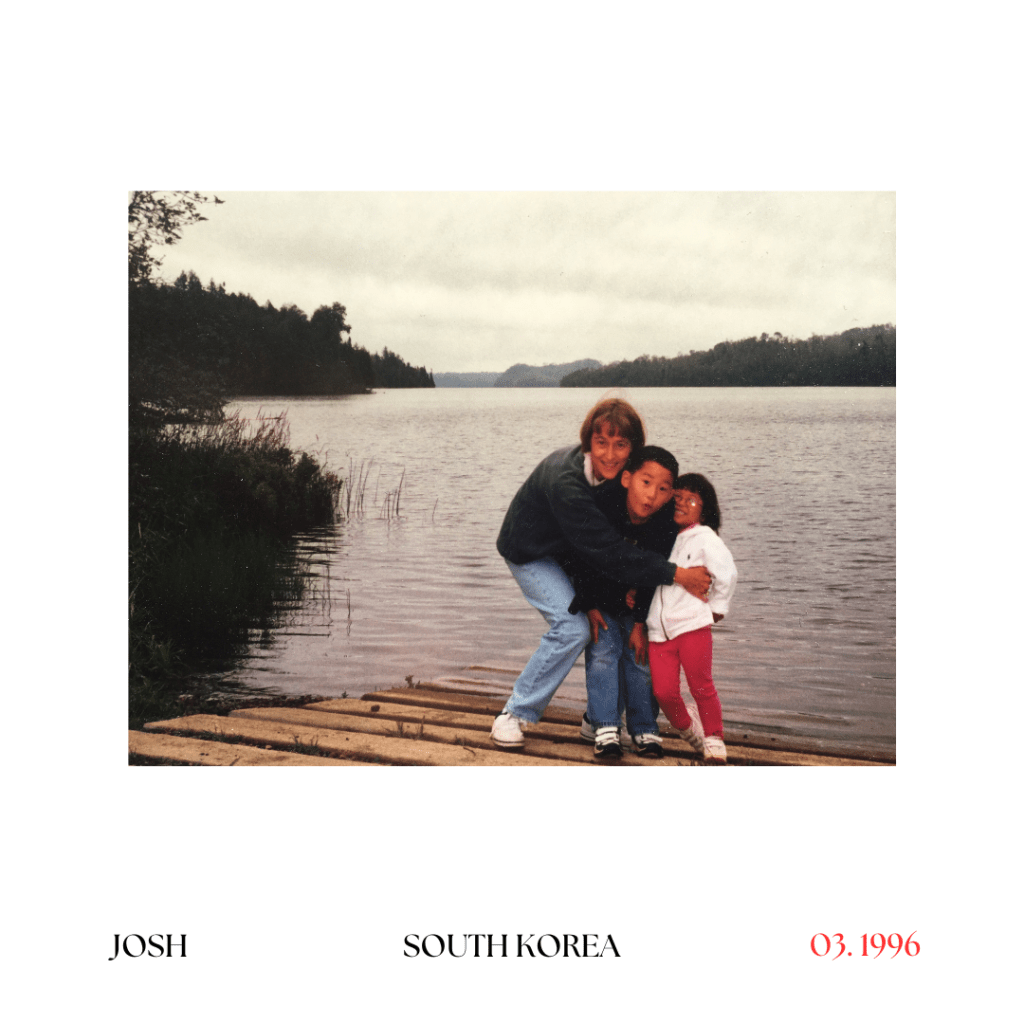

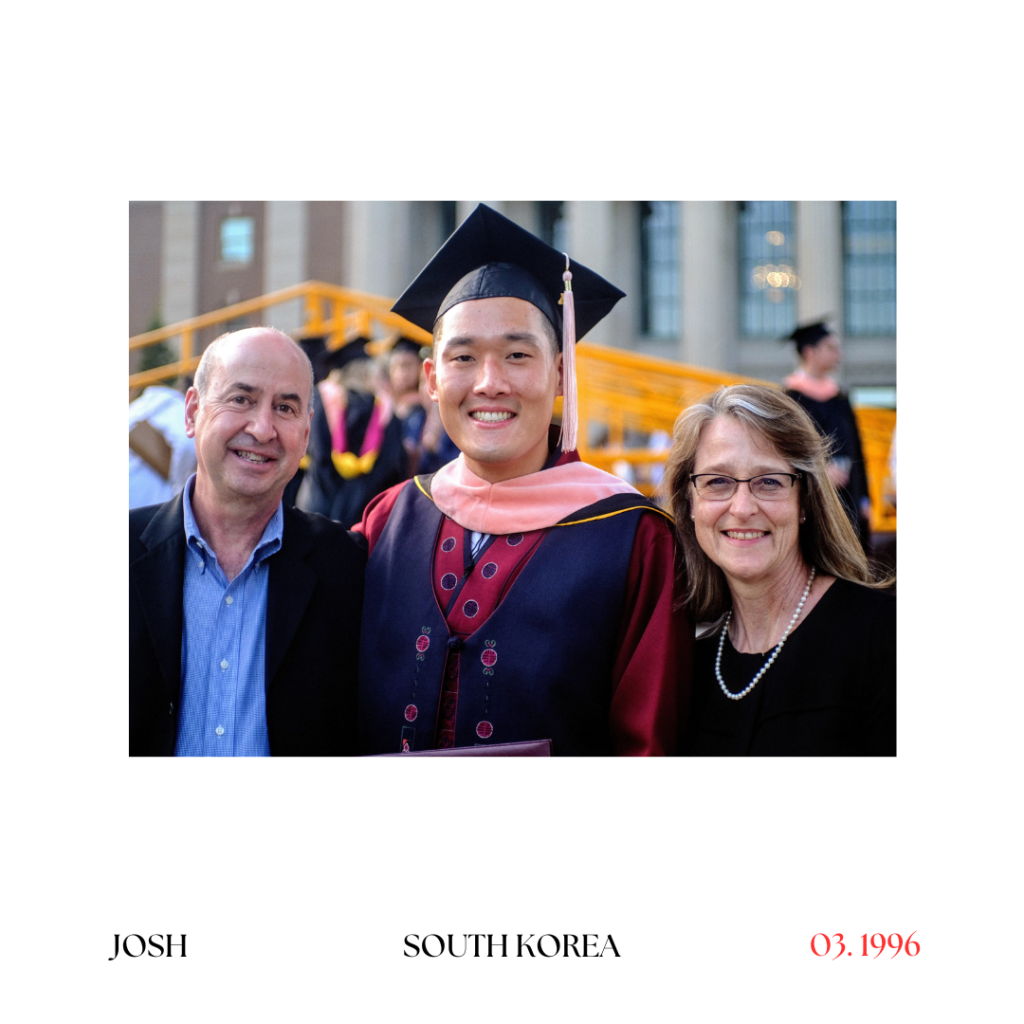

I grew up in Apple Valley, MN and I currently live in Queens, NY. I was adopted from Incheon, South Korea when I was around four months old.

I don’t think I had an aha like come to Jesus moment where I was like damn I’m adopted. I look different than my mom and my dad but, I didn’t have one of those moments where my parents told me. I never felt like I was white and I always just knew that and I think especially growing up in a predominantly white community, the otherness was just always brought to my attention whether I wanted it to be or not.

I didn’t give a whole lot of thought into adoption until it was late, not late adulthood, but late within the context of how old I am. So in the last 3-4 years. In elementary school, I remember my mom would come to my class once a year around my adoption day, and she would wear her hanbok (Korean Traditional Dress) and that she would bring Korean snacks and talk about South Korea and I would share my Korean name with the class which was kind of a humanizing moment, which is really cool and obviously kids just love free snacks that they don’t get to see at their grocery store a whole lot.

I feel like in my adoption journey just having that as a dedicated day up until middle school, not only humanized it, but I don’t wanna say it normalizes it because I don’t think adoption is quote unquote normal. Like you said, it’s often a last resort for family planning. It can tend to be a very sudden thing and not necessarily something that a prospective family thinks of from the forefront, but I think it makes having an Asian kid in your class with white parents who pick him up at school seem a little bit less weird.

Nicole: That’s really cool that you had that.

Josh: Yeah, I definitely sometimes I was super embarrassed about it at the moment, but now it’s like, that was really cool that she did that. And I mean you obviously don’t go into a whole lot of depth with elementary aged kids, but it was still a helpful thing for sure.

And then, Korean culture camp. I think that was another thing when growing up and even now, it’s cool to go and see kids and adults that look like you. And so especially as a kid, I think that was always consistently my favorite time of the year was the first week of August when we would go to camp and I could hang out with friends that I never got to see outside of camp and they all looked like me, and it was never weird, and I got to eat Korean food and Korean snacks.

But it was also bittersweet because from a very early age, I would get super bummed when camp would end because I was like, damn, I don’t get this more than five days out of the year. But then being able to continue with camp up until even last year when I taught, I think that’s been really crucial for my journey as well. But it’s nice to talk about with my peers, who are also going back to teach, and we can kind of reflect on it as we’ve gotten older and the variances on our experiences and the variances in our our environments that we grew up in and our relationships with adoption because it’s super different for everybody else.

