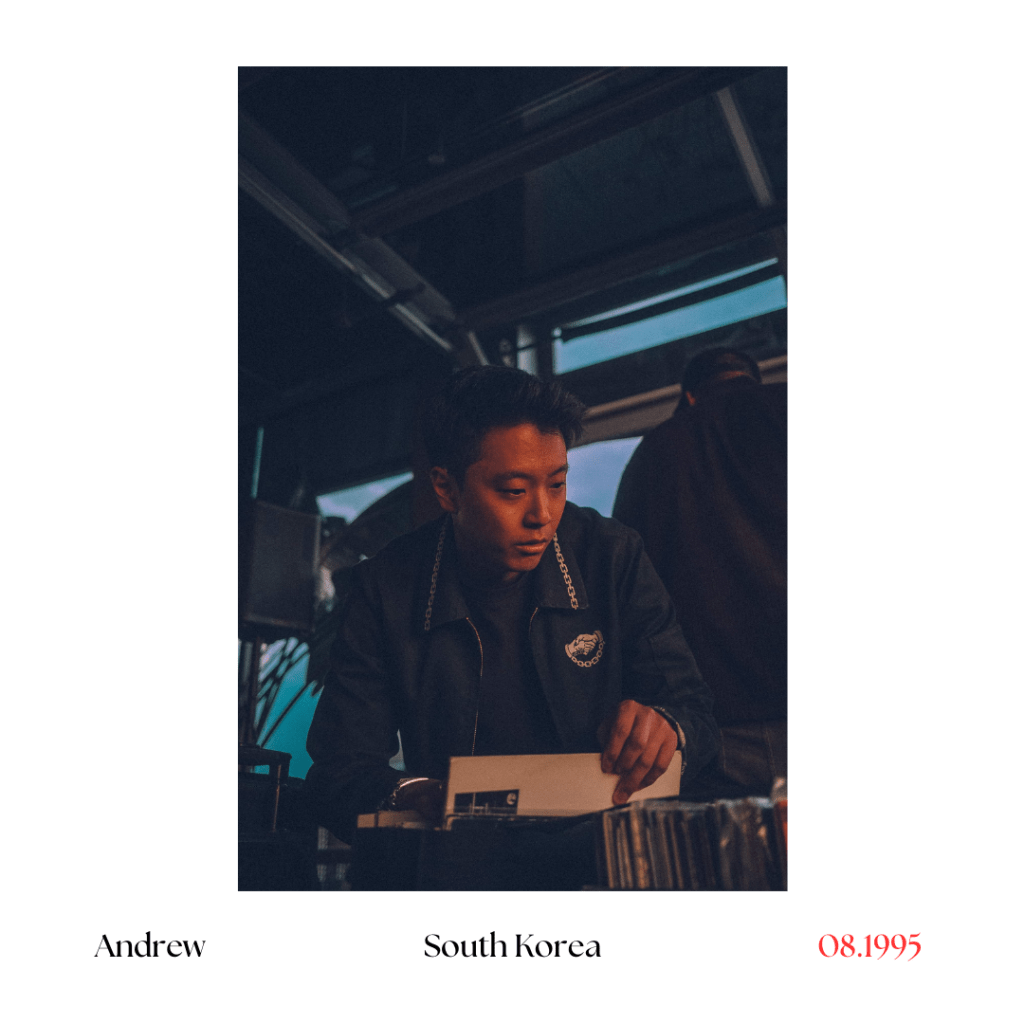

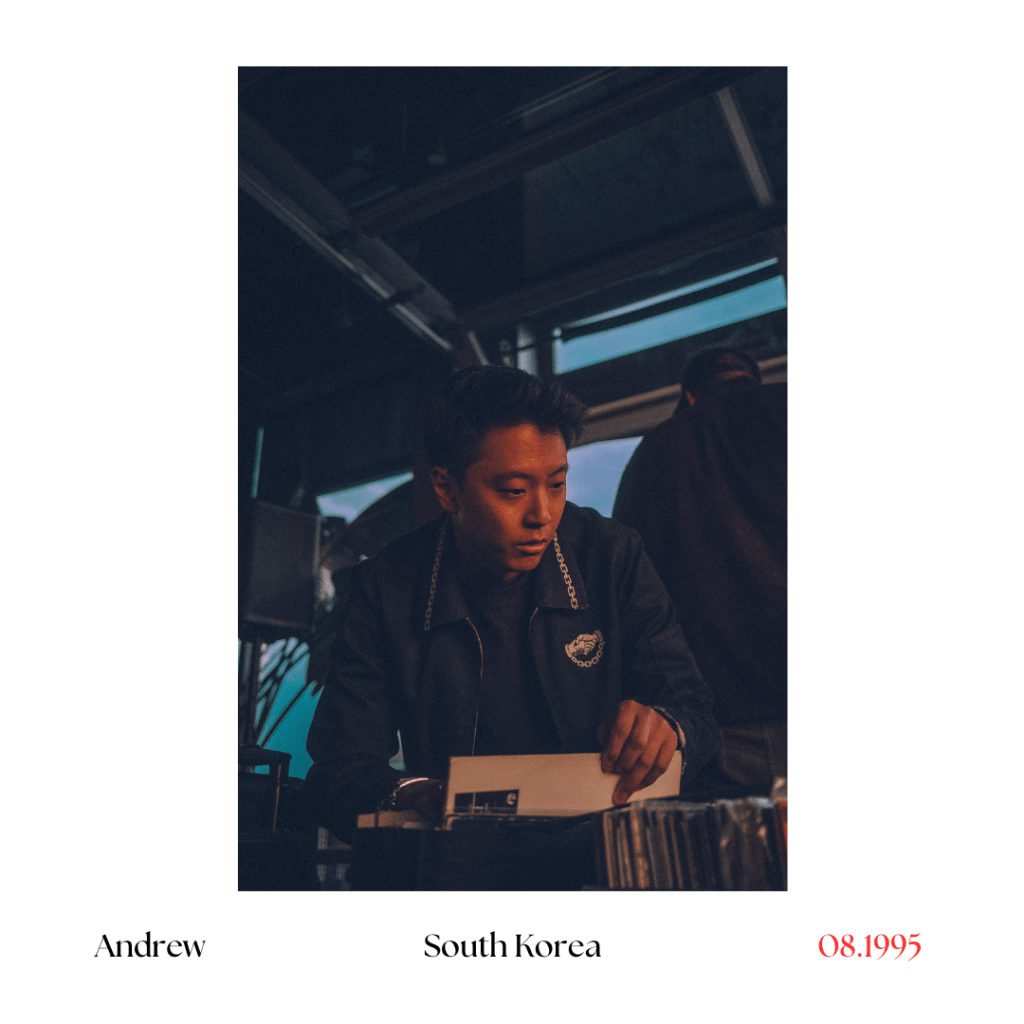

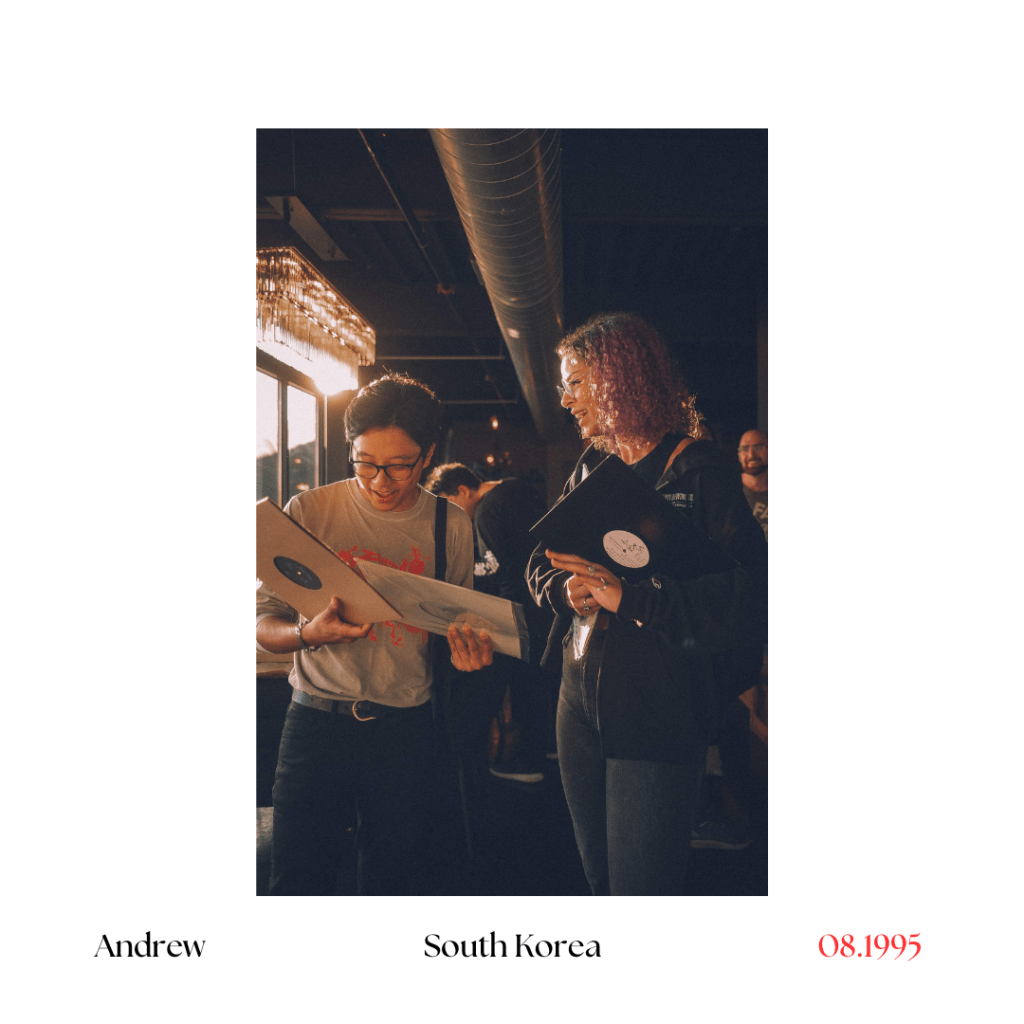

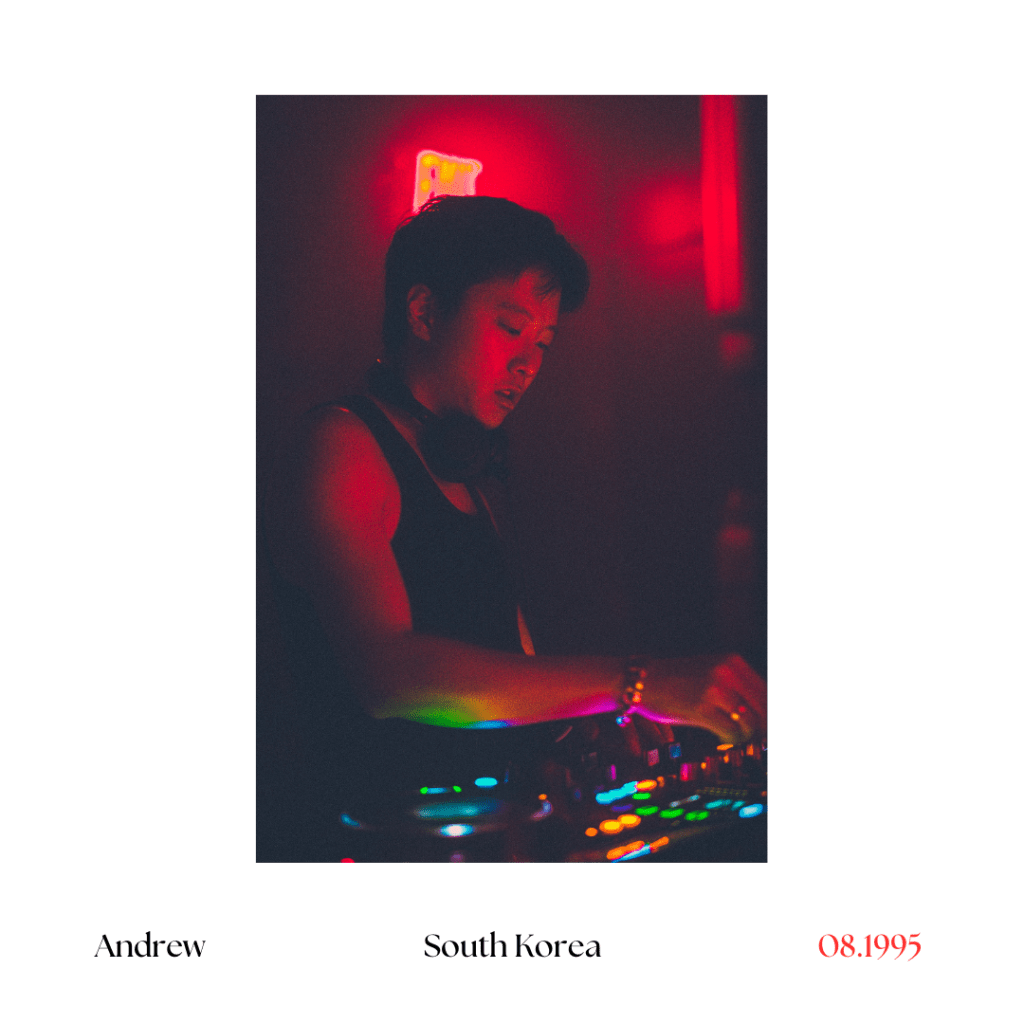

Yeah, I grew up a classically trained pianist and guitarist. And in more recent years, I’ve found dance music. I lived in London for two years and I worked for a music technology company while I was out there. And I was really exposed to sort of the more underground dance music versions of EDM. And those spaces in communities they’re kind of built on black queer culture in Chicago and Detroit, house music in particular.

