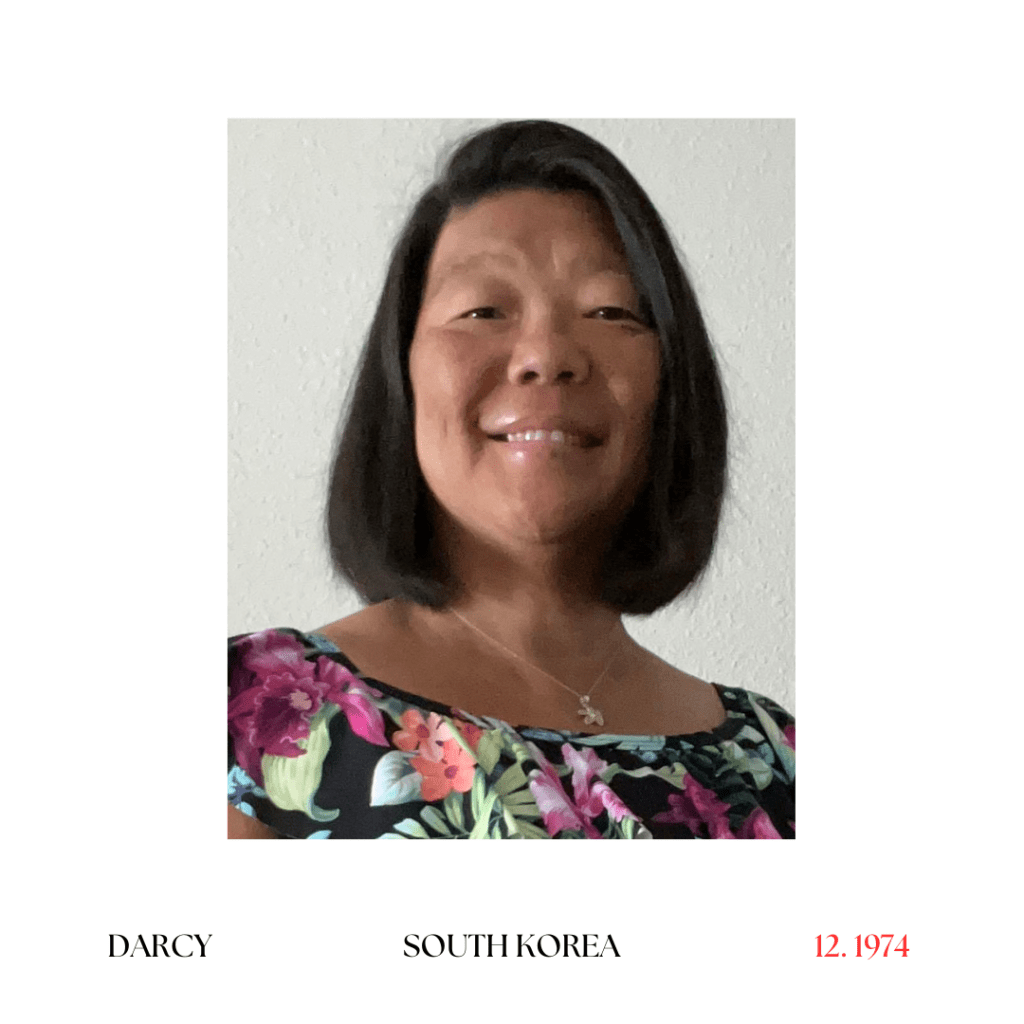

My name is Darcy, and my Korean name is Lee Bok Shil, which I understand the orphanage had named me. I grew up in rural Nebraska, outside of Albion. I live between Austin and San Antonio in New Braunfels, TX.