And I think the coolest part for me has been seeing kids who are not adopted, but the children of people who were adopted and just how beautiful that is that these kids have a very real relationship with adoption because they’re parents are adopted or both their parents are adopted or whatever it is. And I feel like they have a really interesting relationship with it because it’s like my parent is adopted, but I’m not adopted, and that obviously is an important aspect of my parent’s identity.

And I think the last three years have been a kind of reckoning with adoption as an identity and questioning adoption as an institution. And I don’t know, I’m never gonna speak for all adoptees because we’re not a monolith, but I think I have a very, I don’t wanna say negative, but I am a bit more pessimistic towards adoption at least like transracially or internationally and how it’s affected me. I think the first like ah ha moment I may have had would be in 2021 with the mass shooting in Atlanta that killed all those salon workers who were Asian.

I saw a random Instagram post on the data about the shooting and it said, I’m paraphrasing here, but for transracial adoptees things like this can be hard for us to process because the perpetrators of the violence look like your family, but the victims look like you. And I was like, that’s so real but how do you reckon with that? When I walk out the door of my house everybody that I interact with who doesn’t know me at a very personal level just sees an Asian person or a Korean person and you know? They can love Korean people, but if you meet somebody who, hates, like truly hates Korean people or truly hates Asian people and to commit acts of violence I could be a victim of that because they don’t know that I was brought to this country against my will and raised in a family that’s white and a community that was predominantly white.

But then when I go home or I’m with my family, I see predominantly white people and that whiteness that I’ve grown up with has been baked into my epigenetic code and for a long time all I knew was whiteness growing up. I had white people food. I had Minnesota food. I wasn’t raised in a Korean family where we had Korean food all the time or things like that.

So I think that was a big aha moment where I was starting to question adoption as a system and had to search more within me and externally about my experiences and how that might be similar or different to other adoptees’ experiences. And then just going through therapy and life and kind of dedicating time and energy to learning more about what it means to be a transracial adoptee and how important it is to connect. Because nobody’s story is the same, you know, even if we were born in the same town and we were on the same flight to Minnesota and we grew up in the same neighborhood, you can have a very different outlook on adoption and a very different experience of adoption than I do. So I think it was more about connecting and communicating at this stage in my life with respect to adoption than it is just about discovering more.

Nicole: Yeah, I think you put that really nice. There’s different feelings that are associated with the different times. I think we went through a similar awakening, a lot of adoptees will call it ‘coming out of the fog’, and I think we want through that at about the same time because I feel so similar to you and you said now is not as much discovery as it is connection and that’s exactly how I feel and it’s important for me to, maintain the adoptee friendships that I have because even just chatting about day to day stuff is just validating in an unspoken manner.

Josh: For sure. For the majority of my life, from birth until definitely the end of undergraduate studies, I didn’t really care about adoption as it pertains to my personal identity. I knew it was a part of my identity and an integral part, but I never talked about it with other people that weren’t adopted. And I never even with other adoptees, never brought it up, if they brought it up I’d be like, oh, that’s cool, I’m also adopted. But I never really wanted to go on a birth family search. If I’m approached and it seems like it’ll be a fruitful experience, I’ll do it. Because for some adoptees that’s their finish line. I never felt like I needed to know if my birth family, my birth mother or whatever, whoever I might have contact with is alive. I just never felt like I wanted to do that. It was more so, if it happens, it happens and if it doesn’t happen then that’s okay to.

But then in the last three years, I’m still not super interested in the discovery portion. I’m not devoting a lot of energy to a birth search, but I want to be intentional about it. And I think I’m at a point where I just want to have community and connect with people. And if they’re comfortable sharing, talking about their discovery of their birth family, then I’ll feel equipped to do it on my own and do it sooner rather than later.

Yeah, random question to tie in the whole, chatting with other adoptees and lie the mundanity of our lives and how hyper specific that mundanity can be, at what point when you are dating somebody, do you tell them that you’re adopted?

Nicole: Ohh God, good question. Yeah, that’s a whole other topic, but I feel like I am the most comfortable with my identity as an adoptee, than I ever have been in my whole life. Right now because I’m in school, for this project, it comes out on the first date.

Josh: Yeah, because I feel like it has to happen that way because you tend to at least at some point in the day, talk about family. And it’s just so much easier for me to be like, OK, little prelude, a little preface before we dive into this, I’m adopted, and I feel like some people will get really uncomfy when you say that, Yeah, maybe not not uncomfy, but they don’t congratulate you.