And oftentimes, those dance floors are very inclusive spaces. They’re very safe spaces and as someone who has gone through a lot of identity issues, it was some of the first times that I have been to an experience like that. Listening to DJ’s and stuff and being on a dance floor where I didn’t have to, I didn’t feel perceived or that people were watching me, and it felt comfortable and that I could just be kind of one with this experience.

And so I’ve in the past ten years I’ve been actively gigging as a guitarist and DJ. And through that time the people that I’ve met in the community are some of the people who I’ve been able to connect to in a way that has helped me with my own identity, talking with people who go through gender identity issues and learning that maybe that’s weirdly not so different from my race identity issues and my cultural identity issues talking with people who come from all sorts of different backgrounds of life, even talking to my black American friends or Latino American friends has been eye opening for me. Because it’s like zooming out to zoom in, there’s a lot of people who have similar issues sometimes not even related to race or culture directly. Maybe it’s their sexuality or their gender identity, or something else, but it’s still a similar problem, and I think it’s about how do you actualize yourself? How do you become more human and be as honest as you can about what that means to you?

So those scenarios and those friendships that I’ve made through the dance music community have been some of the best moments where I’ve been able to deal with some of my identity issues as a Korean American too, oddly enough.

Nicole: That’s wonderful to find that sense of community. And so do you create your own music and everything?