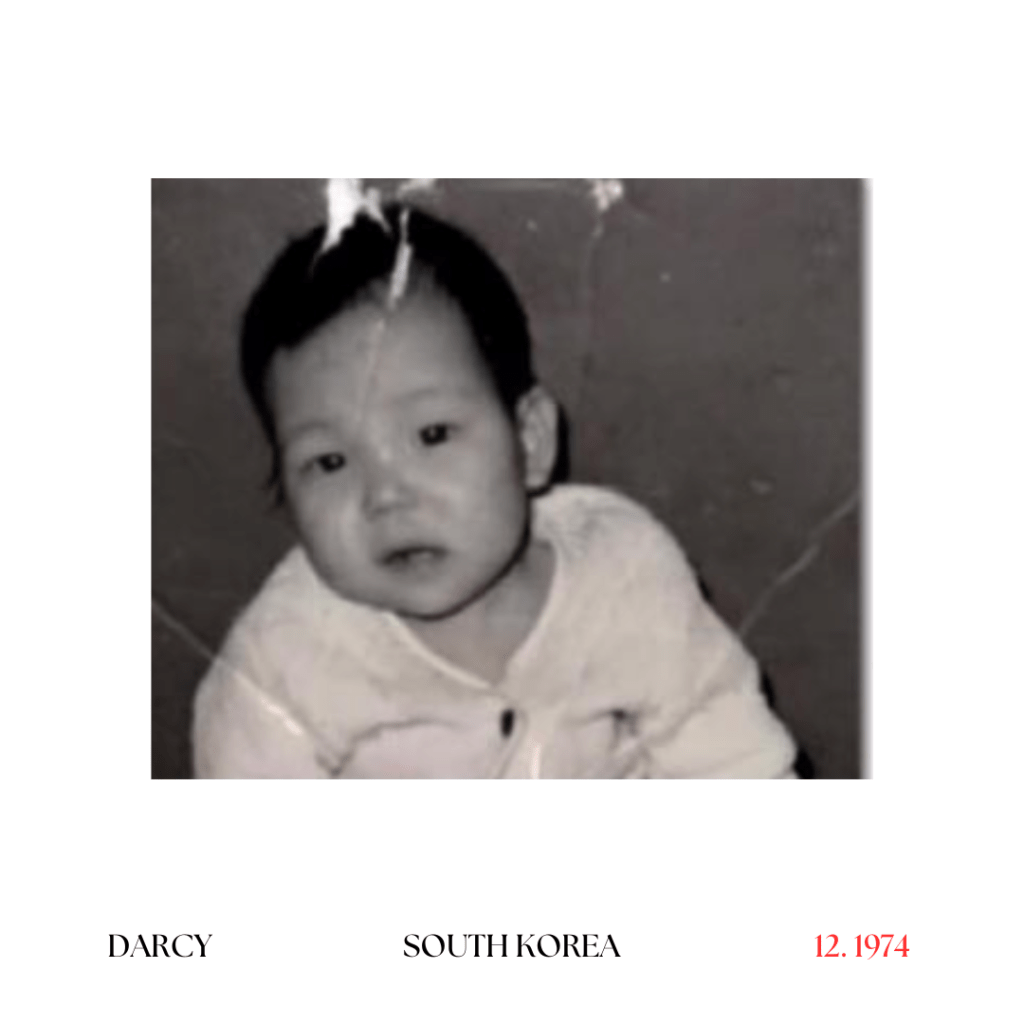

I was two years old and adopted by Eastern Social Welfare Society. My American Adoption agency is Dillon International Incorporated. However, at the time, it was called David Livingstone. So, the name changed soon after the adoption agency got up and running.

David Livingstone began in 1972 with the cofounders Jerry and Deniese Dillon. Within a couple of years, they changed it to Dillon International, branching out to offer adoptions in other countries. Unfortunately, Dillon International closed its doors about a year ago. However, they continue to help with post-adoption services as much as they can by sending people to different agencies that can help them.

People have said this to me, and I have now come to believe it as well, I consider myself a resilient adoptee. Growing up, I did not know much about my adoption or my adoption story, let alone even learning about my heritage or culture.