Nicole: Really, I feel most people congratulate me and I think they’re trying to connect it to their life.

Josh: ‘I adopted a dog’

Nicole: Dude, that’s my favorite shit hahaha.

Josh: So you’re comparing me to your pet? That’s sick, thank you… But when it comes to dating, if family comes up and it’s my turn to share, I’m just like, yeah, I’m adopted. My parents are white, I have a sister who’s also adopted, not biological, because that’s always the follow up.

Can you talk a bit about your experience going back to Korea?

I was ten, so it’s been 17 years. I think this is going to be a non productive part of the interview because I honestly have started to forget a lot of things from that trip. But I remember pivotal moments on that trip. I remember we flew at a time when there was no direct flight to Korea. And so, it was the longest trip I’d ever been on. I flew from Minneapolis, Saint Paul to Tokyo and had a layover in Tokyo for a few hours. And then from Tokyo to Incheon, I remember the bus ride from the airport to our hotel in Seoul.

I remember the food the most. I remember the food we had at the hotel. There was a breakfast buffet and it was all kinds of Westernized food. But I remember that was the first time in my life that I was able to have kimchi for breakfast, white rice and kimchi for breakfast, which was like a peak moment for me.

I remember going to Eastern Social Welfare Society, which is the adoption agency that I was adopted out of. And I forget his name, but he was the leader of Eastern Social Welfare Society. And when you would go on these tours, he would meet with each family individually and have a private discussion and things like that.

Honestly I don’t remember a whole lot outside of that. I remember I did get to call my, it wasn’t my foster mom, but somebody who cared for me for a little bit in the orphanage. But that was also weird because I was ten, and so I didn’t really know what to say and she only spoke Korean. And it was so weird because it wasn’t me obviously because I was 10, but I think my parents wanted me to talk with them.

Children’s Home Society hosted it, and it was one of their workers that was trying to get in contact with them and they finally got in contact while we were doing something on the tour. And I was sitting on the coach bus alone with a translator and they would talk in Korean to the translator. And then the translator would translate it to me and then hand the phone to me. And I didn’t know what to say, but it was obviously this important thing.

Do you have any information about your birth or foster family?