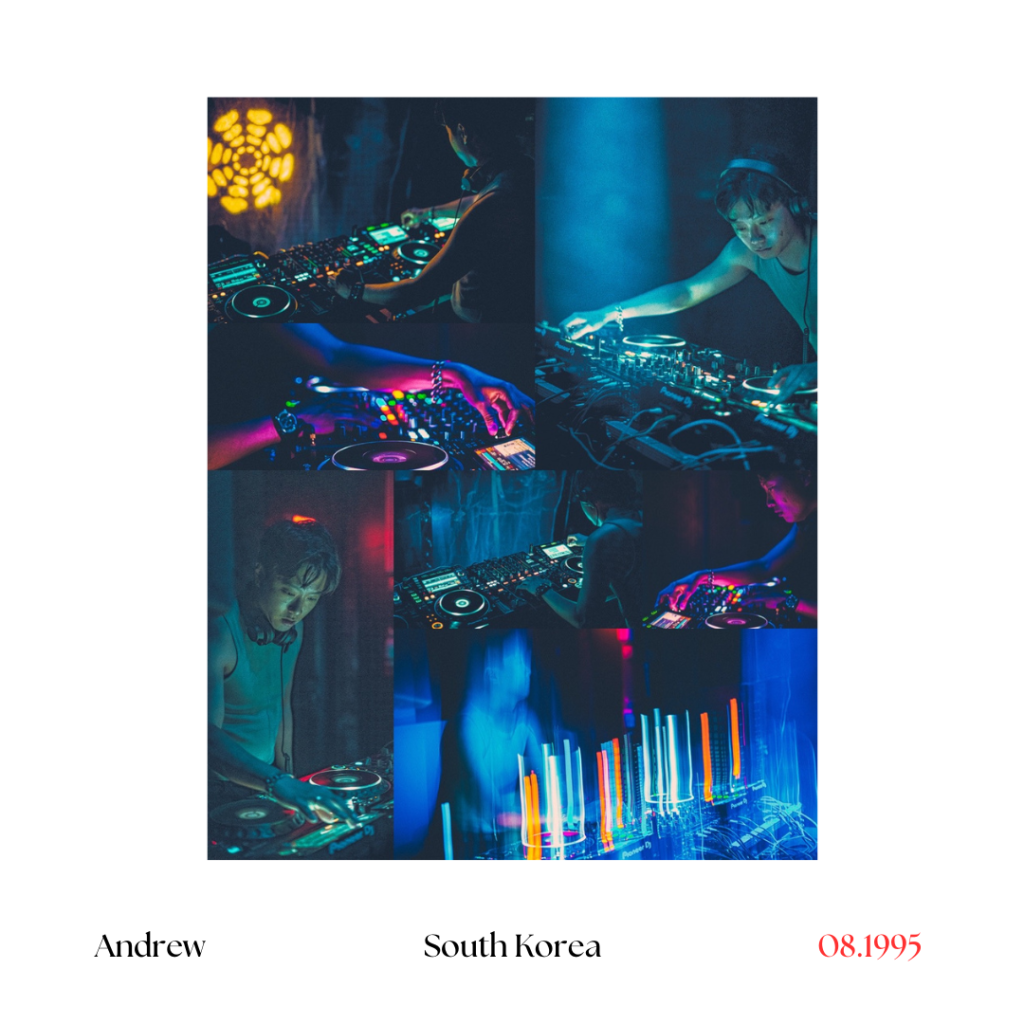

Andrew: Yeah, so I do some commercial production where I make music for TV shows, commercials, stuff like that, video content. But then I produce under the moniker AKKO as a DJ and music producer. So I’ve made a lot of hip hop music over the years, but more recently I’ve found a deep love for dance music, house music, techno, music, and many of the club sounds that are coming out of the UK and amazing artists and people around Europe too.

Nicole: So, when you’re writing or producing music and everything, where do you gain inspiration from? What inspires you?

Andrew: A lot of my inspiration lately kind of comes from the mundanity of being able to do it. I’m a fairly good musician and producer now and it’s kind of one of those things where I can get into that state of flow into, that ikigai, that Japanese term to where I can sort of turn my brain off and be here now it’s like the most in the moment I ever feel in my life, to where I can just kind of let it come out of me and sometimes there’s an emotional attachment there that I think wants to come out. But oftentimes it’s a case of, okay I am here intentionally now engaging in this activity, this creative export and manifestation of who I am and if it becomes something great, but I don’t put pressure on it to have to be this or have to be that or live up to a certain moment.