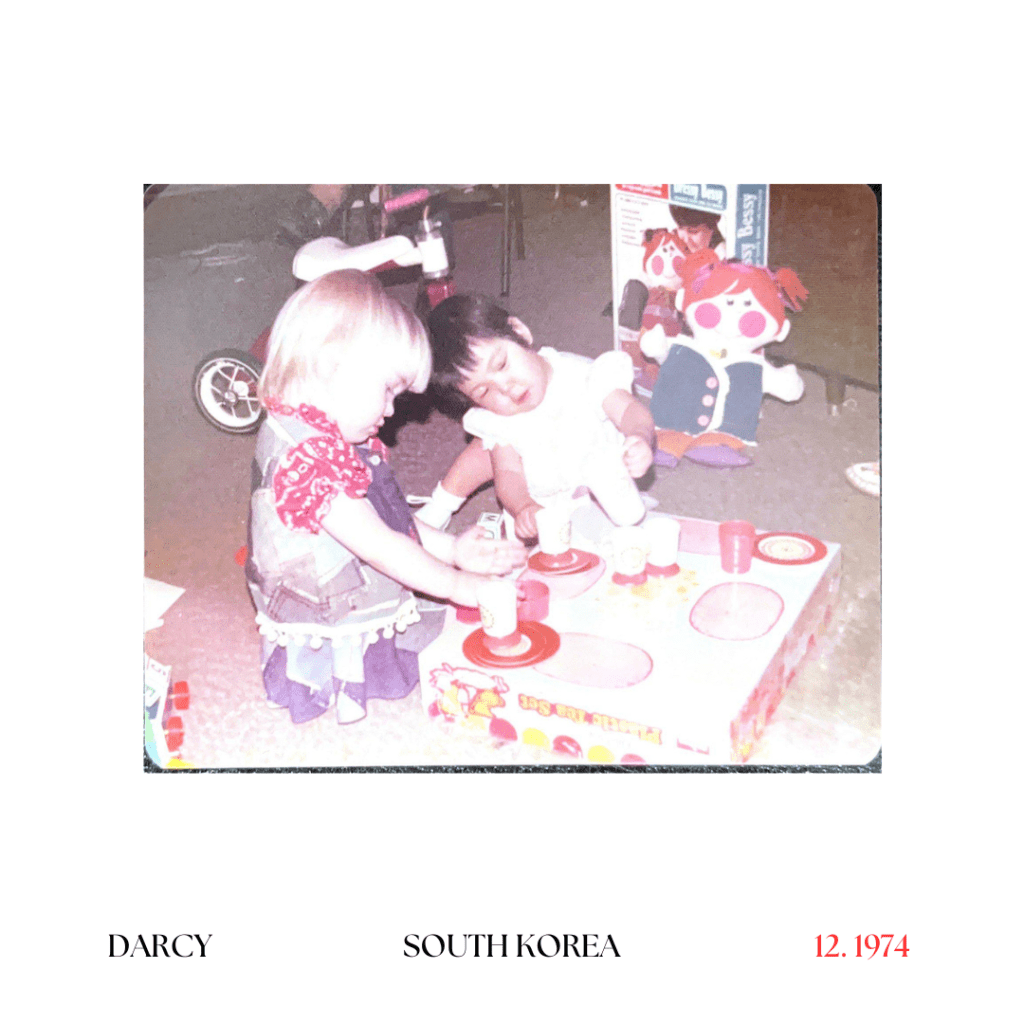

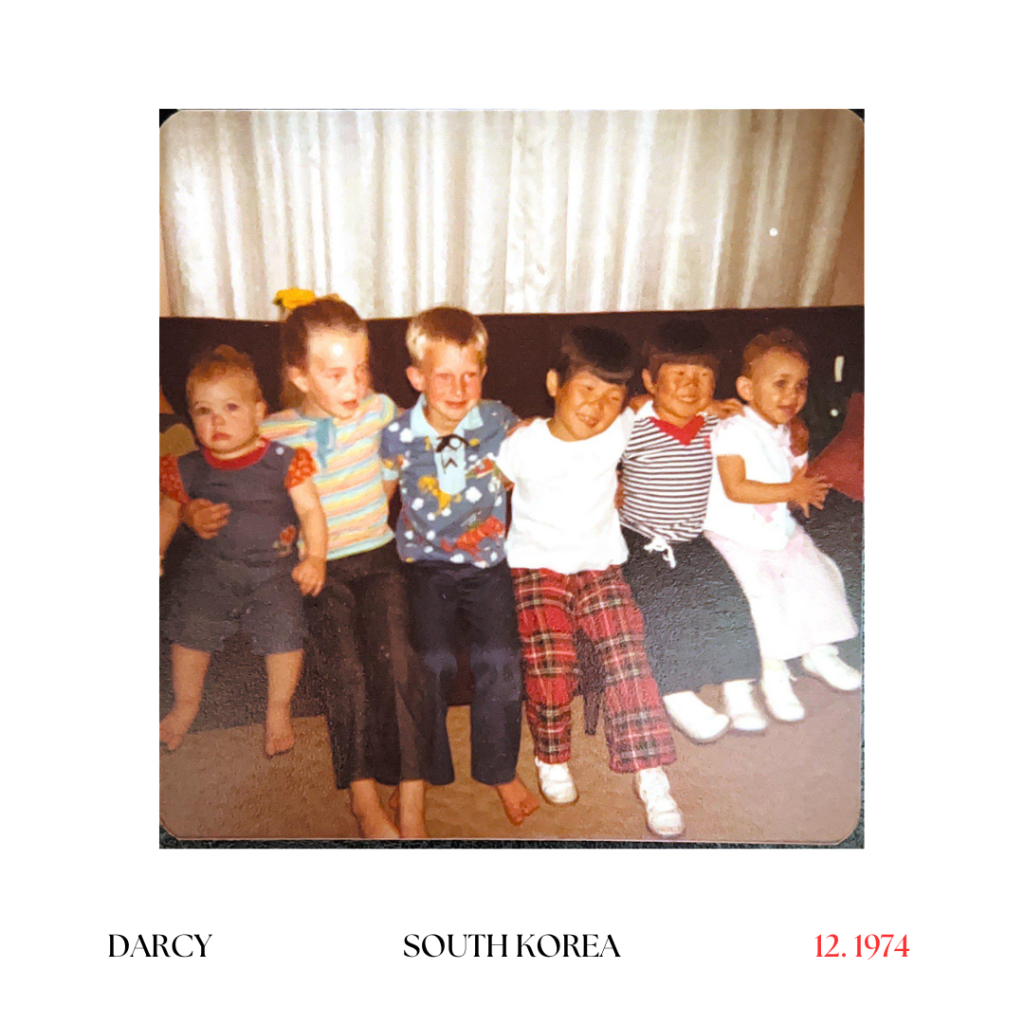

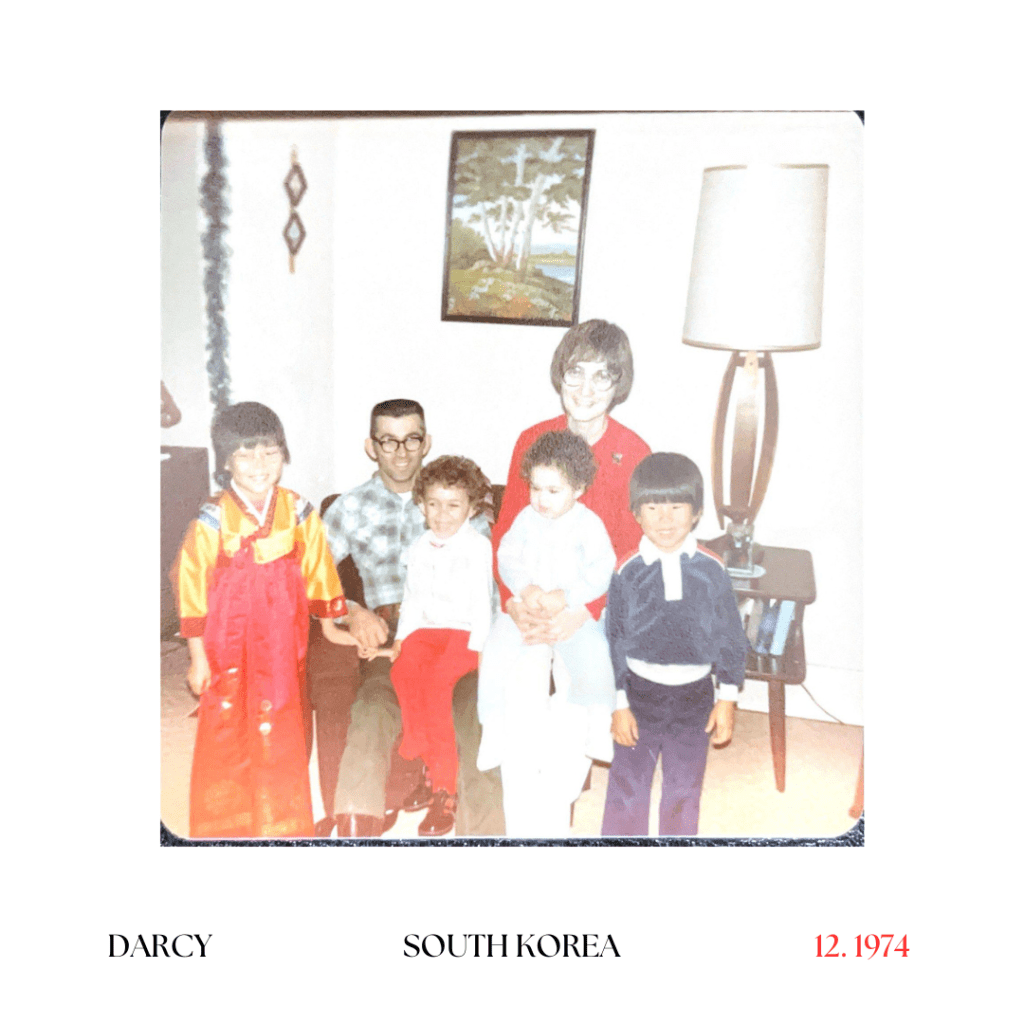

I was adopted into a white German-Danish family and am the oldest of three siblings. My brother is from Korea, and I’m from Korea, but not from the same bloodline but through the same agencies. My two sisters are biracial and were domestically adopted within the state of Nebraska.

So, it was interesting that my parents chose to adopt four different kids. However, growing up in that family, it seemed to me it was never appreciated that we were from different cultures or ethnic groups. We never celebrated any of our cultures or ethnic groups. We were never asked or allowed to talk about or ask questions about our heritage. We were never given any opportunity to learn about it outside of what was taught in school. Part of that not saying that it is totally my adoptive parents, is the location we grew up in. Having grown up in rural Nebraska, the Midwest does not have a lot of cultural camps. However, we could have traveled to Colorado, Minnesota, or Missouri.

The other strange thing that I learned later on in life is my parents never stayed in touch with our adoption agency, Dillon International, which I think could have helped in helping with the learning process and just being adopted.