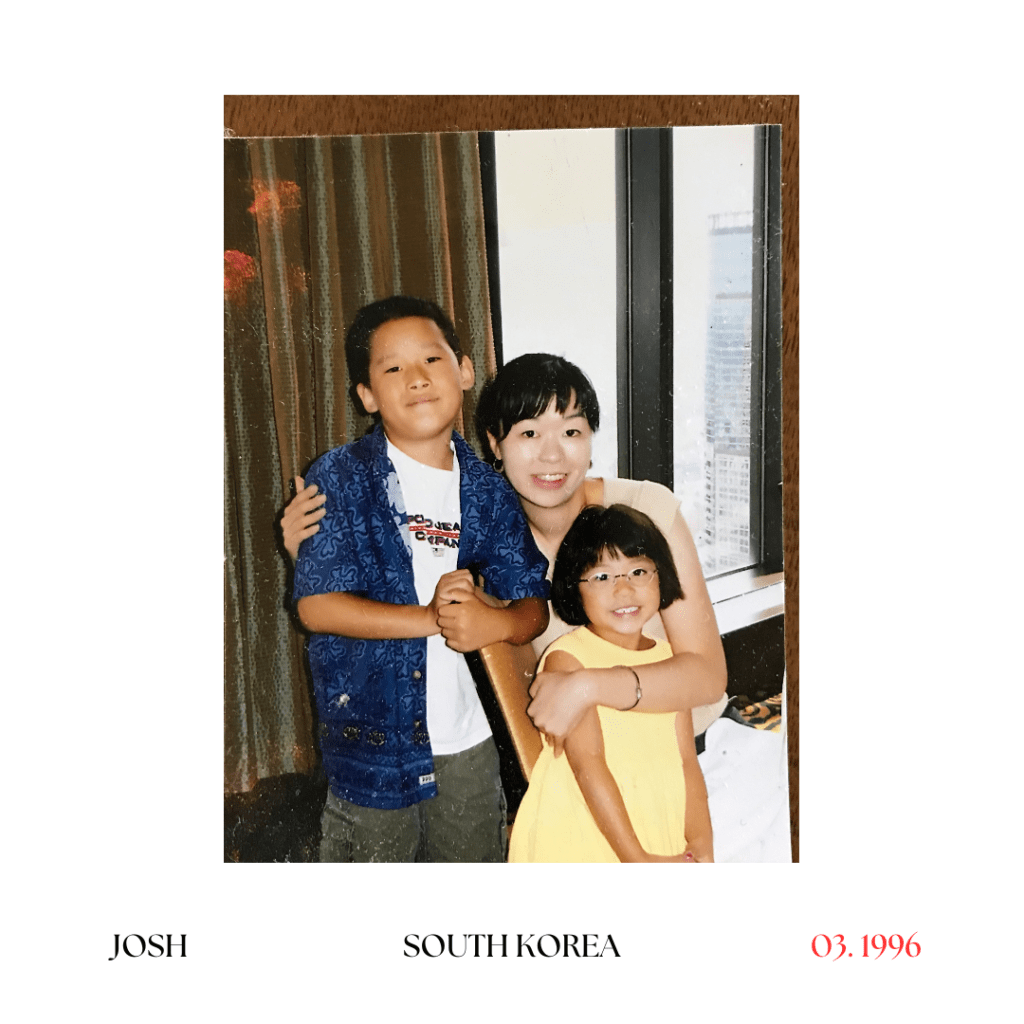

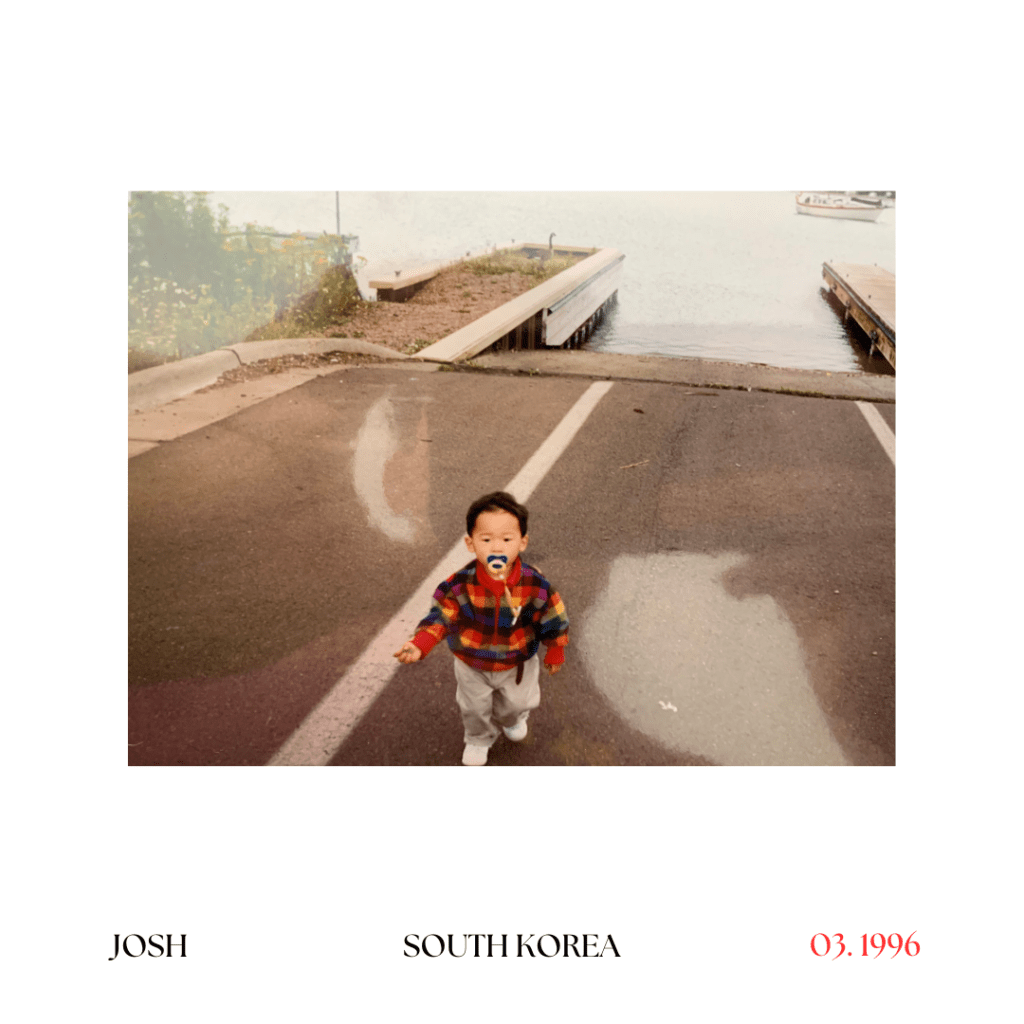

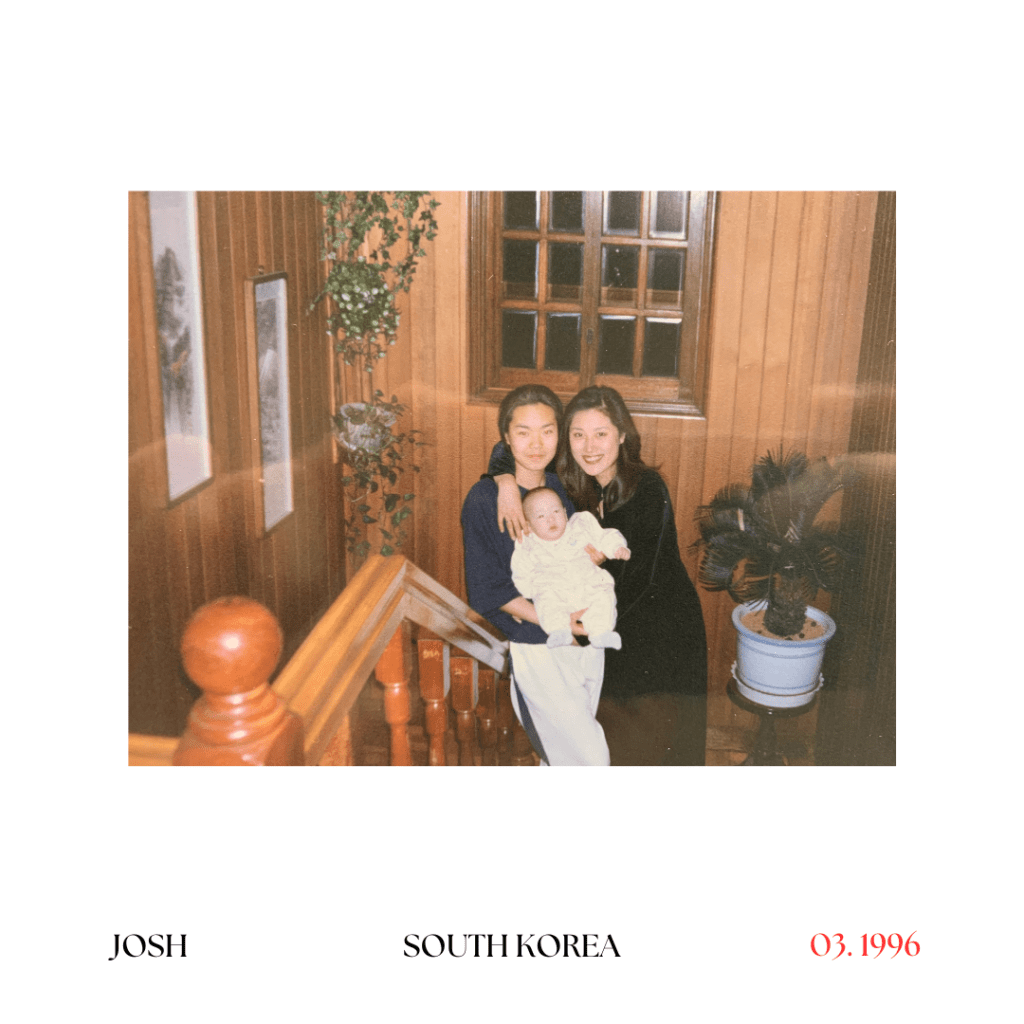

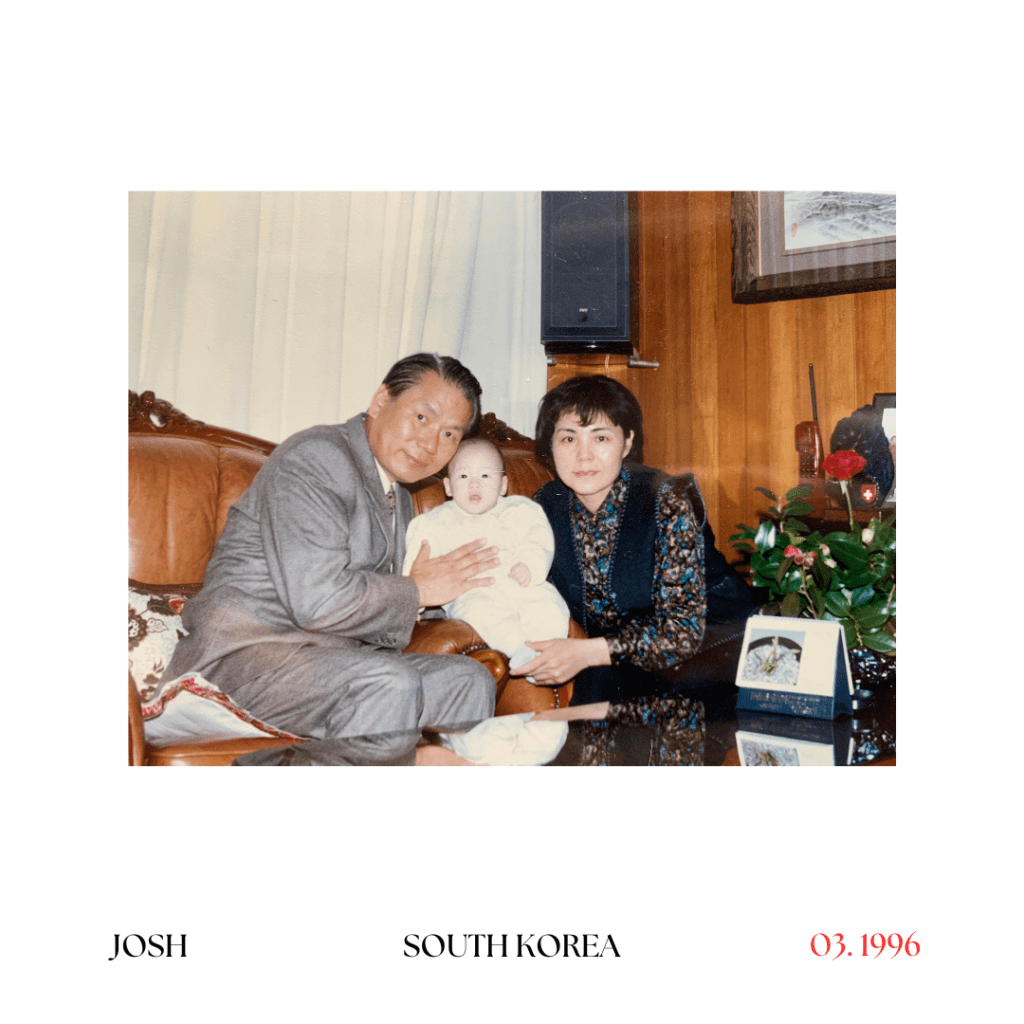

Two years ago I asked to see my adoption papers, So I know a few things from that. I feel like from what I’ve been told by other adoptees, I have a lot of information relative to some other people. I know my birth mother’s name. I don’t know my birth father’s name because he was not in the picture. My Korean name is Kim Jong Tek. She was 18. And that’s kind of all I knew from the papers or the foster family stuff. I don’t have a lot of written information, but we have a lot of photos. I had two foster sisters and a foster mom and dad. And I think they just took care of me for a short period of time. From what I know, I was a premature baby and also had pneumonia when I was born. So I was really sick and I think they cared for me while I was exiting the hospital before being flown out for adoption. We have a lot of photos from what I’m assuming is probably like a really brief moment of time. So that’s cool that I got those and my family has those. Some people that I’ve met don’t have any papers or like everything that I’ve been told could be totally false, which is super weird. It’s such a weird state to live in, like everything I’ve been told is just I gotta take it at face value.

Nicole: That’s another reason why I’m not going into more of the discovery mode either because I don’t know what I would do if that part of my story, even just the file stuff changed because that’s what I’ve known forever. Some people do 23andMe, and then they’re like, ohh yeah, I’m actually predominantly Japanese. I’ve invested in the Korean culture and I think I would be really devastated to find out something like that.

Josh: No, I’m similar. It’s like I really want to keep digging this hole of discovery, but what if I do find something that’s earth shatteringly different, okay, not to be dramatic, but I think ultimately it would be difficult to get over it or accept it. But that is such a heavy thing for an already really heavy thing like a piece of your identity, you know?

I think I have a very complicated relationship with it. I do recognize that adoption is for a significant proportion of people the only way or one of the most reliable ways to have a family and I would never wanna take that away from anybody. I think where my hiccups are with transracial and international adoption.