And now that I’m saying this, maybe that’s also kind of a mirror of what I’m trying to tell myself too, that I don’t need to live up to certain moments or put too much stock into being this or that. Because getting to that place where I can just kind of shut my brain off and just be is a really nice thing to quiet the voices, the horrors. *jokes lol

So yeah, I’ve been making music for a long time. It’s a vocational passion for me. In my life, I don’t think I’ll ever not be doing it to some degree.

Nicole: How do you think your creative expression with your music relates to your identity as an adoptee?

Andrew: That’s a really good question. A lot of the music that I perform as a DJ does not necessarily belong to me culturally, in a way, I play music from a lot of that that was built on the backs of black American culture, or Latin American culture. I do play music and share music that comes from Korean artists and ideas from Korean artists, but a lot of times that’s not necessarily the case and into my own productions too, where I’ve been very inspired by hip hop and punk music, especially in my earlier years. None of that belongs to Korean American Adoptees or Asian America, and in general. But the people that I’ve met who are carrying these genres on their backs too and bringing them into the future and modernizing a lot of these sounds have been so open about sharing that with me because it’s important to represent yourself in a way that feels reasonable.

And when I work with Latino artists or black artists, and we’re able to create connections there and share some of these stories and I think it helps me getting a better understanding of myself as an artist and understanding myself as an artist, is understanding, Andrew, the human being, which is understanding my adoption story in a way.

I think that web is probably more of a long web. It’s a long chain of things to get to that point of my adoptee story, but ultimately, I, you know, any artistic pursuit I think is a journey of self-actualization. There’s me using that term again, but all of that kind of funnels in and I was a very emotional teenager and an emotional kid and kind of a softie. And I think finding this musical and creative work has helped me funnel in very positive ways that I probably would have done so healthily had I not had this.

So it’s made me who I am.

Nicole: I feel like it’s all connected because identity has so much to do with self-worth. And if you’re funneling a lot of your emotions into something you’re passionate about, like while you’re in those trance states, or when you’re creating things, you are allowing your entity to breathe, do you know what I’m saying? So, you’re not putting yourself in any sort of box.

And I think that is something that anyone can do, but with people of color especially, if you’re spending a lot of time with people who don’t look like you, Caucasian people in our experience, it’s easy to feel the pressure of being different than the stereotype, you know? So when you’re allowing yourself to just be completely as you are, I think that is a wonderful place to be.

Andrew: It is. And I think every Asian American Adoptee has probably felt some imposter syndrome at some point. I felt like I’m cosplaying as an Asian person.

Nicole: Absolutely. Banana. Hahaha golden oreo.

Andrew: Yeah, haha. I went to work for a company based in Shanghai about five years ago. That was my first time being an Asian American in Asia. It was such an odd experience, and I’ve never felt more like a banana. A Chinese person would hear 1 syllable out of my mouth and be like, okay, I get what’s going on here. And those types of things are much different than being around white people or I guess specifically in Minnesota, Vietnamese or Hmong people, it would feel much different than being in Shanghai and actually being in Asia. Those situations used to hurt me a lot more when I didn’t know myself better.

I think it’s kind of a blessing to have aged a little bit and matured and to know that most of these identity things, it’s a fact of life that’s unavoidable, but it’s also a blessing to be able to be on a journey of self-discovery because we don’t have the blessing to just not have any questions. There’s so much unanswered for everybody.

There’s so much unanswered, and the luxury of not having those questions is lost on us. I actually think it’s probably one of the most Korean things about Korean adoptees is that generally Korea is known as a country who had to look forward and be very future thinking as just an economy and a culture that works really hard and asks a lot of questions. And adoptees sort of have to do that to find out who we are, in a way.

But again, I don’t shy away from that anymore. I find it to be a blessing to learn about myself and to be interested and to have those questions to know myself deeper.

Nicole: Yeah, for sure. I’ve never thought about it like that, but I like how you put that.

Andrew: Optimism, baby.

It can be a lot, but if you don’t put too much pressure on yourself, it doesn’t have to feel like a lot.