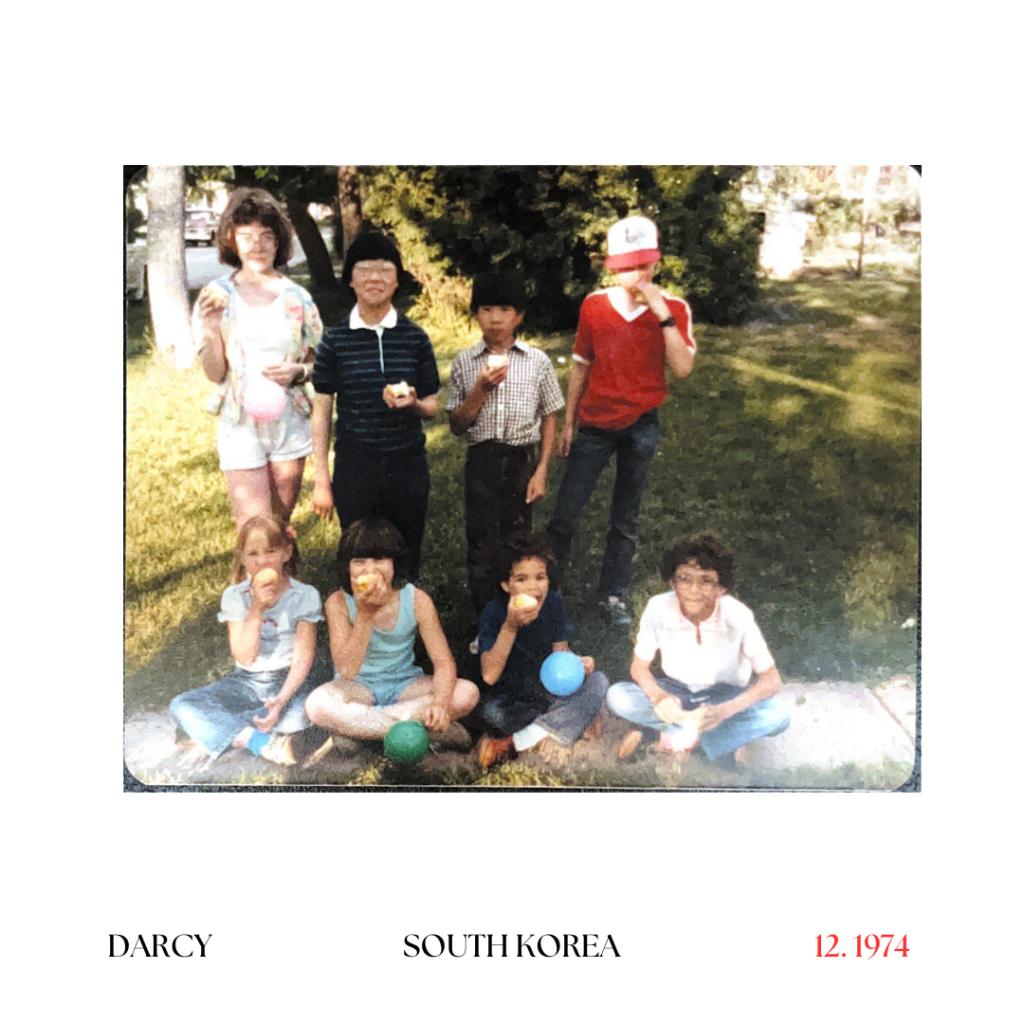

Growing up in the Midwest, of course, we were the only Asians around that I remember; my cousin was adopted from Korea, so that’s the only other one I knew. But like in schools or church or other activities, I don’t remember seeing Asian people, let alone even any other ethnic groups, until I got to college.

Growing up, I lived in a very dysfunctional home. My adoptive parents ended up divorcing when I was about 12 years old, and my youngest sister was about two. And so that left me to question why they adopted us if they can’t even keep the family unit together; there was a lot of fighting and abuse going on, a lot of dysfunctional behaviors.