In a perfect world, you kind of alluded to local adoption or like native adoption would be the predominant way forward, but for a lot of countries, that’s not feasible. And in Korea, there’s the whole stigma around it. It’s not popular and I don’t know if it’ll ever be popular within Korea and so I think if adoption is to move forward internationally from any country there just needs to be a reform of how we approach it and the whole parent thing. I don’t know that it’s hard for me to like intellectualize the parent aspect to it because I’m not a parent, but if you’re a parent who’s adopting a child from a country that is not your country, and especially if they’re ethnicity and race, are different than the child’s, I think you need to be you need to work twice as hard as a parent. Like you need to understand that this child is going to go through their life with a very different relationship with race and ethnicity. There’s gonna be a whole lot of trauma around the unraveling of adoption and how it pertains to them. And so I would just want all parents to be open to talking about it. Just give your child the bandwidth and support them holistically, don’t force it if your kid seems like they don’t want to explore it as an option at that point in time. I don’t know, it’s so complicated. I don’t have a solution.

I think my perspective is like I think I alluded to, it definitely changed from going from very noncommittal, I don’t want anything to do with it or It’s not at the forefront of what I’m thinking about or the forefront of my identity, and that’s changed so that’s what I would say, I definitely I’ve come to like, accept it and embrace it and just come to almost enjoy being uncomfortable with it and talking about it with people.

Nicole: How would you say you identify them as an adoptee? Would you say you’re a Korean American adoptee, would you say you’re a Korean adoptee? Or do you not associate with it at all, you’re just like this is who I am. And that’s fine.

Josh: Yeah, that’s a hard question. I think if I’m filling out a census, I put Asian, and if there’s if they did the research and they specify and they break ethnicity down to East Asian and parentheses, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, etc. I think in a perfect world I would maybe put ‘other’ or if I could pick multiple because I tell people I’m a Korean adoptee.

I used to say Korean American, but now I say Korean Adoptee because I think when I would say Korean American people think I have Korean parents and that I was born here to Korean parents and now when I say Korean adoptee, I think it just alludes to I’m Korean, I was born in Korea, but I was raised here in America, so that’s what I say.

But with how I identify, I guess it also depends. I don’t know. I think it feels like a passing thing. But, if I’m not super comfortable with the person or if I’m never gonna see this person again, I’d maybe just say, a Korean American.

I think with food for me it’s a very sacred thing because cuisine is so specific to a country. And so for a tourist and you’re going somewhere, or if you’re trying to learn a new culture, I think food is such a specific way of understanding a culture and a people because you can look at it from so many different lenses, the flavor profiles, it all could be different, the ingredients they use. I think a perfect example is Korean Army Stew, it has a lot of quintessential Korean ingredients such as ramen and kimchi and all these other things. And it’s quintessential in Korean eating culture, to share with a group of people. And then when you dig deeper into the historical and social implications of Korean Army Stew, it was a dish born out of the post war economy and a lot of these leftover rations, and Korea was very poor at the time, and so people just made do with what they had.

I think that’s cool and I can use food as a way to not only understand more about my culture, but the history of it and how it changes and what dishes are popular in Korea or abroad, and what scene is more traditional and nontraditional. For me, food just makes sense. I would much rather read a cookbook or read a book, or read a recipe about Korean food and learn how to make it and learn how to perfect it and share it with people than I would want to break open a textbook and read a chapter on Korea. It’s also fun because then it’s like I either get to eat it or I get to share with people and eat with them.

I think the last thing I would say is just for me, I don’t think the journey will ever end, it’s just this lifelong thing. I’m just eager to go back to Korea too, I really wanna go back and spend a month or two there. I think that would just be, really not even to just do the discovery things, but just to go back to the homeland. So, I hope I get to do that soon.

Do you have any advice for adoptees that have gone through similar experiences to you?

I would say be curious again, it’s a lifelong thing. Be patient, you don’t have to figure it all out in one sitting or one year or one trip to Korea. And I think it’s uncomfortable to have conversations with other adoptees, or other people who aren’t adopted or other people who are adopted from different countries.

It’s been really cool to meet people who are adopted from different countries because again, it’s totally different. The genesis of adoption and their country could be totally different from Korea. It’s a community. And I think it can be really scary to talk about that stuff, but from what I found is whenever I find out somebody’s adopted from Korea, it’s like an instant bonding moment, even if it’s kind of uncomfortable at the start because, dropping the the adoption bomb is not something I do frequently with people I don’t know because it is super uncomfy. But if you find somebody who’s adopted from Korea, just try to make a connection, it could fizzle out, could be like a one and done thing like, oh, that was cool, nice to meet you. Or it could be this lifelong thing that you connect with them year after year after year like us. We were in high school and it’s like 12 years later still talking, that’s crazy. I can’t say I’ve done the same with every other person I met at camp, but there’s a few people I still remain in contact with and it’s good.