And I’ve felt every single emotion about being an adoptee from shame and guilt and self-worth, self-hatred, to feeling really good and feeling very proud of myself and who I am to be this kind of mutt of a guy raised by white parents and born in Korea, but doesn’t even look like half the people I’m around half the time.

But if you don’t put too much pressure on the negative side of that, it is a beautiful thing to be an amalgamation of so much and to try to understand that all is a blessing and not a detriment to who you are as an adoptee.

Nicole: Well it makes me think of the realization that I’ve had recently the depth of shitty feelings that I felt about being adopted matches the height of the highs. And because of the scope of feelings we felt, think of how much more space we have to connect with other people. Hence you talking about connecting with a range of people, no our experiences are not exactly the same, but loss and pain are part of the human experience. We have felt that.

Andrew: Me too. It can only be appreciated in hindsight, I think. But what a joy to experience all of the emotions that can happen to a human being during our lives. It’s a little heady, but I think of the scope of this conversation. But you kind of have to feel that way a little bit, so as not to feel shitty about it all.

As an adult, I have a very positive view of adoption in general, not just limited to our Korean American experience, but adoption in general. If I wasn’t adopted, who knows what would have happened to me. But somehow, in the chaos of the universe, I was adopted by parents who have absolutely loved the hell out of me and have given me so much opportunity and still support me to this day, in so many ways and love me and that is so amazing. And there are a lot of realities where that doesn’t happen to me, I think.

I have a very positive view of adoption in general because I had a great experience. I know not everybody else does, but it’s great and as I’ve gotten older, my view of my individual self as an adoptee has changed, along with the maturation of myself and growing up.

I was a very emotional kid in high school and had a lot of identity issues that I funneled through music and was able to funnel through having good friends too, and thankfully my little sister as well we’ve always been able to confide in each other. Just a huge blessing there. Shout out to Amy. What a beautiful person. She’s getting married in two weeks.

Anyways, identity issues through high school and my teenage years being able to be funneled in through music and finding myself in my 20s has been a big era of my life of maturing, knowing who, and finding out who I really am and then being sort of comfortable with all of the things around me. Just practicing contentment and gratitude. And not feeling like I have to put a bunch of pressure on answering certain questions or manifesting a certain view of myself. I think everybody in life has to wear multiple masks every day. You gotta be Andrew, the son, Andrew, the brother, Andrew, the coworker, Andrew, the artist, Andrew, the Korean American.

But all of that is good and all of that is part of this adoptee story, and as I think about this, the adoptee story being foundational to all of the good things and bad things that have happened in my life and everything in between, it all kind of funnels down to that, what a blessing that I get to live this life because there’s a lot of realities where that doesn’t happen.