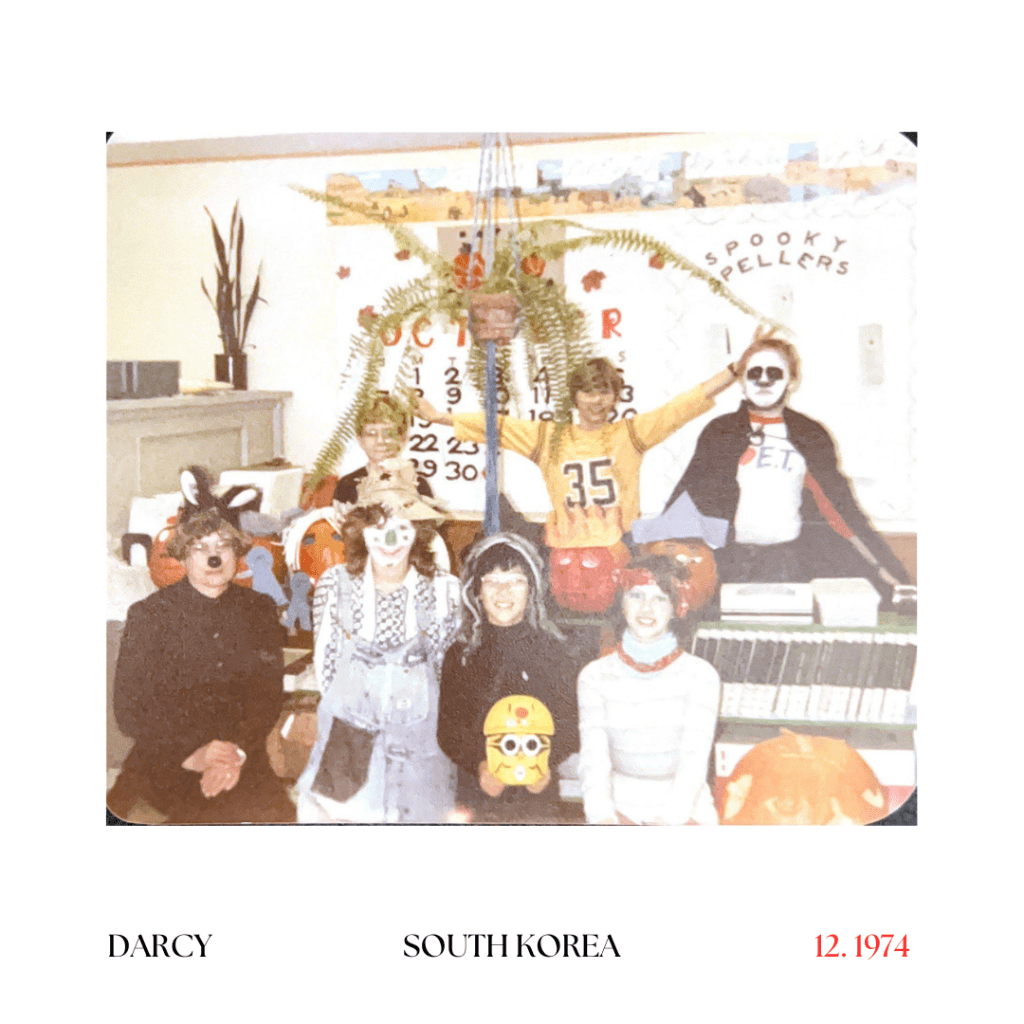

High school is where I think a lot of the tumultuous time for me in my adoption story came up. Now I wonder after looking back and reading the book Primal Wound and learning a lot more about adoption and adoptees, I was struggling a lot with my own identity because I’m Korean Asian, but also I was raised in a very dysfunctional, quiet, reserved, authoritarian household.

It was really hard to express anything or ask questions, anything about adoption or let alone life in general. So, I think that’s probably why I wasn’t aware that I was adopted until I got into high school and had to do an assignment in psychology class that looked at where I came from. You were supposed to ask your mom about her pregnancy story, but my mom was never pregnant.

So when I started asking questions like where I came from and why I was adopted, she refused to answer, and at that time, I was not in contact with my dad, so I couldn’t ask him. Jumping past high school into college, I then decided to open up the questions even more and try to ask again because I was taking psychology classes, which were my minor, and sociology was my major. I wanted to start questioning but again got shut down by both of my parents. My dad said one thing, and my mom said something different, so I never got clear answers as to why they had chosen to adopt.

In college, though, what led me to open up more about asking questions was another course I had to take in psychology. I thought, I’m in college; I can do whatever I want. So, I decided to do a search on my own. My two siblings, the youngest siblings, were adopted through Lutheran Families Social Services. So I decided to give them a call, and they told me you and your brother were not adopted through Lutheran Family Social Services; you were adopted through Dillon International, and I thought to myself, what is that? Where is that at? I had never heard of it. I looked it up and was set out of Tulsa, Oklahoma. How in the world did they find Dillon International? We had always lived in Nebraska. They had always lived in Nebraska.

In a long roundabout way, I called Dillon International and said who I was and what I wanted to do. And they were kind enough to fly me from Nebraska to Oklahoma one weekend, and I was able to stay with the cofounders of the agency Deniese and Jerry, and I learned so much about my adoption. It was impactful for me, but I had no clue. I didn’t know a lot of the stuff that they were sharing. It was breathtaking and awe-inspiring. I had no idea. I’m thinking to myself, why did my parents keep all this from me? What was their reasoning? I was studying and wondering if it was some form of jealousy or hurt. I have no idea.

But on the other hand, I was not happy; I was really upset that they kept it all from me. I’m not a person of big emotions because I was never taught to have emotions. So, it was hard for me to explain. As I was learning about my adoption, the agency felt terrible about what happened. They had agreed to help me go on the Birth Land tour 2001 to South Korea, which was so awesome.

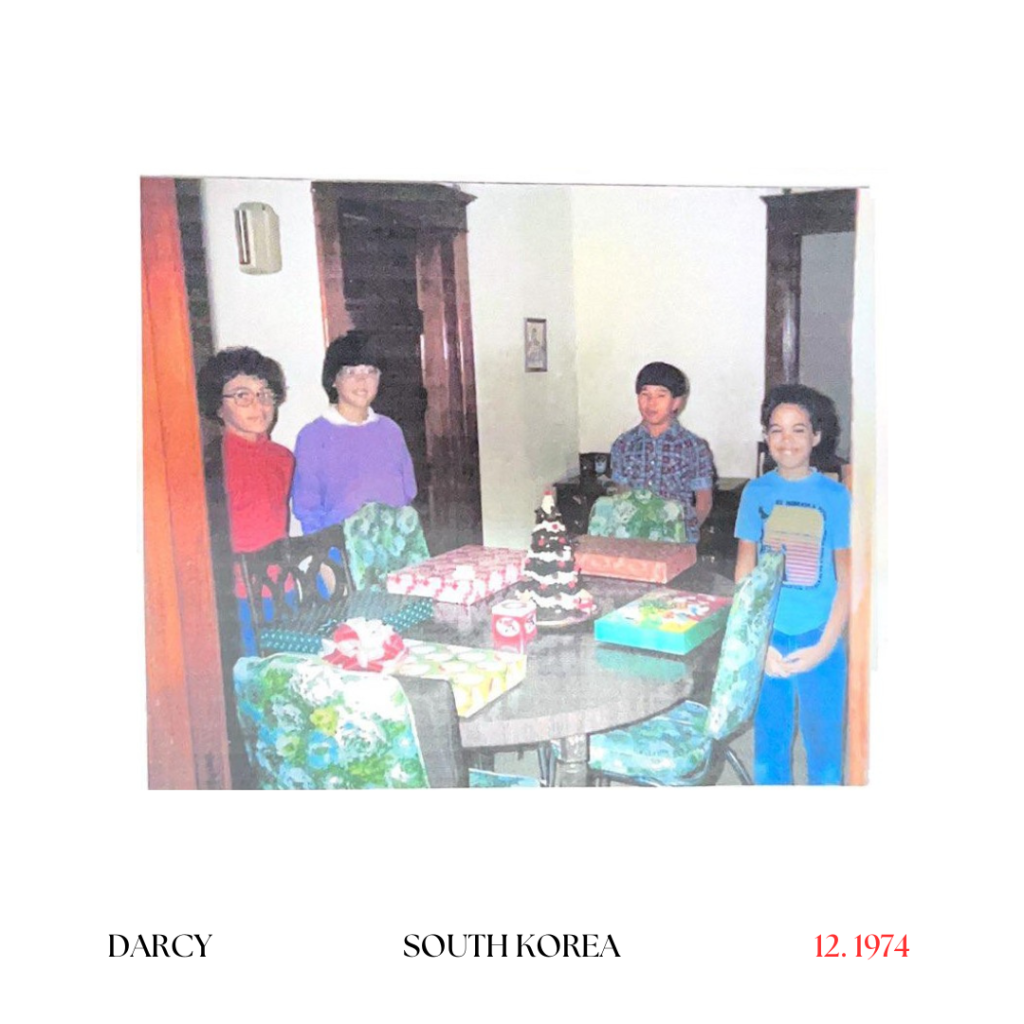

So, I got to travel with them to South Korea for the first time in 2001. By then, I was out of college and starting my life as a young adult. It was a whirlwind.

I don’t remember much about the trip other than looking at the buildings, the people around me, the food, the sights, and the smells. It was just really awesome.

Shortly after that, they invited me to come back and help with their Korean Heritage Camps and their Discovery Days, which was for teenagers. And so I had the opportunity to experience a couple of those, which again I’m like, why didn’t I have this growing up? I would have loved to have learned a little bit about my culture. It is so cool that young people can learn about the culture, experience the food, practice writing, and learn some dance. I never got to do that when I was young.

And then, with the teenagers getting into the deep questions of identity, who are you? What makes you tick as an adoptee and as a person growing up in your surroundings?

Then, in 2016, I had another opportunity to go back to Korea because, by that time, I was serving in the Lutheran Church as a youth director, and because I had been there for so long, they granted me a sabbatical. So I decided to go to Korea and do some searching around my roots, but before that, I had the opportunity with Dillon International. There was another agency in Arizona, where I ended up moving from Nebraska to Arizona in my young adult years. They had an agency called Dillon Southwest. I was invited to be on a panel of adoptees to talk to adoptive parents about what it was like being adopted and what tips I could give them to help them understand their adopted child. So that was kind of fun, and that’s how I got to know a little more about my heritage and adoption.

And then, in 2016, I got to go to Korea again for the second time with the adoption agency, and that one was a lot more meaningful because I was able to understand things a bit more and ask questions. I was a bit more emotional because there were other adoptees and their families going back and finding their birth parents and foster parents, and in one way, it was sad for me because they couldn’t find anything for me, but watching others, it was joyful to see them reunite.

I would say also with adoptees I didn’t know other adoptees until college. It was after college when I met other adoptees. I went to a small liberal arts college in Nebraska and I got a lot of mixed up with the foreign exchange student and had to correct a lot of people saying I’m not. So I’m going back to a lot of the issues that adoptees go through, microaggressions and racism and all that. I don’t remember a lot from my young years, but part of that is I don’t remember a lot generally because of the trauma. But in college, I remember a lot of microaggressions, and in young adulthood and my adult years, there’s been a lot of microaggressions and racism.

During the pandemic, I connected with many Korean Adoptees from all over the world because I was hungry to know more about my own adoption story and more about how they connect and everything. I took the time to research and search out webinars and Zoom meetings on Facebook. I found a Facebook group for people in the same orphanage I was in. So, during the pandemic, I connected with 15 other adoptees who were adopted from all over the world and had stayed in the same orphanage as me.