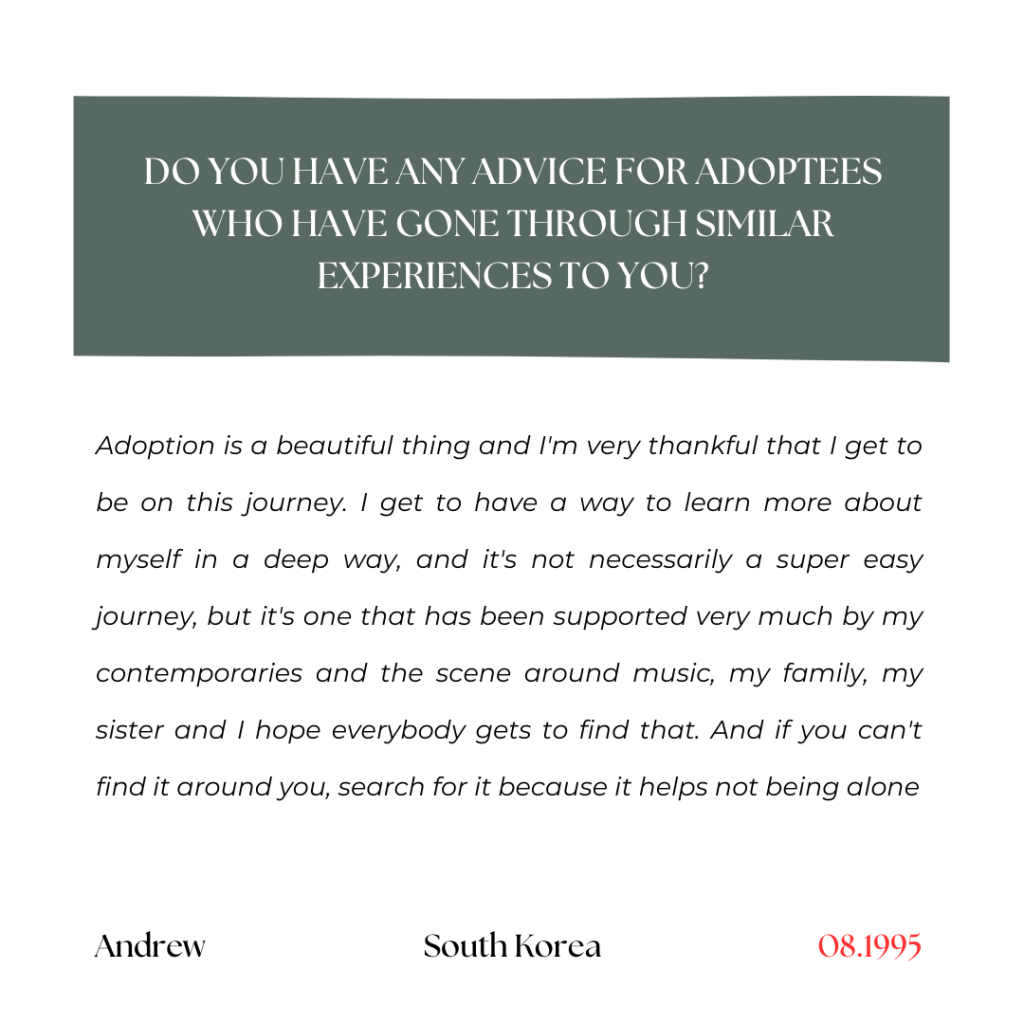

Do you have any advice for adoptees who have gone through similar experiences to you?

Yes. If my advice was going to be based on the stuff that has sort of hurt me or has held me back through adoption, I think I alluded to this a little earlier, but don’t put too much pressure on yourself if you can avoid it. This journey as an adoptee and the amount of questions and the amount of self-actualizing you actually have to do to be somewhat comfortable with it. And once you start thinking about it too much it can be daunting, and it can feel really bad and really extremely uncomfortable in a nuanced way that people around you almost surely will not understand.

And if you put pressure on yourself to understand that or get answers quickly, you could get answers that aren’t actually reflective of your truth and are shallow, which has happened to me that don’t actually help you get anywhere. But two, can just end up hurting you more.

What has helped me have a better view of myself over the years has been slowing down, thinking about what I really need as a person and then through that, seeing if that somehow funnels into my adoption journey and not necessarily making my whole life based on that. I don’t think necessarily all of us do that, but I did for a while and it took me a while to get from point A to B to say that I can go through the journey and learn about myself and these deep things that are scary questions with scary answers, but I can do this right because I’m not putting pressure on myself to get something out of it.

Because you can make contact with a biological parent and then never be able to see them because of their own world of shame and guilt and suffering. But if you go on this journey of discovering who you are as an adoptee, whether that’s trying to find biological relatives or putting yourself out there in adoptee communities. I think doing it in a way where you’re just being yourself and not putting so much pressure on this. “I have to be this adoptee, and I have to get these answers”, but more just to be there and be represented and comfortable. You’ll get so much more out of that, and it took me a while to get to that point.

Adoption is a beautiful thing and I’m very thankful that I get to be on this journey. I get to have a way to learn more about myself in a deep way, and it’s not necessarily a super easy journey, but it’s one that has been supported very much by my contemporaries and the scene around music, my family, my sister and I hope everybody gets to find that. And if you can’t find it around you, search for it because it helps not being alone