And now, in less than a month, I will be going back to Korea for the third time with some of my adoptee friends who were in the orphanage with me. So I’m very excited, and this tour is actually not tied to any birth land tour. We’re doing it on our own. I invited my social worker from the American agency, who happened to be a social worker at Eastern before she moved to the United States. She knows Korean very well and has always been our guide on the Birth Land tours because she speaks Korean.

We’re going to do three days of soul searching, go to the government offices, and visit the site of the orphanage—it’s no longer there, but we’re going to go where it was. We’re going to different adoption agencies, so Eastern, Holt, and KSS, where some of my other friends are from. Then we’re going to do DNA testing over there. And then we’ll do some sightseeing, and we’re really excited.

For a year and a half now, I have been facilitating an adoptive parent support group, which has been really cool. It started off by reading the book Primal Wound, and then they decided to stay as a group to talk with one another, learn from each other, and just share their joys and challenges about their adoptees and ask me questions. What did you experience? What do you recommend? So that’s really life-giving for me. And I’ve been trying to put together a young adult teen adoptee group and encourage adoptees to come together.

So, I’ve been much more involved in the adoptee community because of the pandemic and my general interest. That just gives me life, learning about adoption, learning about myself as an adoptee, and then learning how I can support either adoptive parents and or adoptees in their stories.

I am estranged from my adoptive family, and that is due to my own choice and is healthiest for me. But I would highly encourage adoptees who are really struggling with their families, and if there needs to be some moments or breaks to be estranged from them for a bit of a while that’s okay. And think about how to re-enter that healthily.

Now, I know that I am slowly getting back into a place where I can talk with some of my family, but I do it in a very cautious way and on my terms for my own health. I know that they haven’t changed—I’ve seen that and experienced it—they’re still as toxic as ever, but that’s just who they are. And I realize that’s who they are, but I have to set boundaries for myself.

I think when I was young and not knowing anything, I think my mom may have said that I was adopted, but I didn’t know what that meant. There were times that I felt like, and I don’t know if it was related to the trauma and abuse at home, but I just did not feel like I wanted to be adopted. Or was that more because I looked different and I didn’t want to be adopted? I wanted to be somebody else or look like somebody else. I don’t know. It could have been a little bit of both.

And then, throughout high school, I knew that I really wished I wasn’t adopted because I wanted to look like a white person. And I think in college and moving up into adulthood now, I don’t mind being adopted. I think it’s a great thing. The other piece of it is I believe adoption is not as much of a stigma anymore because back in the day, and I know a lot of adoptees, my adult group talks about how back in the day, parents felt like they had to save these kids, save the orphans. Let’s adopt to save the children. But now it seems to be out of love and wanting to have a child, and they really don’t care where the child comes from, and they just want a child.

But now, I think adoption is not a harsh word. Adoption is looked at as normal. It’s just another thing you do in life. So I feel fine. If I was married, I actually would want to adopt because I think adoption is a beautiful thing.

I have good things to say about adoption now as an adult, but maybe as a child and stuff that was different because of my circumstances.

So you’ve spoken about working with adoptive parents. What advice do you have for people looking to adopt?

It doesn’t matter if it’s domestic or international adoption; I highly recommend that the adoptive parents read the book Primal Wound by Nancy Verrier. For me, it unpacks the trauma and the unconscious trauma that an adoptee comes with, and the adoptee has no choice in it. They were separated from their birth mom, and it doesn’t matter what age, what stage, or whatever they were separated. There is automatically a primal wound that nobody can explain. I would highly recommend that book and that every adoptive parent is given that book from the agency so that they have an opportunity to open their eyes and learn about the scientific or the biological connections and the emotional implications of what adoptees are struggling with from the get-go and that might help the parent understand their child a bit better. It doesn’t answer all the questions, but it will give a little bit of a window into what the difference is between a child who a parent gets to keep right after and a child who has to be let go or adopted.

Two other things I recommend are getting into support groups for adoptive parents and finding other adoptive parents with whom to share their struggles, challenges, and joys.

But two, as the adoptee gets older, is to get them, especially if they’re multicultural, is getting them into courses and classes and camps to allow the adoptee to wonder and be curious about who they are, where they came from, and not to be ashamed of asking questions.

But I also know that some adoptees have no interest in these camps and not force it, so if a child doesn’t want to, that’s fine. But to always be open and let them be curious about their adoption, their records, and their stories.

Do you have any advice for other adoptees who have gone through similar experiences?

My number one piece of advice for adoptees is to get into a peer group find some other adoptees to be in and around to share your feelings because there is an unspoken connection when you are around other adoptees. We all just know there’s just something about us that we all just know. We connect in a way that is hard to explain, so I highly encourage adoptees to find other adoptees to be with and share the joys, challenges, and sorrows. And to be able to talk with one another and ask questions because you can say things without having to over-explain just automatically click.

The other thing I would highly recommend for adoptees is not to be ashamed of the need to go to therapy or to figure out you know who you are, psychologically, emotionally, spiritually, or whatever. Get the help you need.